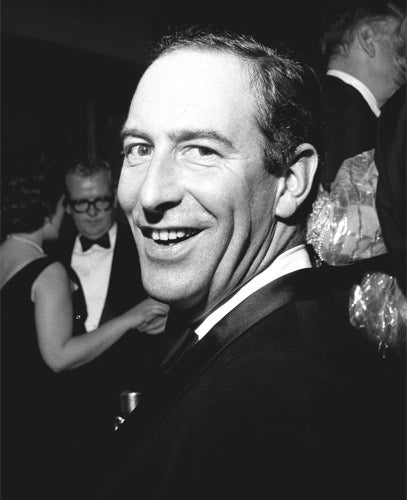

Thomas Hoving: Maverick museum director who transformed the Met in New York

In the public imagination, museum directors should be donnish and discreet, impeccably tasteful and thoroughly proper. That wasn't quite how Thomas Hoving saw the job.

To do it, he once said, you needed not just patience and scholarship, but also the attributes of a "gunslinger, ward heeler, legal fixer, accomplice smuggler, anarchist and toady." And he should know. For 10 tumultuous years he ran the Metropolitan Museum of Art, arguably New York's flagship cultural institution. When he left, the Met and every other major museum around the world would never be quite the same.

Hoving was an unapologetic show-man and hustler, of boundless energy and an unceasing craving for attention. When he took the Met's helm in 1967, he was the youngest director in its history. In his interview as one of 40 candidates for the post, he told the museum's trustees to their face that their august institution was 'moribund, grey and dying." Not for much longer.

Hoving swept like a gale through the Met's fusty corridors. He enlarged its collections, adding galleries for Islamic, African and Pacific art and, horror, brash contemporary art as well. He had banners draped outside to advertise popular attractions, and to promote the blockbuster special exhibitions that he largely pioneered but which are now staples of museums around the world. The Met became more popular, more trendy and – its crustier aficionados would certainly say – distinctly more vulgar.

Never did those traits combine more effectively than in the Treasures of Tutankhamun show of 1978. Hoving by then had left the Met, but he was the moving spirit behind an exhibition that was the climax of his endeavours. In four months, 1.3m people came to see it, bringing an extra $100m of tourism revenue to the city. "King Tut" also sealed the emergence of the museum store as a shopping destination in its own right, another innovation for which Hoving was largely responsible.

Despite the showbiz flash, his academic credentials for the job were impressive. The son of Walter Hoving, a retailing executive who became chairman of Tiffany and Co., Thomas was educated at Princeton, where he graduated summa cum laude before taking a masters and then a doctorate in art history.

In 1959 he became an assistant curator at the Cloisters, the section of the Met dealing with the European Middle Ages. There, he pulled off an early coup, helping the museum acquire the Bury St Edmonds Cross. In his 1981 book The King of the Confessors he recounted his quest across Europe for the 12th century masterpiece made of walrus ivory. His lust to acquire it overcame all shame. "I am being devoured by this cross. I want it, I need it," he once pleaded with a dealer who knew of its whereabouts.

In 1965 Hoving's career took an unexpected detour, when John Lindsay, the incoming Mayor of New York and a personal friend, asked him to become the city's parks commissioner. He brought his trademark brio to that job too, closing off Central Park to traffic on Sundays and instigating zany events known as "Hoving's Happenings".

But in 1966 James Rorimer, the Met's director, died unexpectedly, and at the age of only 35 Hoving was chosen to succeed him. Hyperactive as ever, and never taking no as an answer, he travelled the world ceaselessly, cultivating contacts and making acquisitions, the more headline-catching the better. In 1971 the Met bought Velasquez's portrait of his slave "Juan de Pareja" for $5.5m, then a record price at auction. The following year, in a venture that did not end so happily, the museum paid $1m for the exquisite, 2,500-year old Euphronios vase.

It later transpired that the vase had been looted from an Etruscan tomb, and in 2006 the Met was forced to return it to Italy. Hoving later conceded that from the outset he had doubts about the provenance of the vase, which he referred to as "the hot pot." But at least he was honest about the bare -knuckles competition behind the suave and velvety façade of high art. "If you don't work yourself up into a fever of greed and covetousness in an art museum," he wrote later, "you're just not doing your job."

In 1977 Hoving resigned as director to set up a new communications and media centre at the Met. But that project collapsed and – perhaps inevitably for a man who once joked his middle initials stood for "Publicity Forever" – he entered the media full-time.

For six years he was a cultural correspondent for ABC television, and between 1981 and 1991 edited the now defunct Connoisseur magazine. There the poacher turned gamekeeper, chiding the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles for its take-no-prisoners acquisition tactics, so reminiscent of Hoving's own. He also produced a rollicking 1993 book about his days at the Met, entitled Making the Mummies Dance.

Towards the end though, a note of introspection and self doubt on occasion intruded. "I should have done something else," he wrote in The Artful Tom, his most recent memoir. "I should have forced myself to be less aggressive, less selfish, less solipsistic, less feisty... My heavily-cleverly disguised low self-regard manifested itself in my constant showing off, my addiction for publicity and my intolerable 'me-me-me' attitudes."

If he had followed that advice the museum world might have been more decorous – but also a lot less fun.

Rupert Cornwell

Thomas Pearsall Field Hoving, museum director: born New York City 15 January 1931; New York City Parks Commissioner 1965-66; Director, Metropolitan Museum of Art 1967-77; married 1953 Nancy Bell (one daughter); died New York City 10 December 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks