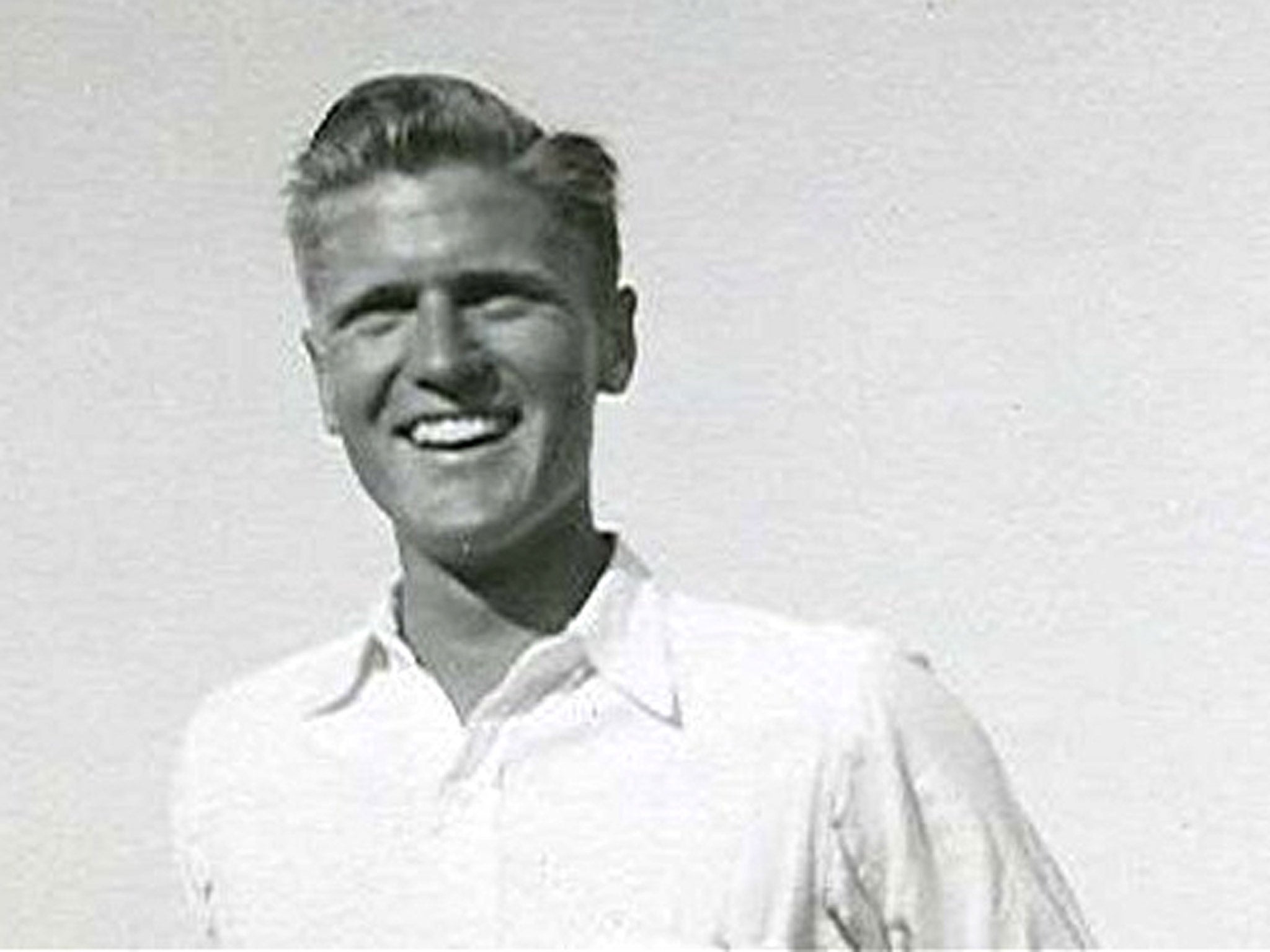

Tennent Bagley: CIA agent at the heart of the controversial defection of Yuri Nosenko who came to believe the Russian was a plant

One day in June 1962, Tennent "Pete" Bagley, the Soviet specialist at the CIA station in Berne, was instructed to take the train to Geneva to handle the case of a KGB officer attached to the Soviet delegation to a disarmament conference, who was offering his services to the Americans. That short journey turned Bagley into a central figure in perhaps the most controversial and baffling spy story of the entire Cold War.

The KGB officer's name was Yuri Nosenko. At that first meeting he agreed to return to Moscow as a CIA agent-in-place. But in January 1964 he was back in Geneva with the Soviet arms delegates, insisting his cover was about to be blown and that he had to come over to the West. But was he the real thing, or a fake defector sent by the KGB to confuse? If he was a plant, the strategy succeeded brilliantly. For the next dozen years the Nosenko case tied the CIA in knots, paralysing the Agency's vital espionage efforts against its Cold War adversary and destroying careers in the process.

Bagley's background was typical in the Agency's early days. He came from an old US Navy family, studded with admirals; his uncle had been the first American killed in the 1898 Spanish-American war. Bagley himself had served in the Marines and studied at Princeton and the University of Geneva before joining the CIA in 1950.

He seemed to have it all. He was tall and all-American handsome, talented and ambitious. Some senior figures in the Agency saw him as a future CIA director. He was also a friend of James Angleton, the Agency's formidable counter-intelligence chief. And then Yuri Nosenko came on the scene.

Initially Bagley had no doubts. Nosenko was the first senior defector from the KGB's Second Directorate, responsible for internal security and monitoring – and if possible recruiting – personnel in the US Embassy as well as visiting American tourists, businessmen and academics. The information he provided at the 1962 debriefings at a CIA safe house in Geneva was top-class, including details of KGB surveillance methods and leads that hastened the unmasking of several Soviet spies in the West (among them the UK Admiralty clerk, John Vassall).

"Jim, I'm involved in the greatest defector case ever," Bagley enthused to Angleton when he returned to Washington. But the older man was visibly unimpressed, and handed Bagley a file to read. "When you finish this, you'll see what I'm saying," he told him. The file essentially consisted of the theorising of a previous KGB defector, Anatoly Golitsyn, who had come across in 1961.

Golitsyn had managed to convince the paranoid Angleton that not only did the KGB have high-level moles in US and British intelligence, but was running a gigantic disinformation campaign against the West. Nothing was what it seemed, and every defector, according to Golitsyn, was in fact a plant – among them, naturally, Yuri Nosenko.

The file planted doubts in Bagley's mind too, and his suspicions were further aroused by discrepancies in Nosenko's initial story. In 1964 those doubts exploded. The defector claimed to have information that the Soviet Union had nothing to do with the murder of President Kennedy just two months earlier and, astonishingly, that the KGB didn't even have contact with Lee Harvey Oswald, Kennedy's assassin, during the three mysterious years that the one-time US Marine lived in the Soviet Union, between 1959 and 1962.

Nosenko's tale seemed too good to be true, exonerating Moscow just as the Warren Commission was starting work amid widespread suspicion that Oswald was indeed a real-life Manchurian Candidate controlled by the KGB. Soon after landing on US soil, Nosenko found himself a prisoner, held incommunicado in a safe house in Virginia and subjected to harsh interrogation, hunger and sleep deprivation.

But he never broke, passing lie detector tests and resisting every effort of Bagley and his fellow sceptics to extract a confession. Gradually the upper echelons of the CIA split into warring camps, of "Fundamentalists" like Angleton and Bagley, and those who believed Nosenko was the real thing, and who were increasingly appalled by the way he was being treated. Ultimately the latter group prevailed. By 1967 Nosenko's ordeal was over, and in 1969 he was formally cleared, placed on the CIA payroll as a consultant and given a new identity.

By then Bagley was long since off the case, posted to Brussels, where he would spend five years as station chief before retiring from the Agency in 1972. Amazingly Nosenko never held his harsh treatment against the US, nor regretted his original decision to defect. Bagley, though, remained obsessed by the case, convinced until the end that Nosenko was a plant: "this KGB provocateur and deceiver," as he put it in his 2007 memoir Spy Wars, a powerful argument of the anti-Nosenko case.

The book led the CIA to cancel a planned lecture that Bagley was to give: four decades on, old wounds were still bleeding. Nosenko himself died in 2008. A few years earlier, someone asked Bagley what he'd say to Yuri Nosenko if he ever ran into him. His answer was, "Don't shoot."

RUPERT CORNWELL

Tennent Harrington Bagley, CIA officer: born Annapolis, Maryland 11 November 1925; married 1955 Maria Lonyay (one son, two daughters); died Brussels 20 February 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments