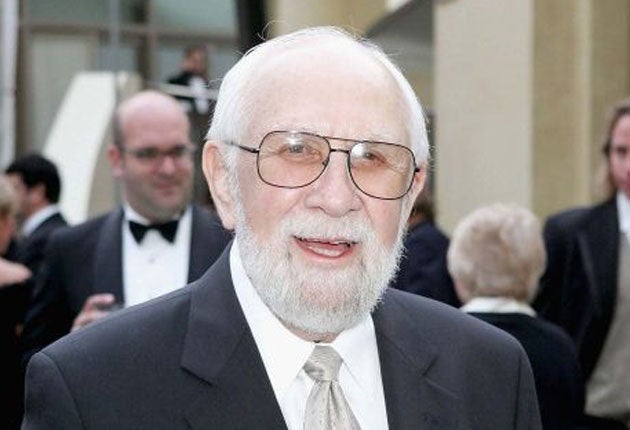

William A Fraker: Celebrated cinematographer who shot Steve McQueen's famous car chase in 'Bullitt'

William A Fraker was one of Hollywood's most admired and respected cameramen, contributing to such films as Close Encounters of the Third Kind and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, earning six Oscar nominations and winning three Bafta awards. Two of his finest achievements were released in the same year, 1968: Roman Polanski's chilling tale of witches in Manhattan, Rosemary's Baby, for which Fraker evoked an appropriately moody, threateningly enclosed and dreamlike atmosphere; and Peter Yates's Bullitt, with its bright, dusty location footage of San Francisco, and what is acknowledged as one of the most spectacular car-chase sequences put on film, for which Fraker famously had himself strapped to the front of a Mustang, holding a camera aloft as the vehicle travelled at more than 100mph, thus achieving thrilling point-of-view shots as the car careered up and down the city's hilly streets.

The following year, Fraker filmed the musical Western Paint Your Wagon, and star Lee Marvin was so entranced by his work that he insisted he direct his next starring vehicle, Monte Walsh (1970). In 2000 he received a lifetime achievement award from the American Society of Cinematographers, and its president, Michael Goi, commented on Fraker's death, "He embodied not only the consummate artistry that was necessary to become a legend in his craft, but also the romance and glamour of making movies."

Fraker was born in 1923 in Los Angeles, where his father and uncle both worked as still photographers within the studio system, as had his maternal grandmother, who taught his father photography. His uncle Charles ran the Paramount stills department until after the Second World War, when studios phased out such departments, and his father worked at Universal, Pathé, First National and Columbia before dying in 1934.

During the Second World War, Fraker served in the Coast Guard then took advantage of the GI Bill to study at the film school of the University of Southern California. The film department was run by Slavko Vorkapich, who had pioneered the use of montage in such 1930s MGM films as The Good Earth and San Francisco.

After graduating in 1950, he worked as a stills photographer, then as an assistant editor, assistant cameraman and camera operator on features, television and commercials. He was a camera assistant on the television series Private Secretary (1953), starring Ann Sothern, and The Lone Ranger (1956), and spent seven years on the popular sitcom series The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, rising during that time from second assistant to camera operator with the support of director-star, Ozzie Nelson. "If there's any success I have achieved or will achieve," he later said, "I attribute the major portion of it to Ozzie."

As camera operator, he started an association with fellow USC alumnus Conrad Hall on such series as Stoney Burke and The Outer Limits, and he was camera operator for Hall on the cinema features Father Goose, Morituri (both 1964) and The Professionals (1965) prior to gaining his first assignment as director of photography on the television series Daktari (1966). This led to his photographing his first feature film, Curtis Harrington's weird thriller, Games, in 1967. He then shot The Fox, The President's Analyst and Fade-In (all 1967), becoming noted for pushing boundaries, using faster and wider lenses, restricting lighting sources and employing a technique of deliberate over-exposure.

His sterling contributions to Rosemary's Baby and Bullitt demonstrated his diversity: the first was a largely interior, claustrophobic work; the other an action-packed thriller mainly set in brightly lit exteriors. Both films were among the biggest hits of the year. For the groundbreaking car chase in Bullitt, which set a Mustang Fastback against a Dodge Charger, director Yates, star Steve McQueen and Fraker decided to shoot the sequence at high speeds (with McQueen himself behind the wheel) rather than undercrank the cameras. Fraker later said, "Our idea was to take the audience on that trip, which really worked beautifully. The first time I saw it with an audience, they applauded at the end of the chase. It was absolutely sensational!" Fraker's friend, the actor-director Floyd Mutrux, said, "They went so fast his white beard flew up on his face. He couldn't see where he was coming from or going, but he got the shot."

Given a chance by Marvin (who had first worked with him on The Professionals) to direct Monte Walsh, he turned out a fine, wistful Western which touchingly explored the process of ageing and the passing of traditions, with Marvin excellent as a determined cowhand with a lust for life and a persistent optimism. "As long as there's one cowboy minding one cow, it ain't dead," he declares of his way of life, and he obviously intends to be that one cowboy. It is a sombre film, photographed (by David M Walsh) in washed-out colours appropriate to the mood, and Fraker gives Marvin some fine supporting players in off-beat roles – Jack Palance gives an atypical, understated portrayal of Walsh's pal, who refuses to cling on to the past, leaving the range for marriage and store-keeping, while Jeanne Moreau is superb as Walsh's tubercular mistress, who refuses to marry him because of her limited life expectancy.

"I love Westerns," said Fraker, "because that period is one of the most romantic times in history." Except for one bold sequence that does not come off – the filming of a bar brawl entirely in close-up – Fraker's direction was otherwise lauded, with his eye for imagery readily apparent. Though admired by those who saw it, Monte Walsh was too downbeat to be a major hit – Walsh ends the film a solitary figure, talking to his horse for company. Fraker directed two more films, A Reflection of Fear (1973) and The Legend of the Lone Ranger (1981), both inconsequential, though he directed occasional television episodes for series such as Wiseguy and Walker – Texas Ranger.

The 1970s are regarded as a period of change and experimentation with film photography, and Fraker was part of a group that included Vilmos Zsigmond, Nestor Almendros and Laszlo Kovacs, all of whom had risen through the studio system to become influential masters of their trade. But Fraker also maintained a love for the old studio lighting, and he was given the chance to recreate the style when he was cinematographer on Warren Beatty's Heaven Can Wait (1977), for which he won his second Oscar nomination – his first was for Richard Brooks's Looking for Mr Goodbar (1977), with its daringly dominant use of darkness, frequently leaving only eyes visible in the gloom.

Fraker also gained Academy Award nominations for Steven Spielberg's 1941 (1978), for which he received two, for cinematography and for visual effects, John Badham's WarGames (1982) and Martin Ritt's Murphy's Romance (1985).

Fraker was director of photography on over 50 films, and shot additional footage for Milos Forman's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), and extra scenes for Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1976). When Burt Reynolds, who had starred in Fade-In, made his directorial debut with Gator (1976), he asked Fraker to be his cinematographer. A personal favourite of his films was American Hot Wax (1978), loosely based on the career of the disc jockey Alan Freed, because he had an intense fascination with the early days of rock'n'roll.

Fraker, who had a personal tragedy when his son, William A Fraker Jr, also a cameraman, died at the age of 32, was an enormously popular figure, noted for his larger-than-life conviviality, his calm temperament, and for the help he extended to young camera operators. For the last few years of his life, he taught at USC and he gave his last class in May, always emphasising that the look of a film should be determined by the film itself. "I don't agree with a cinematographer putting his stamp on a picture," he said, "or wanting to recreate reality. The only reason to attend a concert, a stage play or a movie is to escape reality. You have to be a story-teller, to invite the audience into what you want to say and take them on a trip. Part of that is photography, so why should I make it look 'real'?"

William A Fraker, cinematographer and director: born Los Angeles 29 September 1923; married (one son, deceased); died Los Angeles 31 May 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments