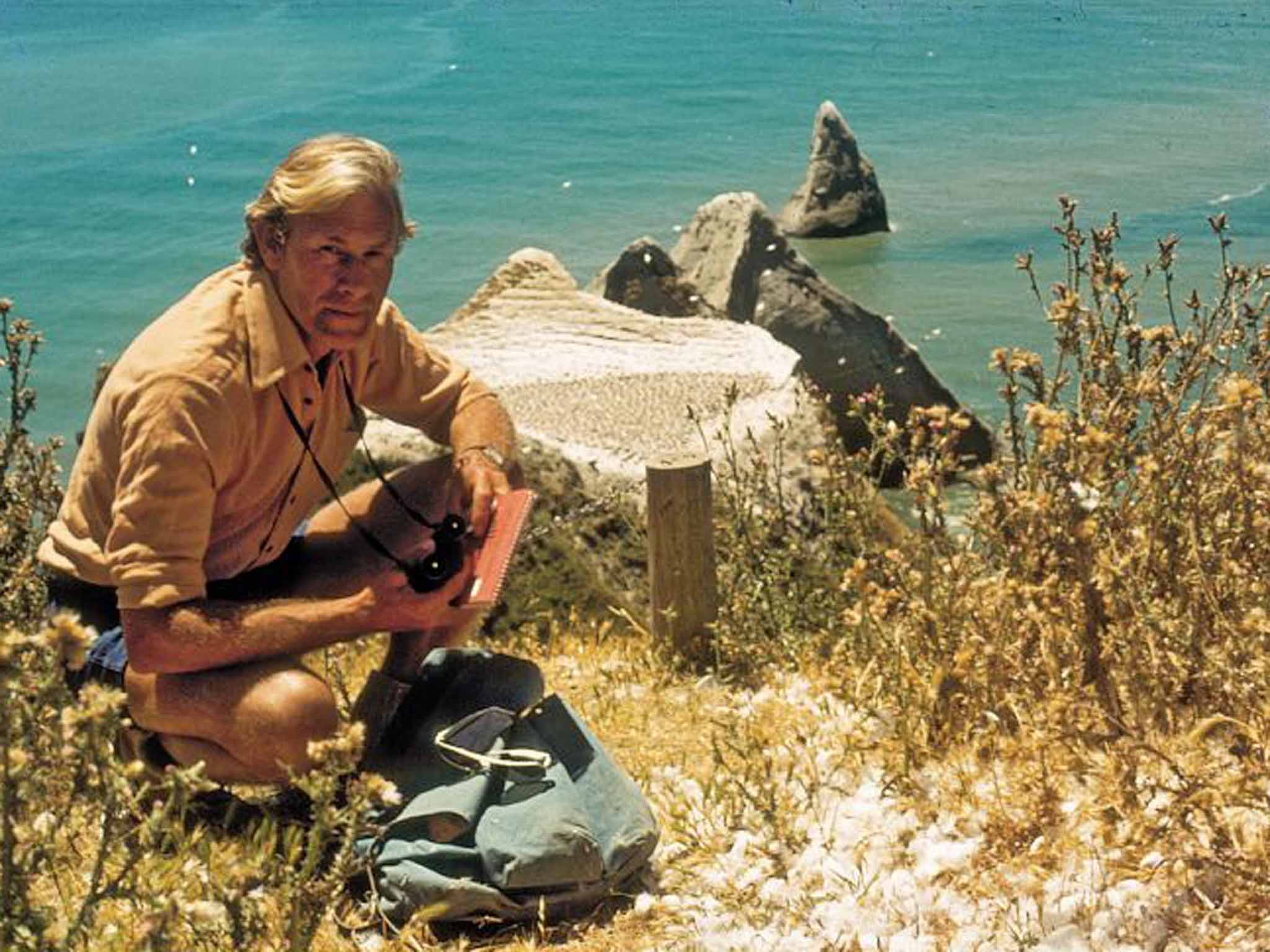

Doctor Bryan Nelson: Environmental activist and ornithologist acclaimed as the world's leading expert on the Northern gannet

One of his proudest achievements was pressing the Australian government into making Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean a national park

Bryan Nelson was a wildlife activist, environmentalist and ornithologist known as the world's leading expert on the largest seabird in the Atlantic, the Northern gannet (Morus bassanus). Such was his love for the white, black- wing-tipped, plunge-diving seabirds that he and his equally intrepid wife and researcher June spent three years, including their honeymoon, on the uninhabited (except for two lighthouse keepers) Bass Rock off the south-east coast of Scotland.

From 1960-63 they lived in an uninsulated 14-by-8ft garden shed, lit by a paraffin lamp, inside the ruined walls of the ancient St Baldred's chapel which gave scant protection from gale-force winds. "On the stormiest nights, in case the wind blew the roof off, Bryan sat with his arms round his three tall piles of notes and writings," June recalled. Their supplies arrived once a fortnight on the lighthouse relief boat.

Nelson immersed himself in all things gannet, recording their sounds, habits and body language. He would amuse his zoology students at Aberdeen University by imitating the birds' flexible body shapes and rab-rab-rab call, which echoed through the university corridors. He demonstrated how gannets engage in "beak-fencing", frenetically fencing with their beaks, not aggressively but to strengthen the bond with their mate.

He took stunning photographs of gannets retracting their wings to dive-fish from 100 feet above the water, splitting the surface at more than 60mph before miraculously "swimming" for more than a half a minute 60 feet below the surface to snatch a sardine snack: lots of snacks, hence the expression "eat like a gannet."

"When describing 'sky-pointing' – when, for the chicks' safety, a gannet signals to its partner that it is about to leave the nest – he became a gannet," said one of his former students Tom Brock, now CEO of the Scottish Seabird Centre in North Berwick, where Nelson was a special advisor and inspiration. "He used his whole body to imitate that distinctive posture – unforgettable! And woe betide any student that brought any hint of anthropomorphism into their descriptions of animal behaviour."

Nelson lectured at Aberdeen from 1969 until he formally retired in 1985. His 1978 monograph on gannets is globally respected as a definitive textbook, as are his studies of Pelicaniformes, the group of seabirds including pelicans, boobies, cormorants and frigatebirds. He was a freewheeling environmental researcher in the days before bureaucracy and over-zealous health and safety concerns threatened such free-spirited humans with extinction.

The Nelsons also lived rough on two of the Galapagos Islands off Ecuador, studying frigatebirds and boobies. They lived in a tent on a beach, usually unburdened by clothing as they observed their birds or danced and pranced in the sand and surf. Having heard of this intrepid couple, the Duke of Edinburgh, President of the WWF (now the Worldwide Fund for Nature), ordered the royal yacht Britannia to drop anchor off the Galapagos. They had time to slip on some clothes before he invited them on board for welcome sundowners. Nelson recalled himself looking like Robinson Crusoe as they boarded, "barefoot with patched-up shorts covered in albatross vomit."

On the islands, the Nelsons had no water. They dug a pit in the sand, lined it with black polythene, covered it, filled it with seawater and waited for fresh water to condense on the top. That gave them about a pint a day. "Getting a photograph did rather take precedence," June recalled. "I remember my indignation when my hand was held in the vice of an albatross beak. It needed two hands to prise that apart and there was Bryan looking for his camera! Our 'good' water' was used first for rinsing his precious negatives but was recycled for hair-washing." As a result of their work, the Nelsons counted Prince Charles and Sir David Attenborough among their greatest admirers.

They spent much time studying Australasian gannets at Cape Kidnappers, near Napier, New Zealand, a Pacific headland named after a 1769 attempt by Maori to abduct a member of Captain Cook's HMS Endeavour crew. Moving from desert islands to desert oases, at Azraq, Jordan, Nelson studied migrant birds who sought out the Azraq oasis, the only source of fresh water within thousands of square miles.

One of his proudest achievements was pressing the Australian government into making Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean a national park, largely to save the endangered bird, the Abbott's Booby, which breeds only on that island, nesting high in the jungle tree canopy. He wrote many papers and several books, including On the Rocks, published last year with magnificent artwork by his friend and fellow Yorkshireman, the wildlife artist John Busby, who died a few weeks before him.

Joseph Bryan Nelson was born in the textiles town of Shipley, West Yorkshire, in 1932. He left Saltaire Grammar School at 16 to help keep his family. He may have got his adventurous spirit from his father, who had run away to sea as a teenager. Bryan won a place at St Andrews, graduating in zoology, followed by a DPhil from Oxford, studying animal behaviour with Niko Tinbergen and Mike Cullen. He married June Davison, a tax office worker from Rawdon, Leeds, on New Year's Eve 1960, and they would spend the next 55 years together at work and play.

"We met under a table sheltering from the rain at Spurn Point [on the Humber estuary], watching and ringing birds on migration," June recalled. "I offered him half my apple, which he reluctantly accepted." The Adam and Eve analogy would continue on the Bass Rock and elsewhere, where they were able to frolic as nature intended.

Nelson, who had suffered from a genetic heart defect, died at home in Kirkcudbright, where he had moved, for health reasons, from a remote old iron mine house on a farm track in "our secret valley" in Galloway. He and June's twin siblings, Simon and Becky, have followed in their parents' adventurous footsteps. When Nelson died, Simon was on the Uzbek border on an environment-awareness cycle trip from Vietnam to Paris, while Becky was in the Australian outback. Green in life, green in death, Nelson opted for a "green burial" at Roucan Loch outside Dumfries.

Bryan Nelson, zoologist, environmentalist and ornithologist: born Shipley, West Yorkshire 14 March 1932; married 1960 June Davison (one daughter, one son); died Kirkcudbright 29 June 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments