Yolanda Sonnabend: One of the finest stage designers, who worked with Sir Kenneth Macmillan at the Royal Ballet

She was also a painter of note and the National Portrait Gallery holds her portraits of subjects as varied as Stephen Hawking, Steven Berkoff, and Joseph Needham

Yolanda Sonnabend “was one of the truly great theatre designers of the 20th century,” said Deborah MacMillan, whose husband, Sir Kenneth MacMillan, was a close collaborator with Sonnabend at the Royal Ballet for 30 years. Sonnabend also worked with Anthony Dowell and created the Fabergé-inspired costume designs for his 1987 Swan Lake – which, he said, “broke the traditional mould and took the ballet visually to new heights. In my opinion, her designs made the production totally unique.”

Her Royal Ballet début in 1963 was making the costume and set designs for MacMillan's Symphony, and other important designs included Natalia Makarova's La Bayadère and Michael Corder's L'Invitation au voyage. With Dowell she also did The Nutcracker in Strasbourg, Cinderella in Lisbon and Five Rückert Songs for the Rambert Dance Company. Among her theatre credits were Camino Real and Antony and Cleopatra for the RSC.

She was also a painter of note, having won the Garrick-Milne prize for theatrical portrait painting in 2000, and the National Portrait Gallery holds her portraits of subjects as varied as MacMillan, Stephen Hawking, Steven Berkoff, Roberto Gerhard, Norman Wingate Pirie and Joseph Needham. She is also the sitter in three works held by the NPG. She had solo exhibitions at the Whitechapel (1975) and Serpentine Galleries (1985–86).

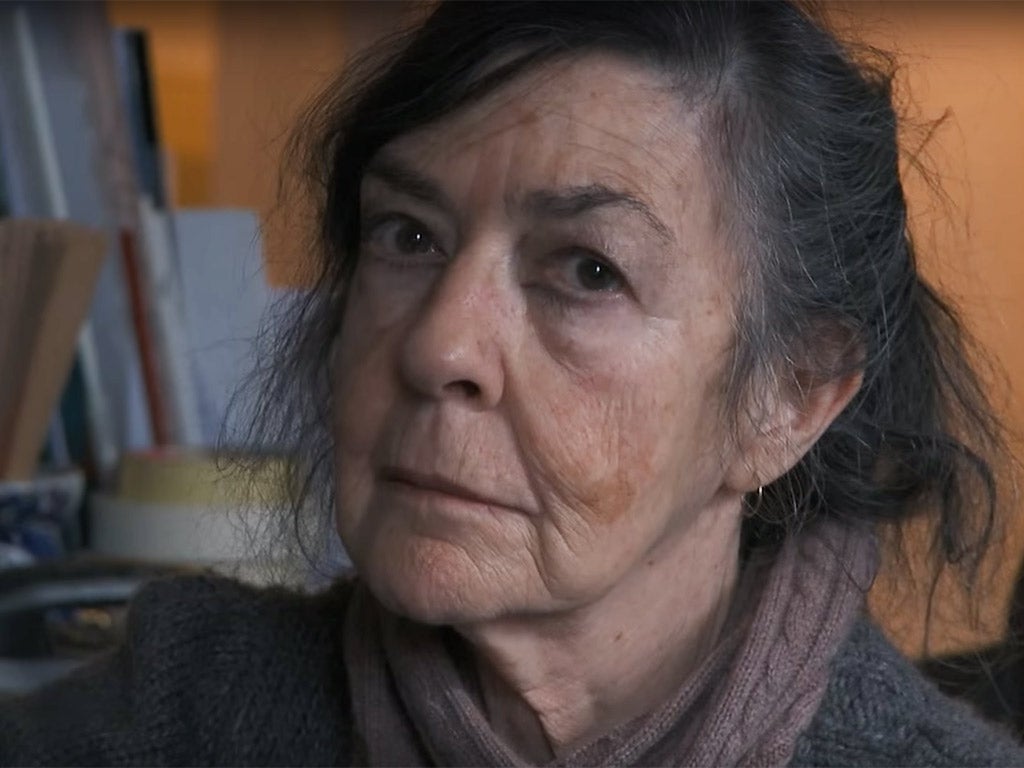

A film not yet released in the UK, Some Kind of Love, made by Thomas Burstyn, the grandson of her stepmother, shows the aged Yolanda living in the house worth millions in Hamilton Terrace in London, its stately rooms filled with art materials and bric-à-brac. “I'm a prisoner of rubbish,” she says at one point, though the narrator, her film-maker step-great-nephew, calls it “her magical house of chaos.”

Her health was poor in her later years; she had cancer in 2005, and her world-renowned elder brother, Joseph, a microbiologist and virologist who shared ownership of the house (“bought with their inheritance my grandmother forgot to steal,” remarks the narrator of the film) came back from America to look after Yolanda, though neither of them admitted to having anything much in common. Joseph, who had had a distinguished career as an HIV/Aids researcher in the US, began to notice signs of dementia in Yolanda in 2009; he had this confirmed by neurological investigation, and though it was slow to show, she developed Alzheimer's; she spent the last two years in a care home.

(Joseph Sonnabend was regarded as heroic in his Greenwich Village medical practice, which the press called the “ground zero of HIV/Aids”, because of his pioneering community-based research; he stressed the importance of safe sex. He is also a composer, and now lives alone London, looked after by his and Yolanda's Albanian “live-in handyman”, Arjan.)

Yolanda was born in Bulawayo because their Leningrad-born mother Fira needed to be in a country that recognised the medical qualification she had gained at Padua University. As a British colony, Rhodesia fitted the bill. Yolanda's father, Henry, was a German-speaking secular Jew from the part of East Prussia that was sometimes Russia, sometimes Lithuania, but part of Germany when met his wife at Padua, where he was an academic sociologist.

They went to Africa in order for him to carry out a project on Bantu tribes, but Joseph told me that he wonders whether his father's Italian mentor might have also thought it a good ploy for getting the married Jewish couple away from the dangers of Italy in the mid-1930s. Henry then taught at Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

After the War, Henry was an activist in secular Jewish matters such as helping the hundreds of thousands of displaced persons, and he lived for a time in Israel and Geneva. (In the film Yolanda is asked if she can remember any Hebrew, and to everyone's surprise, rattles off a few paragraphs of the Hebrew Sabbath liturgy.) Following the death of Yolanda's mother, her father remarried, though both children had awkward relations with their stepmother, “who buried six husbands” and seems to have made off with most of the family money in each case.

Educated in Rhodesia, Yolanda had a year at art school in Rome (the Padua connection meant that the family was Italian-acculturated) then went to her father in Geneva. Settling in England in 1954, aged 19, she studied stage design and painting at the Slade School of Art from 1955-60. She subsequently taught at the Camberwell School of Art, the Central School and at the Wimbledon School of Art.

Though she made her living as a stage and costume designer, painting was central to her existence, and the Hamilton Terrace house was filled to the gunnels with finished canvases. There were usually human faces and forms in her images, though these were sometimes so mysterious, almost evanescent, that they approached abstraction.

Family and friends maintained that for them, Yolanda was the very “idea” of the artist, someone for whom art came first, and other matters a long way after. “I didn't want to get married,” she said, “it meant cooking and looking after babies.” She added: “I had many opportunities.” She was strikingly beautiful, with raven dark hair and high cheekbones, and never lacked for lovers. In the film, Charles Hope, former Director of the Warburg Institute, says they were together about seven years.

Yolanda was at our wedding party in 1977, and we saw each other occasionally at art-world events. We were reacquainted following the traumatic break-in she suffered in the mid-1990s, when thugs got into the Hamilton Terrace house and beat her severely. I took her with me to occasional opera and theatre press nights, and I was always careful to return her to her front door, a service performed by all her many friends from this time on. The wonder of her rooms wasn't so much the clutter, but that there was so much to look and wonder at. Everywhere there was a construction of twigs, metal and glass, an arrangement of flowers, of books, a clutch of fabric, a bench where tubes of pigment competed for space with brushes – and, always, a stack of paintings.

Yolanda Pauline Tamara Sonnabend, stage designer and painter: born Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia 26 March 1935; died London 9 November 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments