Andrew Mitchell: 'It's no good feeling hard done by'

In his first interview since 'plebgate', the former Chief Whip opens up just enough to concede that, in politics, you have to take the rough with the smooth, even if that means leaving a job you love. Sarah Morrison meets Andrew Mitchell

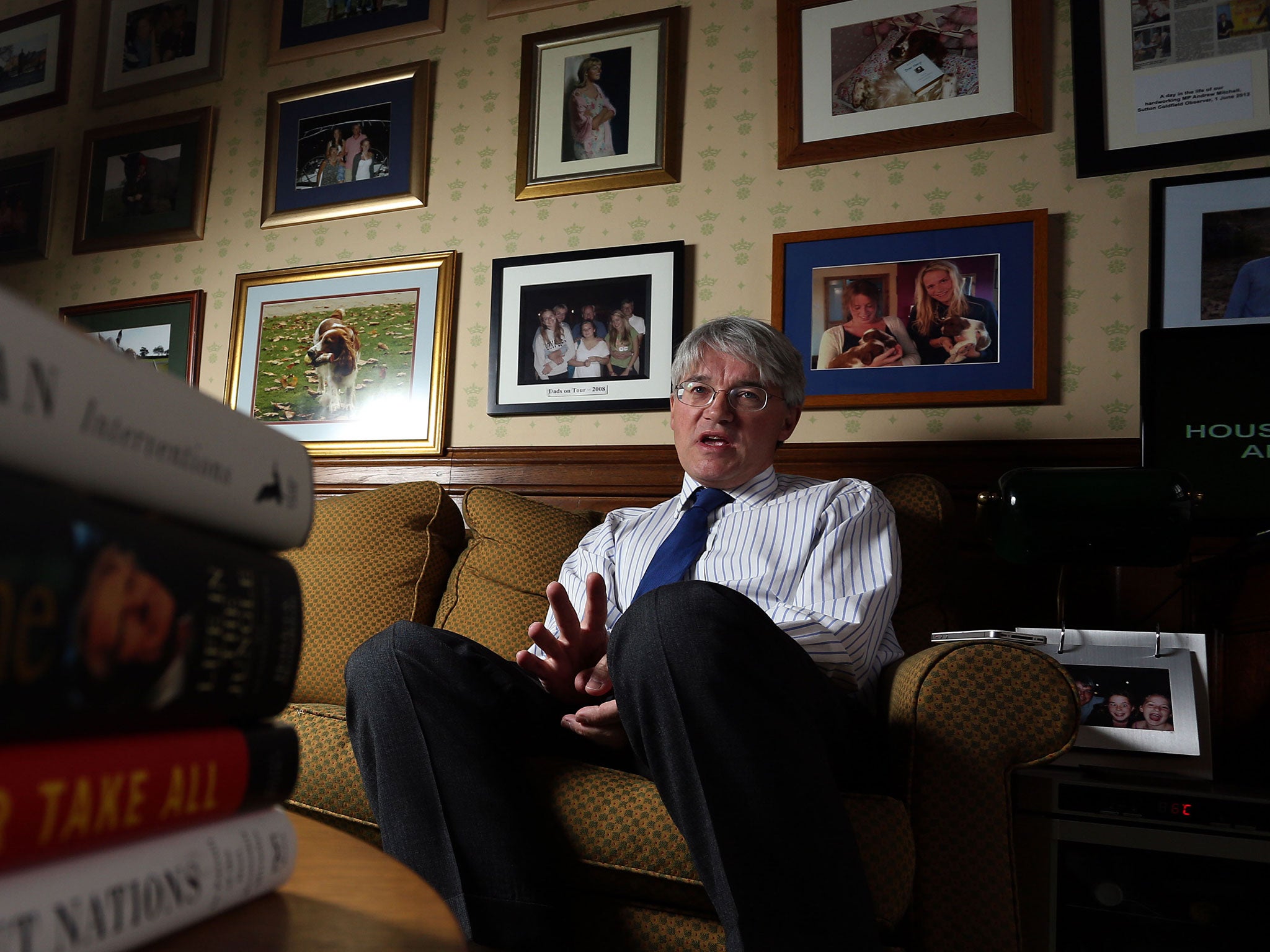

"Do whatever you like so long as you don't stiff me," jokes Andrew Mitchell, as our photographer starts snapping. Forget plebgate, police scandals, press intrusions or being ganged up on; the former Chief Whip is now wary of an unflattering photo. I can't say I blame him.

For a man once dubbed "the luckiest minister in the Cabinet", Mitchell now has more reason than most to fear ridicule. It has been eight months since he allegedly called Downing Street policemen "plebs", lost his job in the Cabinet, and was catapulted into the glare of the media spotlight. He has always denied the claim and is the first to admit that he finds it incredible. "If you had told me what happened to me last September could happen in Britain today, I simply would not have believed you," he says, sincerely.

But now, as we sit opposite each other in his large parliamentary office – just down the way from Vince Cable – one could be forgiven for thinking we were located in a different time period. I am here under strict orders to ask the Tory minister only about international development ahead of the G8 – he served as secretary of state for almost three years in Cameron's government and five in opposition.

His old red box is still proudly displayed by his desk, alongside a pile of books (including Confessions of a Eurosceptic by his friend and former Conservative minister, David Heathcoat-Amory), a George Bush action figure, a pretend panic button, a picture of himself with Mo Farah on the wall and a "World's Best Dad" mug taking pride of place on his window sill.

Mitchell is here to promote the importance of development aid "at a time of significant economic difficulty in Britain". On this he is fluent and confident. He talks about the "common ground" carved out by the coalition, which understands that development will not succeed "unless you tackle corruption, unless you tackle instability and conflict; unless you have the rule of law so investors know they will be well treated".

We chat about family planning, violence against women, tax avoidance ("the stars are aligned" to tackle this, he says) and Syria. On this, like others, he is knowledgeable and emphatic. "Helping with non-lethal equipment is clearly the right thing to do; going beyond that is fraught with difficulty."

But engaging as he is, it is hard to avoid the gate-shaped elephant in the room. Mitchell has not spoken to any journalist about the scandal since he claimed on a Channel 4 Dispatches programme in February that he was "stitched up".

The public has softened its approach to him in recent months, he tells me. It turned out that an email allegedly sent by a member of the public claiming to be an eyewitness to the event was actually sent by an officer who was not even there. CCTV cast doubt on the police version of events, while at least three officers have been arrested so far.

But Mitchell is clearly still bruised. When asked about the incident, his confidence falters. His answers are peppered with innuendo. He jumps to the defence of Lord Feldman, his friend and co-chair of the Conservatives, who was alleged to have branded Tory activists "swivel-eyed loons", because he does not "think just because someone is a politician they should [be] assumed to be a liar". Those allegations were denied by Lord Feldman.

Mitchell adds: "We do have a tradition in Britain, which I hope is still true, that you are innocent until proven guilty."

Returning to his own predicament, he considers every word before he lets himself utter anything. He claims that, even before the Channel 4 Dispatches documentary aired, his constituents on the whole believed him. And indeed, "I was told by one ITV journo when they came down into the centre of Sutton Coldfield to try to find what my constituents were saying about me, they couldn't find anyone to badmouth me," he says, not quite bringing himself to smile.

"There was another incident on the high street... where a chap stopped his car, held up traffic, jumped out and gave me a hug. He didn't say a word, just got back in his car and drove off. So my constituency was really supportive and decent."

On the police, however, his faith is clearly shattered. He resorts to the don't-say-yes-or-no game, when I ask him about the allegations that the country's most senior policeman, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, discussed details of the police inquiry to journalists. "Did you find it 'profoundly shocking'?" I ask. "I did," he replies, before looking away, as if he were a young boy caught snitching on his elder brother.

"I was brought up with the Dixon of Dock Green view of policing," he tells me, referring to the 1950s TV series. "The issue isn't me, really; the issue is if it can happen to a cabinet minister or a senior minister, then what chance does a kid in Houndsworth in Birmingham, or in Brixton, have in similar circumstances?"

While Mitchell described the Woolwich murder as an "awful reminder of an ongoing threat, which affects everyone in Britain, from the scourge of international terrorism", he clams up when pushed to give an opinion on the length of time it took officers to reach the crime scene. "I'd better not go there, I think, no," he says. At this point, he gets uncomfortable. As I ask him more, his distrust of journalists becomes clear. He won't discuss rumours about him being offered a top job in Europe, or what he thinks about the competence of the police's inquiry.

"I'll save you the trouble of trying in your absolutely brilliant and seductive way to flush me out, because you won't," he says. Confused (and in no way seductively), I press on. Why did he leave his role as minister for international development, if he loved it so much?

"I do care very deeply about it. It's no secret that I did not want to move. But in the end in politics, if the Prime Minister asks you to do something, you should do it," he says diplomatically. But then, as if he can not help himself, he adds: "But it's no secret I fought hard not to do so. People around him, William, George … and so on, all ganged up on me and said I should do it. So I did."

Does Mitchell feel like a man hard done by? "No," he says, resolutely. "It's no good feeling hard done by in politics, you know? You have to take the rough with the smooth."

He is happiest when he is talking about his daughters, and especially their shared passion for development. His elder daughter, Hannah, who is a doctor, is working in a Ugandan hospital as part of her training. His other daughter, Rosie, has been to Rwanda every year since he set up the Conservative social action project Umubano. "My daughters do inspire me. They both care passionately about the issue and I am unbelievably proud of them both," he says. While he admits both his sister and brother are "very sceptical" of aid, he says: "International development discussions around the Mitchell kitchen table are passionate and frequent."

With that, my time is up. The official Mitchell tells me that he is publishing a pamphlet on development soon, while the man who has faced more scrutiny than most could bear, talks to me about less "on-topic" issues off the record.

But I don't blame him for being coy. As I leave Parliament, two police officers reprimand me for leaving without an escort. "Who signed you in?" they ask. When I tell them it was Andrew Mitchell, they turn to each other and laugh.

Curriculum vitae

1956 Born 23 March in Hampstead, London. He is the son of Sir David Mitchell, a former Conservative MP and junior government minister.

1975 After attending Rugby School, where he is nicknamed Thrasher, he is commissioned into the Royal Tank Regiment.

1978 Graduates in History from Cambridge University, having also served as the President of the Union.

1981 Starts work at accountantcy firm Touche Ross and later Lazard bank.

1987 Young Mitchell enters Parliament as MP for Gedling, Nottinghamshire.

2001 He is elected to the Sutton Coldfield seat in the 2001 general election

2010 Becomes the International Development Secretary following formation of the coalition government, having acted as the shadow secretary since 2005.

2012 Following the first major Cabinet reshuffle, David Cameron assigns him the role of Conservative Chief Whip.

September 2012 Mitchell has a confrontation with Downing Street policemen while on his bike, allegedly calling them "plebs." He resigns from Cabinet in October.

Kashmira Gander

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks