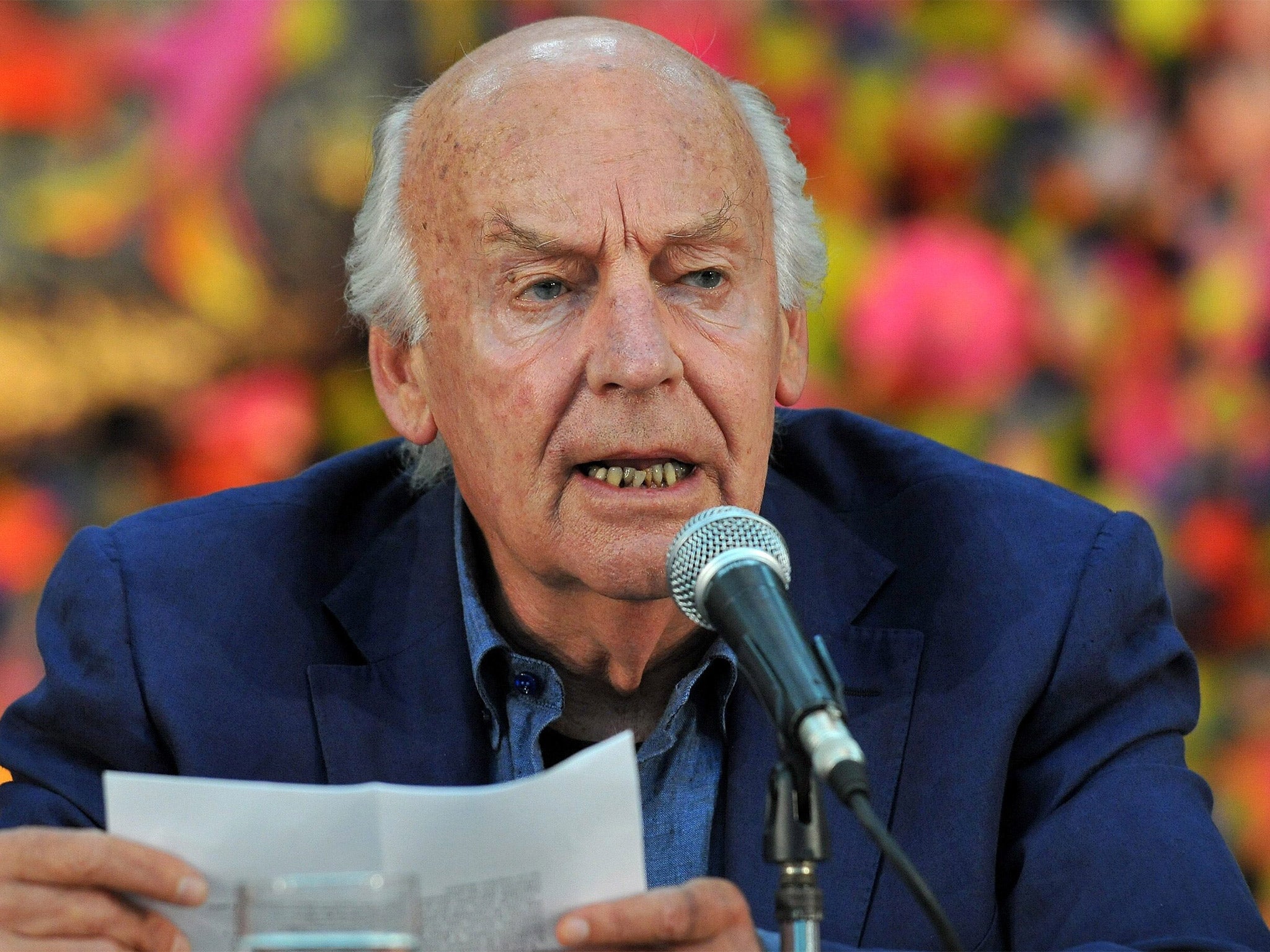

Eduardo Galeano: Author who chronicled the West’s plundering of Latin America but who later repudiated his own work

'Power is like a violin,' he once noted, 'it is held by the left hand and played by the right'

Eduardo Galeano’s anti-capitalist polemic The Open Veins of Latin America served for decades as a lodestar for leftist dissenters around the world. Last year, however, he startled his admirers when he impugned the book’s writing and scholarly value.

Galeano had been a prominent journalist in Uruguay since his teens, when he began submitting cartoons to a socialist newspaper, and he continued to write prolifically (and read voraciously) until recent years. In his 20s and 30s he edited or founded several influential political and cultural journals and twice went into exile to escape military dictatorships, first in Uruguay and then in Argentina, where he was once denounced as a “corrupter of youth.”

A hallmark of his work was the powerful and elegant epigram on the struggle for human dignity, a vision he laid out as a battle between those who conquer and those who resist. “Power is like a violin,” he once noted. “It is held by the left hand and played by the right.”

Galeano was a novelist, short-story writer, memoirist, and the author of Football in Sun and Shadow. But the work that established him as a force in radical politics and history far beyond Uruguay was The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, which first appeared in 1971.

The manifesto, promoted as a work of political economy, was a blend of Marxism, searing social history, autobiography and travelogue. Its impassioned language, stirring poems and cartoons detailed the legacy of European colonisers and Western companies that sought to loot Central and South America for its human and natural resources. The efforts by long-ago generations of outsiders to exploit the region led, he wrote, to a “contemporary structure of plunder” that continued to cause widespread impoverishment, inequality and underdevelopment. “The human murder by poverty in Latin America is secret. Every year, without making a sound, three Hiroshima bombs explode over communities that have become accustomed to suffering with clenched teeth.”

Open Veins was widely translated and sold hundreds of thousands of copies throughout the developing world, though its biggest impact was in Latin America, which was then and would remain awash in military regimes and right-wing dictatorships. It enjoyed an increase in sales in the US in 2009 when the Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who once described the book as “a monument in our Latin American history”, handed a copy to Barack Obama when they met at the Summit of the Americas in Trinidad and Tobago.

The book was not universally embraced among the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking intelligentsia, however, especially as many former developing nations such as Brazil began to experience an economic rise. Many found it irredeemably self-pitying and said it ignored many problems born from home-grown ills like destructive populist leaders on the left and nationalistic ideologues on the right.

Along with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, Galeano was among those who came in for a drubbing in the best-selling Guide to the Perfect Latin American Idiot, a 1999 collaboration between the Colombian writer Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza, the exiled Cuban author Carlos Alberto Montaner and the Peruvian journalist and author Alvaro Vargas Llosa.

Then last year, at a book fair in Brazil that feted Open Veins, Galeano made the startling announcement that he was distancing himself from his best-known work. “Open Veins tried to be a book of political economy, but I didn’t yet have the necessary training or preparation,” he said, also noting “grave errors” of leftist regimes, which seemed like an implicit rebuke of the Castro brothers in Cuba and the late Chavez in Venezuela.

Moreover, he added, his own rhetoric seemed stale and leaden, a product of an era of dictatorships and 1960s-style revolution. “Reality has changed a lot, and I have changed a lot,” he said. “Reality is much more complex precisely because the human condition is diverse.”

He was born in 1940 into a middle-class Catholic family in Montevideo with European lineage. When he was 20 he became editor-in-chief of the journal Marcha, one of the country’s most influential political and cultural weeklies. He was forced to leave Uruguay in 1973 at the start of a 12-year military dictatorship and founded the publication Crisis while in Argentina. That journal, he once said, “was cultural, but not in a narrow sense, dealing only with books and theatre and film... Not only were we offering the best of Latin American literary production, but we were looking for the unknown voices, from the country, from the walls. All the voices not sanctified by those in power.”

After a coup in Argentina in 1976, Galeano left for post-Franco Spain to escape death threats. “The schedule for calling in threats, sir, is from six to eight,” he told one caller.

The phenomenal success of Open Veins led to three more volumes in a series, “Memory of Fire” that was published throughout the 1980s. He returned to Montevideo in 1985.

His 1978 memoir Days and Nights of Love and War was an acerbic and surreal portrait of life under the dictatorships in Uruguay and Argentina. His other notable books, including The Book of Embraces (1989), Voices of Time: A Life in Stories (2004) and Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone (2008), were often impressionistic vignettes of art, politics and people. And, like most of his work, they hewed to his belief in the power of language to provoke social and political change.

“Perhaps I write because I know that the people and the things I care about are going to die and I want to preserve them alive,” he said. “I believe in my craft; I believe in my instrument. I can never understand how writers could write while cheerfully declaring that writing has no meaning. Nor can I ever understand those who turn words into a target for fury or an object of fetishism... Slowly gaining strength and form, there is in Latin America a literature that does not set out to bury our own dead but to perpetuate them.” He died of lung cancer.

Eduardo German Hughes Galeano, author: born Montevideo 3 September 1940; married firstly Silvia Brando (marriage dissolved), secondly Graciela Berro (marriage dissolved), 1976 Helena Villagra; died 13 April 2015.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks