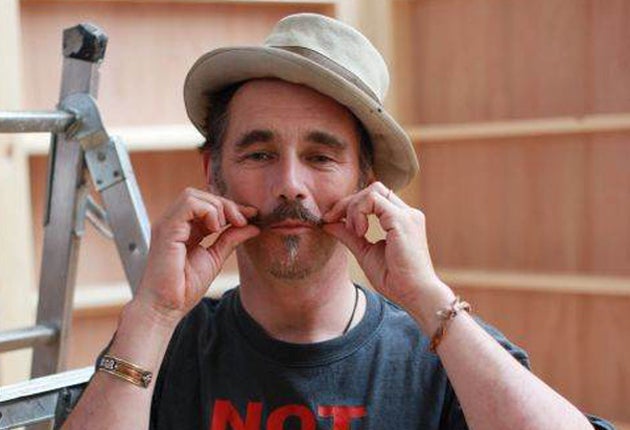

Mark Rylance: Acting is just play. You have to look for the joyful thing

Acclaimed by some as the best since Olivier, but derided by others for being 'as nutty as a fruitcake', the iconoclastic actor says pleasure is the secret behind his success

Mark Rylance practically has a trademark on the phrase "best actor of his generation". But the question is seldom asked: why is he the best? And how?

A staple of the British stage for three decades, the 50-year-old is enjoying his purplest patch yet, after a Tony award for Boeing Boeing on Broadway and last year's astonishing turn as misfit and rebel Johnny Byron in Jerusalem, Jez Butterworth's hymn to English non-conformism. Indeed, his Byron is by wide consent the stage performance of the century so far, bringing Rylance to the sort of popular acclaim rarely seen since Olivier walked the boards.

A paid-up non-conformist himself, Rylance has spoken of his own "love of mystery and a love of questions". So can he help with a mystery? Why do I enjoy watching him on stage more than I do any other performer?

Finding the answer may not be easy. Actors are notoriously unenlightening about acting. There's a scene about it in Rylance's new play, David Hirson's La Bête, which ruthlessly mickey-takes self-important thesps. "It's ludicrous to verbalise my art," says one. "For truly I become the words I say! / That chicken – when it's squeezed within your play – / I WAS that chicken, I BECAME that hen ..."

La Bête is a comedy in verse, a hit in London in 1991, when it starred Alan Cumming, but famously a flop in its native USA, where it closed after 25 performances. On the page, Hirson's script is a hilarious nugget of cod-Molière, in which a high-minded dramatist in 17th-century France is forced by his royal patron into partnership with an uncouth street clown.

Rylance plays the clown, just as he did under the same director, Matthew Warchus, in Boeing Boeing three years ago. His character, Valere, is a preening buffoon, deeply in love with himself and the charming impression he thinks he's making. He's also a force of nature, with a domineering, motor-mouth charisma Rylance admits will be "wonderful" to play – even if "to release that side of yourself into daylight is a little shocking".

Rylance is softly spoken and seems vulnerable; innocent, indeed. Received wisdom casts him as an eccentric, or even, in The Daily Telegraph's words, "as nutty as a fruitcake". Critics cite Rylance's habit of giving cryptic speeches at awards ceremonies. Receiving his 2008 Tony, he recited an obscure prose-poem by the Midwestern writer Louis Jenkins.

There's also his insistence that Shakespeare didn't write the plays of Shakespeare, which – given that Rylance was the founding director of Shakespeare's Globe theatre – raised a few eyebrows. Mention that he had Jane Horrocks pee live onstage in his Hare Krishna version of Macbeth, and you've got Rylance-as-weirdo bang to rights.

But what the Telegraph considers weird may simply be, in Rylance's case, unselfish, iconoclastic and left-wing. A champion of progressive causes, he is an ambassador for Survival International, which campaigns for indigenous peoples. His artistic tastes are esoteric: he talks about his own work with Phoebus' Cart, the company he set up with his wife, the musician/composer Claire van Kampen, as "experimental", and his Globe tenure was one ongoing investigation into Elizabethan and other elemental theatre practices. He has a hippie's distaste for matters financial, and left the Globe after a dispute over money. He laments how "the religion of today, consumerism, bombards our grosser appetites, and affects our sensitivity to the subtler things in life". Rylance's so-called eccentricity is his way of reactivating that sensitivity.

Which is all well and good, but it doesn't help with my inquiry into the mystery of his qualities on stage. In Warchus's words, "he was born with the ability to lie in an astonishingly convincing way. It's supernatural. Add to that his showmanship, and his [ability to communicate] psychological truth – which are usually mutually exclusive – and you have something virtually unique." But when I ask, for example, whether he possesses "an X-factor" that other actors lack, he comes over uncharacteristically snippy. "You'd have to ask Simon Cowell about that kind of shit."

According to Butterworth, Jerusalem demanded a lead actor "who gives you goose pimples when he walks on stage. [And] Mark just has all that naturally." Butterworth spent many years writing Jerusalem, and did so with only one man in mind for Byron: Mark Rylance. The result was a rollicking tragi-comic elegy for the demise of old England, personified by the mercurial, drug-dealing, yarn-spinning Johnny "Rooster" Byron, as he contemplates eviction – and worse – from his caravan on St George's Day.

Born in 1960 in Ashford, Kent, Rylance spent his childhood in Wisconsin, where his father taught English. He still speaks with a transatlantic twang, and his outsider status is often ascribed to that ex-pat upbringing. On the one hand, Rylance was embraced early by the mainstream: he studied at Rada, played Hamlet for the RSC and won his first Olivier, for Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, when he was 33. But at the Globe, his work was persistently ignored or patronised by critics, and in interviews at the time of his departure, a bruised Rylance abjured Shakespeare and toyed with emigrating (again) to the States.

That's all changed now. "It's five years since I've done a Shakespeare play, and I'd like to do a few more," he says. He's planning to reunite Phoebus' Cart and re-engage with "original practice" versions of the Bard. And he hopes to revive his cumbersomely titled Big Secret Live 'I Am Shakespeare' Webcam Daytime Chat-room Show, which premiered at Chichester in 2007. But that'll all have to wait until 2012, because he's holding out for a US run of his beloved Jerusalem, and is committed to playing La Bête in both London and (if it succeeds) New York.

Such is the life of an erstwhile company man turned freelance actor-for-hire. La Bête is a play about that very dichotomy: should we be team players or follow our own path? It's a question more people will be asking, says Rylance, as they are "thrown back on their own resources" in a recession. "And some may find it a great relief," he adds, putting a positive spin on economic meltdown, "that they no longer have to answer to some suit, and that there isn't some ladder they have to be progressing up all the time."

More specifically, La Bête is about art and compromise. Should artists defend the purity of their vision – or water it down to satisfy sponsors, collaborators and their audience?

In 1991, The New York Times accused the play of preaching high-mindedness while practising vulgarity. That, as the play's many defenders pointed out, is unfair – La Bête neither deplores the clown nor defends the cultured snob (played, in this revival by Frasier star David Hyde Pierce). But "it would be an ideal outcome," says Rylance equably, "if people continue to have angry arguments at the end, and for the debate about, say, commercial versus subsidised theatre to carry on long after the show".

Rylance won't take sides in that debate. "I can't judge," he says, because "I'm not able to be outside the play, to be un-influenced by knowing all Valere's lines and being him." Rylance's focus is the character and "finding a way of being present, and making every connection believable between each word, sentence, and each beat." In this case, that means encountering his inner egomaniac. "We all have vanity, don't we? And we all sometimes think, 'if I said now what I'm thinking about this person, he won't be my friend any more.' We all have a Broadmoor special hospital side to ourselves."

If Rylance has an inner Broadmoor, it's very inner indeed – although he does tell a damning anecdote against himself, about the time he and his wife gave a Q&A in New Zealand and he ruthlessly hogged the limelight. But these days, Rylance goes easy on the recrimination. "I used to be so dominated by self-criticism," he says, "that I had difficulty enjoying myself at acting for a long time."

This is as close as I get to a clue to Rylance's brilliance on stage. When I tell him that his Boeing Boeing, his Jerusalem and his hilarious Olivia in the Globe's all-male Twelfth Night are three of the most enjoyable performances I've ever seen, there's no explanation forthcoming of how he does what he does. (He cheerfully acknowledges those actors-on-acting pitfalls.) But I do get a paean to pleasure – which might be the next best thing. "I remember Jimmy Cagney in a beautiful interview he did, saying that acting is child's play. And certainly, for me, the core of it is the enjoyment of play-acting."

By this, he means not just his own enjoyment, but the audience's. Here, he goes off on one about theatre architecture. "Imagine the Old Vic with no seats in the stalls," he raves. "Fantastic! All the seats in all stalls should be removed. There should be bars in there instead, and people standing around with food and drink and the ability to slip out easily if the play is boring." Theatre should be direct, wild and fun.

"My objective in a play," he says, "is to get the audience involved. Get them out of their concerns and into the concerns of a fantasy world. So when they then step back into their lives, they've had the effect that a holiday gives you, when for a few fleeting minutes after getting home, you think, 'oh – I see what needs to be done with my life'."

But that effect, that enjoyment, depends on Rylance's own. "When I was a young actor," he recalls, saddened by the memory, "I used to bang my head against doors like a sledgehammer until they would open. Now, I just play. I look for the joyful thing. Those three parts you named were just so enjoyable. And rehearsing this play, too, I laugh so much, I worry that I won't be able to keep a straight face come the performance." So much for the mystery: to the best actor of his generation, it's quite straightforward. "Nowadays, I just really enjoy myself."

La Bête opens at the Comedy Theatre on 7 July

Curriculum Vitae

1960 Born in Ashford, Kent, the son of two English teachers. His father moved the family to the States when Rylance was two.

1976 Played Hamlet at high school in Milwaukee before going on to study at Rada.

1980 Joined the Glasgow Citizens' Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company two years later.

1990 Formed the Phoebus' Cart company with Claire van Kampen, whom he married in 1992.

1995 Named the Globe's first artistic director and led it until 2005.

2001 Starred in Intimacy, above, which featured a scene of unsimulated sex between Rylance and his co-star Kerry Fox. The film won a Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival.

2002 His cross-dressing performance as Viola in his all-male production of Twelfth Night won him the London Critics' Circle Theatre Award for best Shakespearean performance and an Olivier nomination.

2005 Won a Bafta for his portrayal of weapons expert David Kelly in The Government Inspector.

2007 Won a Tony for his Broadway performance in Boeing, Boeing.

2010 Won an Olivier for his portrayal of Johnny Byron in Jez Butterworth's acclaimed Jerusalem.

2010 Playing Valere, a "low-brow street clown", in the revival of David Hirson's La Bête at the Comedy Theatre, London.

2011 Will appear in Roland Emmerich's Anonymous, a "blockbuster" period movie said to explode the Shakespeare myth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks