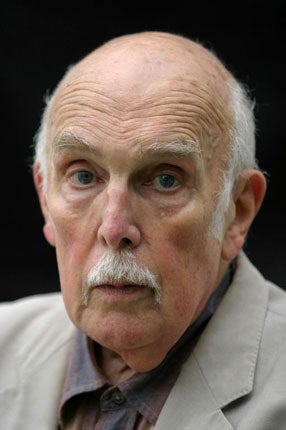

Sir Bernard Crick: Political theorist and Orwell biographer who advised the Government on citizenship teaching in schools

Bernard Crick was an academic who wrote two books which were international bestsellers and received critical acclaim. In Defence of Politics (1962) went through several editions, was translated into five languages and sold over 400,000 copies. For years it has been required reading for students. Nearly 20 years later he wrote the authoritative, if not official, George Orwell: A Life (1980). Crick generously attributed the warm reviews to his subject – "it's the man".

Crick was born in London in 1929. When he left Whitgift School, Croydon in 1947 he opted to read Economics at University College, London, rather than at the London School of Economics. He later claimed that he would have read History at Oxford, if he had passed O-level Latin. In his third year of study he switched to Government and spent more time at the LSE. The break came when his Economics tutor gave him a high mark for an essay on value theory, but correctly divined that Crick did not believe in the subject.

LSE was a remarkable constellation of talent at the time. Karl Popper, Lionel Robbins, H.L. Beales and Harold Laski dominated the social sciences. On the strength of attending some lectures by the fading Laski, Crick – always on the left – saw himself as a child of the great man. His quick, even quirky brain, formidable memory and fluent writing encouraged him to register for a PhD. Over two years he did not make much progress on the topic, the scope and method of political science.

As a pacifist he did not want to do National Service. A four-year sojourn in North America provided a way out. Spells at Harvard and Berkeley enabled him to complete his thesis. It was published as The American Science of Politics in 1959. At the time behaviouralism promised to make the subject more scientific. Crick dismissed not only the scientific pretensions but showed how value-laden much of it was. The book is now regarded as a classic.

In 1957 Crick was appointed to a lectureship at the LSE. He became part of a department, divided between the followers of Laski (who died in 1950) and his conservative successor, Michael Oakeshott, for whom Crick was something of an enfant terrible. He publicly dismissed what he considered Oakeshott's arid political philosophy; Oakeshott famously regarded the task of politics as "keeping afloat". Crick's Reform of Parliament (1964) reflected his reformist outlook. Crick wanted a professorial chair to stand not sit on.

In 1965 he was appointed Professor of Political Theory and Political Institutions at Sheffield University, and many at LSE breathed a sigh of relief. He could not help but enliven the department and made a life-long connection with a mature student, David Blunkett. His writings moved easily between the study of political institutions and political ideas. But his intellectual roots and home were in the metropolis. He had trumpeted his move from London in the New Statesman and urged others to follow his path. But his move was half-hearted. To the disapproval of university authorities he would stay overnight with colleagues or even camp in his office.

Commuting took its toll and in 1971 he moved to a Chair in Politics and Sociology at Birkbeck College, London, which specialised in teaching part-time and mature students. He remained there until 1984 when he took early retirement. He was only 54 and this was the ludicrous outcome of savage government cuts in higher education. In 1982 he had disappointed his friends by seeking the vacant Gladstone chair in Public Administration at Oxford, whose syllabus and style he had often castigated. Crick and All Souls would have been an unlikely combination.

In these years Bernard Crick extended himself too much and, he would admit, too thinly. At Sheffield a major project on toleration, supported by the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust, foundered. Crick's independence at times made him bite the hand that fed him. He had a long spell (1966-80) as joint editor of Political Quarterly and was later literary editor. Its contents bridged the divide between academe and public life. He was chief examiner for Government and Politics at A-level for London University and transformed the stale "British Constitution" into a lively syllabus. He was on many quangos, study groups and a prolific writer for The Observer, The Guardian and New Statesman. No centre-left gathering was complete without him. His Political Quarterly essays and editorials on the current political scene, and large number of edited books and theatre reviews all seemed to come easily.

He also devoted himself to a campaign to advance political literacy in schools. It was fitting that in 1997 David Blunkett, then Education and Employment Secretary, appointed him to chair an advisory group to report on ways "to strengthen education and citizenship". His report led in 2002 to the establishment of compulsory citizenship classes for all pupils in secondary schools. Some years earlier he and Blunkett had authored a statement of Labour's aims and values.

But friends expected more of such a brilliant man. Where was the big politics book? Crick thought that his activities were those of a public intellectual, in the honourable tradition of G.D.H. Cole and Laski, and reflected his concern for integrating political theory and political practice. He had no particular expertise to offer a practical politician apart from what he considered to be his good judgement.

Crick made a distinct niche in the universities he served. He was a good head of department but his extra-curricular activities and globe-trotting cut back on his availability for wider university duties. ("Sorry I'm not here on that day or the day after"). He was matey with students and encouraged genuine researchers. His off-the-cuff lectures were educative but also at times self-indulgent. Brighter students appreciated the asides – mischievous, indiscreet, brilliant and only sometimes relevant. Less sophisticated students found them difficult to follow as he argued with himself.

He mastered a severe stammer and, and as a young student, had cherished the encouragement from a fellow sufferer – Nye Bevan. In seminars Crick could be a menace if he was not the centre of attention. Over time his face would redden, his bald head shine, as he grimaced, rolled his eyes and snorted and muttered. He would burst in with a refutation and a suggestion that they should be talking about something else.

In the 1980s he became part of the George Orwell industry following the publication of his biography in 1980. The ascetic Orwell and hedonistic Crick were an odd combination. But both were essentially essayists; in an article published six months ago, Crick praised the form of the essay: "it leaves the reader in some uncertainty about what is going to be said next, and it can create the feeling of listening to a well-stocked mind observing or arguing not to win a point but for sheer pleasure". And both were on the side of the underdog and, though on the left, were never disciples. Like Orwell Crick thought that a writer should take sides but not be a "loyal member of a party".

He was knighted in 2002 "for services to citizenship in schools and to political studies". He wanted more and suspected that a nomination for a peerage had been blocked. There was something incongruous about him being one of the Good and the Great. He was a good choice to chair the panel for the 2003 Orwell Prize for political journalism and political writing. He looked for some preferment under Harold Wilson and Neil Kinnock – in vain. Labour and university leaders found Crick a niggler, a "yes but" man, neither old nor new Labour.

Crick loved argument, regarded politics as the essence of a free society and thought that one was impossible without the other. Technocracy, consensus and managerialism were all anti-political. He was happy to describe himself as polemicist.

He eventually became an honorary Scot based in Edinburgh. Having campaigned vigorously against Margaret Thatcher's elective dictatorship, he was alarmed at the authoritarianism in New Labour. He was a strong advocate of PR, devolution and any measures that helped political pluralism. He wrote a fine book in 1991 on national identities.

Crick had a huge appetite for life, arguing, drinking, and hill walking. His charm and wit made him seductive to many women. Because he was a character, and so original, people were always interested in what he had to say; if they disagreed with it they would dismiss it – "it's only Bernard". When he was 70 and recovering from an operation, a friend (who wrote obituaries) wrote to ask after his health. Crick's terse reply was to ask why the friend wanted to know "and if you say 'can't say', well I'm in good health". In later years he wrote generous and perceptive obituaries, including a laudatory one of his old bête noire, Oakeshott.

Dennis Kavanagh

Most biographers enjoy fairly short-term relationships with their subjects, writes D.J. Taylor. Bernard Crick's association with George Orwell, on the other hand, lasted for the best part of three and a half decades. Having negotiated the immensely tricky obstacle of Orwell's widow, Sonia, to produce his ground-breaking George Orwell: A Life (1980), which all subsequent Orwell biographers have taken as their starting point, he then devoted himself to a series of projects intended to perpetuate Orwell's legacy.

Most of these took place under the auspices of the George Orwell Memorial Trust, which he founded in 1980, the contribution from his own hardback royalties being matched by David Astor, Orwell's son, Richard Blair, and the three papers to which Orwell had been most consistently attached, The Observer, the Manchester Evening News and Tribune. The Trust began by continuing an existing scheme of Crick's to fund projects by writers whose work Orwell might have been expected to approve, before changing track in the mid-1980s to establish annual lectures in his memory at Birkbeck and Sheffield University.

Then in 1993 came the most imaginative scheme of all – the founding, with sponsorship from Political Quarterly, of two annual awards for journalism and literature. From humble beginnings, and a modest budget, the Orwell Prizes have in recent years developed into one of the highlights of the UK publishing calendar, a process in which Crick himself was intimately involved. In the midst of an exacting professional regime, he worked tirelessly on the Trust's behalf, zealously recruiting new blood, drumming up support for the prizes and shamelessly soliciting favours from the highly placed friends in whom his address book abounded.

His most striking characteristic, when hot on the Orwell trail, was his disinterestedness. Grand academic eminences very often turn chilly in the face of upstart competition: Crick, by contrast, was a notable supporter of younger scholars and critics, always on hand with encouraging letters and appreciative reviews. Orwell studies is forever in his debt.

Bernard Crick, political scientist: born London 16 December 1929; Assistant Lecturer in Politics, then Lecturer, then Senior Lecturer, London School of Economics 1957-65; Professor of Political Theory and Institutions, Sheffield University 1965-71; Joint Editor, Political Quarterly 1966-80, Literary Editor 1993-2000; Professor of Politics and Sociology, Birkbeck College, London University 1971-84 (Emeritus); Chairman, Committee on Teaching Citizenship in English Schools 1997-98; Kt 2002; three times married, firstly 1953 Joyce Morgan (two sons; marriage dissolved 1980); died Edinburgh 19 December 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments