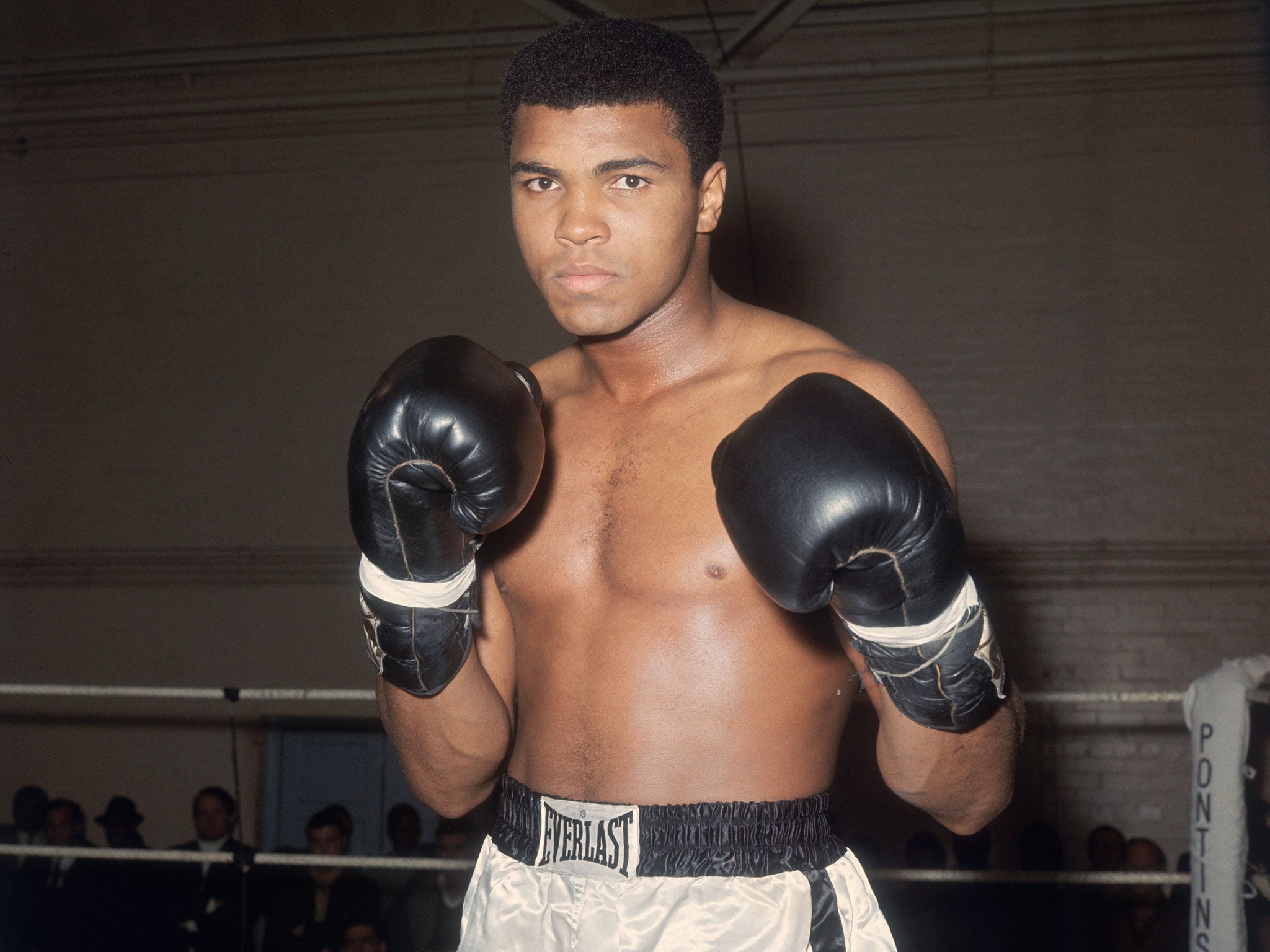

Muhammad Ali dead: 'The Greatest' who came to define an era in America and beyond

The boxer played many roles during his career - from martyr to champion, hate figure to global hero - all which helped him become as important outside the ring as he was in it

Nowhere do sporting heroes shape history and personify eras like America. Jesse Owens shamed Hitler, and Jackie Robinson integrated baseball. Babe Ruth was the Roaring Twenties, while Michael Jordan was the epitome of 90s cool. But none of them can hold a candle to Muhammad Ali.

He was a one-off. He fought against the racial evils of his time, and ended up as a symbol of triumph over them. In the process he staked a claim to being the most famous American of the second half of the 20th century, beloved by blacks, whites and every other shade of human colour. From braggart to champion, from hate figure to martyr, from beloved global hero to the final, wrenchingly sad and Parkinson’s-ravaged figure – there was scarcely a role he did not fill.

He started out of course a boxer, one of the finest heavyweights to walk the earth. But magnificent champion that he was, boxing was only a vehicle. Ali’s greatest fight, to borrow the title of an enthralling HBO movie in 2013, was not one of his epic battles against Joe Frazier or George Foreman – but the one outside the ring, in the US Supreme Court, against his conviction for refusing the military draft during the Vietnam war.

The Court’s unanimous ruling in the summer of 1971 to overturn the conviction was Ali’s supreme victory and vindication, and the watershed of his career, both as sportsman and national figure. The boxer that returned to the ring was different. Gone was the electrifying speed of the Ali who was stripped of his titles and licence to box in 1967, replaced by a post-1971 model that relied on grit, courage and wile. As for Ali the citizen, the verdict hastened his metamorphosis from lightning rod for controversy to certified national monument.

It’s easy to forget that for most of the 1960s, Ali was anything but universally adored in the US. Obviously, he was fabulously talented at his chosen craft, and hilariously funny besides an unfailing quote machine up there with the likes of Dorothy Parker and Oscar Wilde. But he was also brash, vain, with a penchant for saying things that scared white America stiff.

By the early 1960s it was clear the civil rights movement would not be denied. But while Martin Luther King projected modesty, fraternity and non-violence, Ali ostensibly took another path. Days after he stunned every oddsmaker by winning the title from the fearsome Sonny Liston in 1964, he embraced not King’s movement but the Nation of Islam that preached – so it seemed to white America – not just black separatism but black supremacy.

Black men were supposed to have comforting names, evoking spiritual leaders and American heroes. Instead Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali, disciple of Elijah Muhammad, the Nation’s founder. Typically, Ali revelled in being cocky. “I am America,” he famously proclaimed. “I am the part you won’t recognise, but get used to me. Black, confident, cocky – my name, not yours. My religion, not yours. My goals, my own. Get used to me.”

Later on, people came to love Ali for his irreverence towards the established order, his taste for saying out loud what others dared not say. In the 1960s though, he was among the most turbulent and polarising figures in the country’s most turbulent and polarising decade. And a giant part of the controversy was Vietnam.

When Ali first became famous, people had faith in government and its ability to make the right decisions. Vietnam was no exception. In its early stages the war was widely popular. Count on Ali however not to toe the line – and furthermore, link a distant Asian war with the continuing race war in the American South.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy 185+ fights a year on DAZN, the Global Home of Boxing

Never miss a fight from top promoters. Watch on your devices anywhere, anytime.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“My conscience won't let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people – some poor hungry people in the mud – for big powerful America,” he said. “They never called me n*****.”

In those few words, he summed up the turmoil and agony of the 1960s in America.

Indeed, you may ask what would have happened to Ali’s reputation (quite apart from the subsequent history of the US) had Vietnam been a success. But as the war grew steadily more unpopular, people came to understand, and agree with, Ali’s refusal to fight in it. “I’m not going 10,000 miles from home... to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over.” And if he ended up in jail: “So what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.” The Supreme Court’s 8-0 ruling, accepting that he had been a legitimate conscientious objector, sealed his triumph.

By then, it was dawning on Americans that whatever they thought of Ali’s convictions, he had the courage of them, and the readiness to pay the price for them. “His power no longer resided in his fists,” wrote a biographer, Thomas Hauser. “It came from his conscience.” And this realisation extended back to the boxing ring, once the defrocked champion was allowed to resume his chosen sport.

Pre-1967, so transcendent were Ali’s skills and so complete his domination, that the taunting kid who produced doggerel to predict how many rounds opponents would last was never really put to the test. So fast was he, they could barely lay a glove on him. But the Ali that emerged from his enforced four-year hiatus was a different fighter.

The pride was the same, but he was slower. Now he had to take it as well as dish it out. There was no braver or – as many would say when his physical condition later was so visibly deteriorating – more foolhardy fighter. But you had to admire how Ali withstood the batterings of Frazier and Foreman. In his defeat by the former in 1971, Ali achieved a nobility he never did in those easy earlier wins. He proved he had no fear.

By this time too, his behaviour, and his politics, were mellowing. He parted ways with Elijah Muhammad, embracing a less threatening, more King-like and universalist approach. His abuse of Frazier as a “gorilla” and an "Uncle Tom" demeaned him. But after their third and climactic battle, the 1975 ‘Thrilla in Manila’ Ali apologised: “I called him names I shouldn’t have called him. I apologise for that. I’m sorry. It was all meant to promote the fight.”

Then came the final harrowing fights, when Ali’s deteriorating condition was only too evident. His friends pleaded for him to retire, and not tarnish the memories, but he didn’t listen – even the greatest fighters rarely do, and one thing Ali the showman never lost was faith in his own powers. Yet even that wretched coda to his career somehow only added to his aura.

The final years were pathos. The “Louisville Lip” once never lost for words, could now produce but a slurred mumble. So bad was the Parkinsons that you held your breath praying he would not stumble at the moment of his apotheosis when, unannounced, he emerged to light the Olympic flame at the 1996 Atlanta games. But as always Ali did not disappoint.

The closest parallel to him was perhaps Nelson Mandela. Both were black, both were rebels who took on a system of racial injustice and won, and did not gloat in their triumph. Both had the rare quality of making humanity of every hue feel better about itself. And in the process, America forgave him everything.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks