Debi Thomas: Why the best black figure skater in US history is bankrupt and living in a trailer

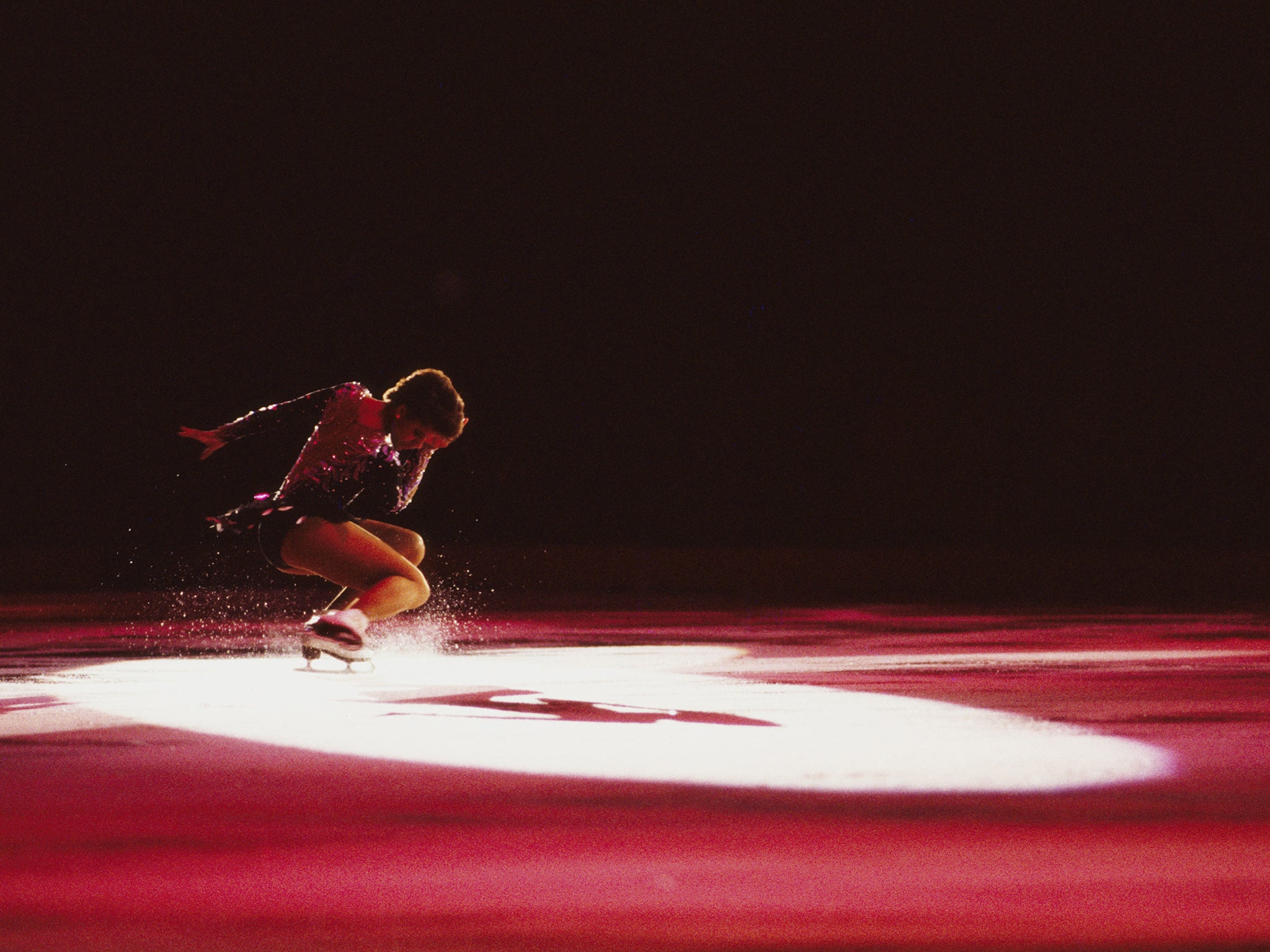

RICHLANDS, Va. — Debi Thomas, the best African American figure skater in the history of the sport, couldn’t find her figure skates. She looked around the darkened trailer, perched along a river in a town so broke even the bars have closed, and sighed. The mobile home where she lives with her fiance and his two young boys was cluttered with dishes, stacks of documents, a Christmas tree still standing weeks past the holiday.

“They’re around here somewhere,” she murmured three times. “I know I have a pair,” she continued, before trailing off. “Because — what did I skate in? — something. They’re really tight, though, because your feet grow after you don’t wear them for a long time.” Her medals — from the World Figure Skating Championships, from the Olympics — were equally elusive: “They’re in some bag somewhere.”

Uncertainty is not a feeling Debi Thomas has often experienced in her 48 years. She was once so confident in her abilities that she simultaneously studied at Stanford University and trained for the Olympics, against the advice of her coach. She was once so lauded for the lithe beauty she expressed on the ice that Time magazine put her on its cover and ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” named her athlete of the year in 1986. She wasn’t just the nation’s best figure skater. She was smart — able to win a competition, stay up all night cramming, then ace a test the next morning.

She wanted it all. And for a time, she had it. After Stanford came medical school at Northwestern University, then marriage to a handsome lawyer who gave her a son — who in turn became one of the country’s best high school football players. Higher and higher she went.

Now, she’s here. Thomas, a former orthopedic surgeon who doesn’t have health insurance, declared bankruptcy in 2014 and hasn’t brought in a steady paycheck in years. She’s twice divorced, and her medical license, which she was in danger of losing anyhow, expired around the time she went broke. She hasn’t seen her family in years. She instead inveighs against shadowy authorities in the nomenclature of conspiracy theorists — “the powers that be”; “corporate media”; “brainwashing” — and composes opinion pieces for the local newspaper that carry headlines such as “Pain, No Gain” and “Driven to Insanity.” She thinks that hoarding gold will insulate us from a looming financial meltdown, and recruits people to sell bits of gold bullion called “Karatbars.”

There’s a conventional narrative of how Thomas went from where she was to where she is — that of a talented figure undone by internal struggles and left penniless. That was how reality TV told it, when the Oprah Winfrey Network’s “Fix My Life” and “Inside Edition” did pieces on her.

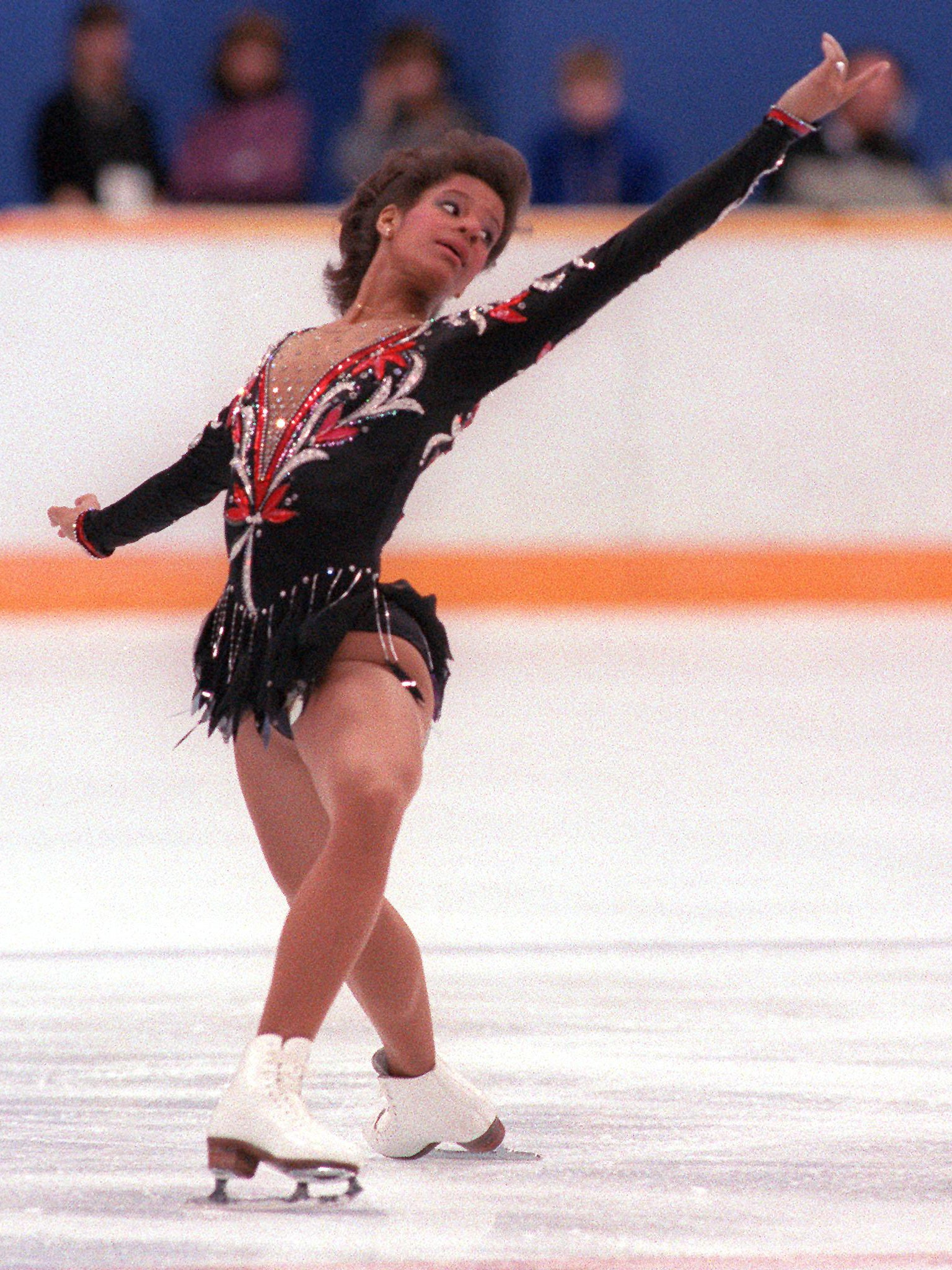

But nothing is ever that simple with Thomas. She has always bucked convention. She was a black athlete who entered a sport that had exceedingly few. She was the first champion in a generation to combine college and figure skating. She proclaimed unimaginable ambitions — such as becoming an astronaut after securing her medical degree — and dared you to doubt her.

“She’s got all these degrees,” fiance Jamie Looney said as he watched television with Thomas inside the trailer. “She’s a doctor. She’s a surgeon. And she’s here. I’ve got one year of community college. I know why I’m here. I look at her, wondering, ‘Why are you not working somewhere else?’ ”

Such comments upset Thomas. “People are all like, ‘Get a job,’ ” she said. “And I’m like, ‘You people are fools.’ I’m trying to change the world.”

* * *

Richlands, populated by coal miners with few mines to plunder, would seem to be an odd place to launch such an effort. The per capita income is less than $20,000, and the few industries left booming in the wake of mining layoffs include cash-express shops and pain-management clinics. Thomas, riding shotgun as Looney steers a silver SUV on a recent afternoon, passes several such establishments before arriving at a country market.

She greets the store’s owners — “I just signed them up for Karatbars, which will help them a lot,” she later says — and settles into a booth. Her hair is frazzled. She wears a big, poofy red coat. On her wrists are two bracelets. One is inscribed with “Believe.” The other, “Reimagine.”

It quickly becomes apparent that Thomas, for all of her talents, is not a good storyteller.

When explaining what brought her to Richlands, she communicates in a rush of thoughts, linked neither by chronology nor association, and exudes frustration when listeners can’t keep up. “I’m a visionary and have an ability to put very complex things together,” Thomas says. “And most people don’t get that.”

She says she wants to help a community she frequently describes as having “socioeconomic struggles.” In 2014, she launched a GoFundMe.com campaign to fund a YouTube.com “show about reality” — not to be confused with a “reality TV show” — that would expose life’s hardships and star Thomas. She says she also wants to enlist Richlands’ neediest as affiliates of Karatbar — which would pay her a recruitment commission — so they could earn “passive income” if they recruit others to sell the tiny bullions.

Her fiance, a gregarious unemployed coal miner, sits at her side. He hasn’t said much, but looks exasperated. “I want a normal relationship,” Looney says.

“I don’t want to be normal,” she replies. “Normal is not quite right. Normal is not excelling. That’s why they call it normal.”

She pauses. “I’m very misunderstood because I look at the world differently,” she continues. “You can call it the Olympian mentality.”

* * *

Excelling has always been very important in Thomas’s family. Her grandfather, Daniel Skelton, received a doctorate in veterinary medicine at Cornell University in 1939, the only African American in his class. Her mom, who split from Thomas’s dad when Thomas was 9, was a computer engineer when the field had few women and fewer blacks. Her brother, Richard Taylor, earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from the University of California at Berkeley, then a master’s in business at Stanford University.

“I guess I’m somewhat underachieving,” Taylor said.

Anyone would be when compared with Debi Thomas. Growing up in San Jose, Taylor said his sister always talked about becoming a doctor and loved mechanics. “One Halloween, she made herself into a calculator,” Taylor said. “You would push the buttons . . . and she would give the answer. Even as a kid, she had an engineer’s mind.”

But she also had the body of an athlete. And after her mom took her to an ice show, Thomas thought she would give it a try. When that lark transformed into something much more serious, when her coach realized he had a prodigy on his hands, when she got deeper into the byzantine and fiercely political world of figure skating, there came a choice. Skating — or school?

“Eighth grade came along and she comes in second in the nation and her coach wanted her to quit school,” her mother, Janice Thomas, said. Instead, she enrolled in high school near an ice rink in Redwood City, Calif., and for four years her mom drove 150 miles per day — school, then practice, then home. When she dispatched her college application to Stanford, the word she used to describe herself: “invincible.”

“Some people are told, ‘You can’t do that,’ and it crushes them,” her mother said. “Other people say, ‘I’ll show you.’ ”

Other pressures saddled Thomas, though her family isn’t sure she noticed it. Taylor said he sees his sister whenever commentators remark on professional tennis player Serena Williams’s muscles. Figure skating was — and remains — an intensely white and affluent sport, he said, and judges recommended that Thomas “play down certain aspects of her looks,” he said. “It was couched in language that the person making the comments wouldn’t interpret it racially, but I did.”

Thomas ultimately got three nose jobs, brought in a ballet instructor to feminize her aesthetic and, between the ages of 18 and 21, was considered the only one capable of taking down the worldwide juggernaut of women’s figure skating, East Germany’s Katarina Witt.

“She was the only one who could really beat me,” Witt recalls.

And though she once did — batting Witt down to second place in the 1986 World Figure Skating Championships — it often appeared to be a joyless pursuit. She fretted about the Olympics. “I really want it over with,” Thomastold Rolling Stone magazine before the 1988 Winter Games. “Last week,” she added, “I thought I was going to throw myself through the glass windows at the rink.”

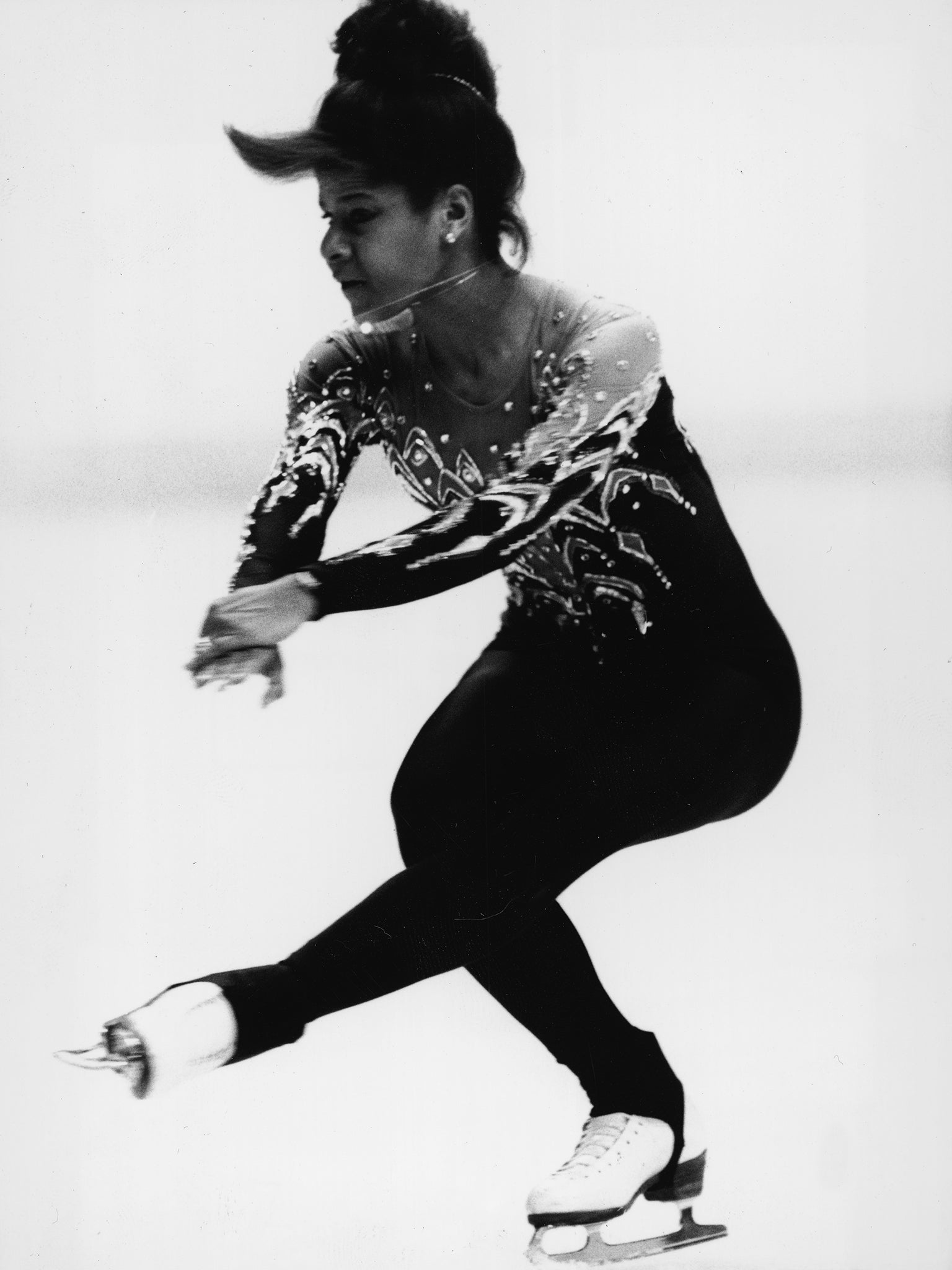

Then came the moment. Thomas had skated with precision and confidence in the first Olympic event and would take gold if she stuck the longer performance.

She and her coach had planned two triple-revolution jumps in quick succession at the segment’s beginning — something no other top female skater had done — worrying ballet instructor George de la Peña, who had helped Thomas with her routine. “Why not give her some space before the big risky stuff?” he recalled saying. But Thomas thought she could land it.

The first, she did. The second, she flubbed.

Thomas knew it was over seconds into the routine. “I’m sorry,” she mouthed to her coach after she finished, eventually taking the bronze medal. She looked disappointed. But her expression conveyed something else: relief.

And though she once did — batting Witt down to second place in the 1986 World Figure Skating Championships — it often appeared to be a joyless pursuit. She fretted about the Olympics. “I really want it over with,” Thomastold Rolling Stone magazine before the 1988 Winter Games. “Last week,” she added, “I thought I was going to throw myself through the glass windows at the rink.”

Then came the moment. Thomas had skated with precision and confidence in the first Olympic event and would take gold if she stuck the longer performance.

She and her coach had planned two triple-revolution jumps in quick succession at the segment’s beginning — something no other top female skater had done — worrying ballet instructor George de la Peña, who had helped Thomas with her routine. “Why not give her some space before the big risky stuff?” he recalled saying. But Thomas thought she could land it.

The first, she did. The second, she flubbed.

Thomas knew it was over seconds into the routine. “I’m sorry,” she mouthed to her coach after she finished, eventually taking the bronze medal. She looked disappointed. But her expression conveyed something else: relief.

“Well,” she told her coach. “Back to school.”

* * *

Thomas talks a lot about what she calls the “Olympian mentality.” It’s a frame of mind among elite athletes that they can will themselves to excellence. Self-doubt and vulnerability are banished. Confidence is everything. Triumph is within reach.

William T. Long, once an academic at the Los Angeles university where Thomas did her residency, saw this psychology at work. Everyone knew Thomas could do the procedures. Patients loved her. But her grades weren’t outstanding. There was concern that she wouldn’t pass the boards. “And she did it,” he said, “against the critics and against many odds.”

But that victory also betrayed what would become her signature weakness. Long never saw her appear to be insecure and came to recognize her confidence as a “two-edged sword.” It drove her to take greater risks than others would. It made her difficult to coach. Some disliked her because of it.

“She wanted and expected to be treated like a star,” said Lawrence Dorr, who offered her a prestigious orthopedic fellowship at the Dorr Arthritis Institute in Los Angeles, but quickly realized he couldn’t work with her. “But in orthopedics, she knew she wasn’t a star,” Dorr said. He added: “She would argue back. It was almost like she was contrarian, like she was trying to argue with everything I do.”

Difficulties with other medical professionals would come to define Thomas’s career as she left one institution after another after short periods of time. Her first stop was in Champaign, Ill. Then another in Terre Haute, Ind. “I’ve never lasted anywhere more than a year,” she said. What she viewed as commitment to perfection, others perceived as recalcitrance. “Olympian mentality is rough because you just get frustrated with how everybody does everything,” Thomas explained in a YouTube video. “Everything needs to be done with excellence. I’m a fixer.”

If she could be her own boss, she thought things would improve. So in 2010, she left her husband and 13-year-old son — whose school year she said she didn’t want to disrupt — and moved to Richlands, where she opened a private orthopedic practice at the Clinch Valley Medical Center. But Thomas — a specialist in a sparsely populated area, with no business experience — was soon falling behind on bills, burning through savings and clashing with other doctors.

Around this time, she treated a boy’s broken wrist, and his dad asked her out. The charming man lived in a gray trailer by the river. She and Looney began an affectionate, but combustible, relationship. She realized that Looney, who had spent years in the coal mines, had an addiction to prescription narcotics. And though she was dating him, according to Virginia Board of Medicine records she said she prescribed him drugs to “wean him off the narcotics.”

As Thomas’s troubles mounted, Long said he received lengthy, 10-page e-mails from his former student. They were “rambling,” he said, laced with suspicion that the medical system was conspiring against her. Whatever was troubling Thomas, he said, was “progressive” and worse every time he heard from her.

On April 22, 2012, Thomas and Looney had a disagreement at the trailer, says a psychological evaluation Thomas shared with The Washington Post. Thomas got hold of his gun. “She thought, ‘If I act crazier than him, he will straighten up,’ ” the report says. “She then went outside and shot the gun into the ground to scare him,” it also states.

Later that day, according to Virginia Department of Health Professionals records, she approached a police officer and told him she had a gun and wanted to hurt herself. He detained her and, on a temporary detention order, brought her to a hospital for treatment. Medical board records show she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Clinch Valley officials told Thomas to enter a distressed-physician program. But she couldn’t afford it. And a year later, Thomas’s staff membership and clinical privileges were revoked. Medical board records say there were “concerns of an ongoing pattern of disciplinary and behavior issues and poor judgement.”

Unable to practice — or afford $800 in monthly rent — Thomas moved into Looney’s trailer, declared bankruptcy and let her medical license expire. Last July, the Virginia Board of Medicine ordered a hearing to investigate whether she might have broken any medical laws when she prescribed narcotics to Looney and declined help for a diagnosed mental illness.

In September, Thomas contested the bipolar diagnosis at a board hearing, records show. The diagnosis was made too quickly, she said, proffering a separate evaluation conducted by a psychologist whom she had paid. The doctor, who diagnosed Thomas with depression in “complete remission,” said in the evaluation that the Olympian’s erratic behavior was not a symptom of bipolar disorder, but “naivete, overconfidence, and her expectation that if she works hard enough, she can overcome any obstacle. . . . Her experience as a world-class figure skater reinforced this expectation and confidence.”

In October, the board, citing her expired license, took no action.

It’s 9 a.m. inside the trailer, but Looney has been up for hours, worrying. The only money they have coming in is from some Social Security checks on account of the death of his children’s mother. He looks around the mobile home. He says he wants to get out of here, but doesn’t know how.

Just then, Thomas arrives from the bedroom and nestles next to him on the couch. He hands her a cup of coffee. She has just finished talking to a prospective Karatbars recruit. “I just had a really interesting conversation with a lady,” she says. “This lady completely gets me.”

“She sounded to me like she was jacked up,” Looney says of the woman, whom he had overheard speaking with Thomas.

The pair so rarely agrees that spending time with them can feel like sitting in on a couples’ therapy session. He wanted to get a job in the mines; she said he shouldn’t. She wanted him to do the “Fix My Life” show; he thought he would be embarrassed on national television. He hates their mobile home; she loves it, expressing disdain for “superficial” things.

In fact, Thomas says she loves almost everything about their life in Richlands. And there’s reason to believe her. “I didn’t know we even had this beauty in this country,” she said. “No one ever treated me badly” in Richlands, she added. “And I was like, ‘I like it here.’ ”

These days, she doesn’t have to shoulder the pressure of being the first black anything. She doesn’t have to worry about medical exams, whether a patient will recover or if her practice will succeed — because it already failed. And she and Looney, who has been clean since 2012, say they’ve calmed their relationship with a 12-step recovery program.

“I expected to be one of the leaders in joint-replacement therapy,” said Thomas, now writing a book about her life. “That was what my image was. Then I had an experience that totally changed my mind.”

On a recent afternoon, a light snow sprinkled the trailer with white. Looney and his two boys barreled outside to play. Thomas pulled on her red, poofy coat. She walked off by herself, toward the river. She tilted her head back and, with arms held out wide, was quiet as the snow pattered on her face.

Looney asked what she was doing. She said she was recreating the iconic scene from “The Shawshank Redemption,” when character Andy Dufresne escaped prison following decades of false imprisonment and assumed the same posture in the rain.

“I’m free,” Thomas called out to him. “Don’t you get it?”

Michael S. Williamson contributed to this report.

Copyright: The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks