Thomas M. Disch: Poet and writer of death-haunted science fiction who won plaudits for 'Camp Concentration'

The death of the American writer Thomas M. Disch, by his own hand, on the Fourth of July, was the last act of a drama that had been unfolding in public for several years.

As the author of a large number of death-haunted science-fiction novels and stories, and of several Gothic tales which treat modern America as a land of the dead, and of a huge body of poetry much of which danced with death in formal measure, Disch could from the first have been described as a writer well versed in terminus. But the personal disasters he suffered in the 21st century, to which he gave permanent shape in the many poems he published on his LiveJournal after 2005, raised this dialogue with death to a new intensity; to put an end to his life, as he spoke frequently of doing, was to cap that life in his own way, and to demonstrate that he really had meant what he had been saying over the 45 years of his prolific career.

From the publication of his first poems and stories in 1962, the central theme that could be discerned throughout this work was a passionate conviction that the desolateness of the human condition could only be "figured" through art, it did not much matter what (although Disch was a seriously bad painter). What was important was to make sense of the bad deal we had been handed as a species – one of his many volumes of poetry is entitled The Right Way to Figure Plumbing (1972). To figure things right, for Disch, was to treat death as a game, deadly of course, but beauteous. For Disch, in the end, death was only sensible if you did it yourself. These intuitions, certainly bleak enough, were articulated in a tone of almost unearthly high spirits: wry, mellifluous, formally exact, wickedly intimate, camp, deadly serious, surreal, unrelenting.

A science-fiction novel like Camp Concentration (1968), or one of the hundreds of stories like "The Asian Shore" (1970), or a children's fable like The Brave Little Toaster (1986), which became a Disney animated feature, or any of the thousands of poems (published under the name Tom Disch), or the critical essays in The Nation and elsewhere, or the opera librettos: anything he wrote was instantly identifiable. Perhaps one of the reasons he never achieved the very wide fame his readers assumed from the first he might be heir to was that the Disch voice took no prisoners: it was a voice you agreed with, or it dismissed you.

Thomas Michael Disch was born in Des Moines, Iowa, just before the Second World War, and was raised Catholic in Minnesota. His father was a door-to-door salesman; he became close to his four siblings (who survive him) only after he left Minneapolis for New York. He had volunteered for military service in his late teens, but was soon given a medical discharge. In Manhattan he attended but did not graduate from Cooper Union and New York University, where I first met him. As soon as he sold his first story, to the perceptive science-fiction editor Cele Goldsmith, he became freelance, and supported himself almost solely through his writing from that point on.

Along with Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin and Roger Zelazny, Disch was soon thought of as representing a new hope for science fiction; in the hands of these writers, the genre might finally be recognised for shaping valid responses to the world, rather than just as escapist entertainment. But by the time Disch published his first novel, The Genocides (1965), in which Earth is harvested by aliens totally indifferent to the fact that their actions are exterminating the human race – he had already begun to wander, ending up in 1965 in London, where Michael Moorcock's New Worlds was beginning to agitate for adult, modernist, unforgivingly experimental speculative fiction.

Disch's response was partial: Camp Concentration, first published in New Worlds and still his most famous novel, describes, in an intense iteration of his already unmistakable voice, a concentration camp run by the American military which is subjecting its inmates to fatal doses of a drug designed to increase intelligence. The echoes of Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus (1947) are clear and deliberate. The novel won some plaudits but no honours from the science-fiction community, which from the first could not tolerate Disch's corrosive disdain for the technocentric uplift typical of "normal" science fiction, and for anything that seemed to him to pander to the immaturity of most genre fiction.

Later, in the first of his critical studies of science fiction, The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: how science fiction conquered the world (1998), he deepened the insult by arguing that the genre was actually a form of children's literature. Oddly perhaps, the only awards Disch ever received from the community – a Hugo Award and a Locus Award – were given for this assault. A second study, On SF (2005), is similarly ruthless.

By 1970, Disch had returned to Manhattan, where he lived with his partner, Charles Naylor. He had been publishing poetry very widely, and in the 1970s there were many readers of Tom Disch who knew nothing of the prose writer. His poetry is technically conservative though often formally daring; his subject matter runs from public poems (an uncommon focus) to the confessional; the wit is always evident, and the voice, and the drumbeat of death; he is perhaps one of the very best second-rank poets of the later 20th century in America.

Meanwhile, he published, in 334 (1972), a formally demanding but ultimately extremely moving portrait of non-heroic life in a desolate near-future New York (334 is the number of an apartment block). And in On Wings of Song (1979), he published what has come to be recognised as his best single novel: it depicts the life of an earnest but unsuccessful artist in an even less habitable New York; the interplay here between a life dedicated to art (even mediocre art) and the unstoppable degradation of America into a land raddled by starvation (spiritual and physical) and malls, is utterly melancholy, but hilarious, too.

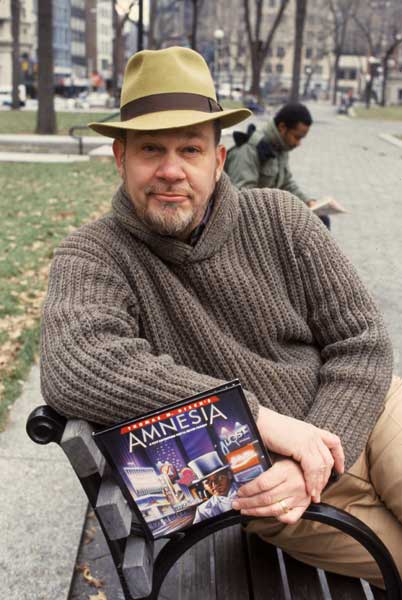

The next decade or so saw no falling off in quantity or quality, though the unresponsiveness of the science-fiction world inclined Disch to explore other modes. He had already written – under the name Leonie Hargrave – a Gothic novel, Clara Reeve (1975); he began the "Supernatural Minnesota" sequence of thematically connected metaphysical horror tales with The Businessman (1984), the most savage of the four, and The Priest: a Gothic romance (1994), a devastating satire upon Minnesota culture in which Catholic priests abduct pregnant teenagers and kill them. He also began to publish art, poetry and theatre criticism, much of which was assembled in The Castle of Indolence (1995) and The Castle of Perseverance: job opportunities in contemporary poetry (2002). He also designed a computer game called Amnesia (1986).

During these years, he grew into himself physically, both in mass, as he became heavy, but also in gravitas, as his presence became formidable. Tall and bald, he would bear down, colossus-like, upon his visitor, and though his voice was flute-high, he spoke in passages of such pith and wry sapience that a seminar seemed in the offing. But almost always this would change into hilarity. To him everything that humans did about things that mattered – from God to sex, from the Pope to the sestina – was ultimately silly. The heart of Tom Disch in person, gossiping profoundly about the world and its makings, was glee.

But the shades – he would have excoriated any use of that term, unless it also referred to ghosts – were drawing in. He had published dozens of books, but felt, it may be wrongly, that his publishers were losing interest. In the early 2000s, the flat he and Naylor had occupied since the 1970s was almost destroyed by a fire that spread from the apartment below, and his library was very severely damaged. His health began to decline. Naylor died in 2005 after a long and difficult illness. Within weeks of his death, eviction proceedings were begun against Disch; although the first notice was thrown out of court, the landlord soon tried again, in an action still pending at the time of Disch's death. The country house where he spent part of the year was destroyed by mould. The diabetes and sciatica and other disabilities intensified.

All these matters, via the LiveJournal, became in themselves a form of theatre. At the same time, Disch published The Word of God; or, Holy Writ rewritten (2008), a thoroughly wicked jape on God, religion, America, the figure of the artist, and not least himself (in this tale he denies, "unconvincingly", the rumour that he is Thomas Mann's illegitimate son: Mann was in fact a visitor to Minneapolis in the summer of 1939). At least five more books are in production.

Late this spring, however, Disch made it clear that the flood of poetry was beginning to ebb, and that, after nearly half a century of ceaseless fertility, his voice was drying up. This final loss, he made sure we understood, would not be tolerated.

John Clute

Thomas Michael Disch, poet and writer: born Des Moines, Iowa 2 February 1940; died New York 4 July 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks