Michael Caines: One-armed banquet

Michael Caines has overcome disability to become Britain's top chef – and still found time to trace the parents who gave him up for adoption

It's fair to say that there probably aren't many one-armed, adopted, Anglo-Caribbean men from Devon who hold both an MBE and a Europe-wide reputation for catering brilliance.

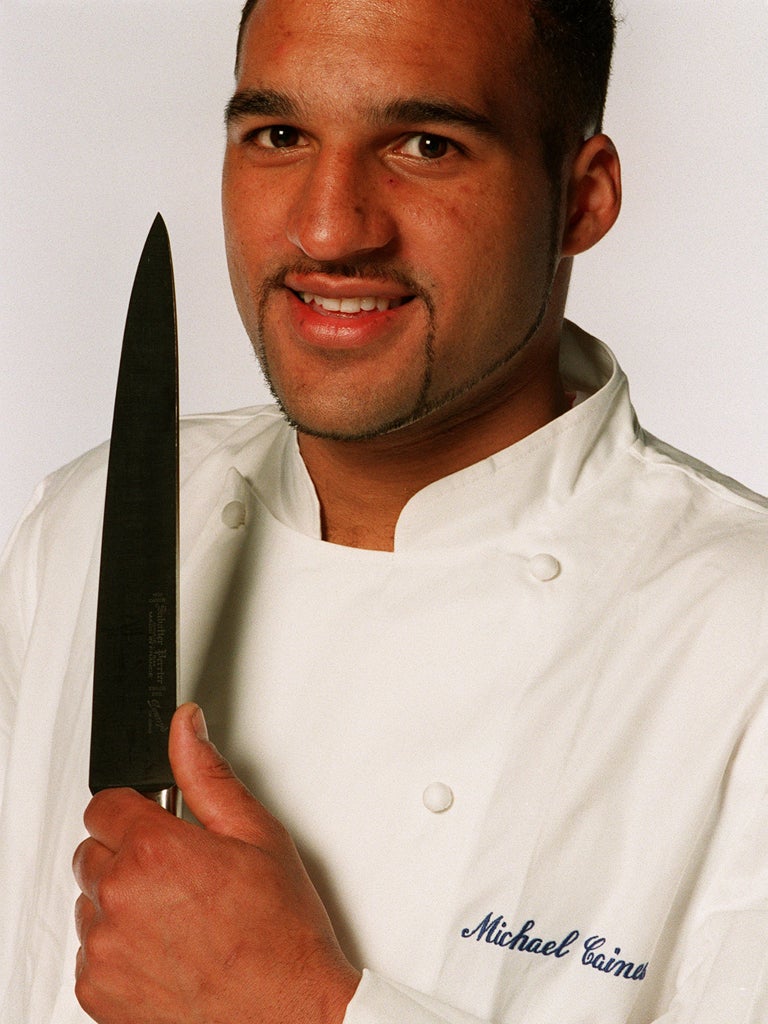

In fact Michael Caines may be the only one. Dashing, ambitious, his handsome face framed by a pencil-beard once trended by Craig David,

Caines at 42 is at the top of his game. His restaurant, Gidleigh Park Country House Hotel on the edge of Dartmoor, was this week named the UK's best all-round restaurant in the Harden's restaurant survey for the second year running (the phrase "perfect in every way" recurred in critics' reports, like they were reviewing Mary Poppins). It's an accolade that confirmed the judgement of The Sunday Times Food List which, in November, placed Gidleigh Park at the head of Britain's Top 100 Restaurants.

More famous chefs – the televisual, the celeb-tastic, the picturesquely aggressive – can only grind their teeth in envy. Caines's cooking has beaten Heston Blumenthal's Fat Duck, the Roux brothers' Waterside Inn and Marcus Wareing at the Berkeley Hotel into cocked hats.

Gidleigh Park's à la carte menu (an expensive, though not ruinous, treat at £99 for three courses, plus coffee and petits fours) is a dream of classic Anglo-French cooking, in which the local provenance of the ingredients is emphasised like a mantra: Brixham scallops, Devon quail, Cornish seabass, Waddeton pheasant, Dartmoor lamb. But with the boldness that marks the kitchen connoisseur, Caines's British dishes are jolted with electrical charges of other cuisines.

His Loch Duart salmon arrives with an international entourage of Oscietra caviar, soy, wasabi and Greek yoghurt. His poached Cornish seabass comes clad in mystic flavours of "Thai puree" with shitake mushrooms, and noodles with lemongrass foam. Of the many accompaniments to his saddle of venison, you know that he's thought long and hard about the "raisins soaked in jasmine tea".

You don't get this kind of experimentation with food from reading books, but from personal obsession. "Chefs," as he is fond of saying, "are just extreme foodies."

His path to success started rough, then went smooth, then extremely rough. He was born in Exeter in 1969, the son of an absent Caribbean father and a white British mother, but was given up for adoption. He was adopted at four weeks by the Caines, a white Exeter family with a son and three girls. Just a year earlier, Enoch Powell's anti-immigration "rivers of blood" speech in Birmingham had stirred up racial tensions in the country, but the baby Michael seems to have encountered no scarring prejudice. He is clearly fond of his adoptive parents.

"My mum and dad always told me that families are born in the heart, not the tummy," he says. "We were a very sociable family, so I had fun growing up." He helped his mother bake in the kitchen. His father grew his own fruit and vegetables in the family garden. His favourite treat when young was blackberry and apple crumble, with Bramley apples from the garden.

At 18, he attended Exeter Catering College. His flair and attention to detail were spotted early, and he won 1987 Student of the Year. There followed a spectacular rising curve of apprenticeships at head-spinningly grand locations – Grosvenor House Hotel, London, then Le Manoir aux Quat'Saisons with Raymond Blanc (about whom he says, "Raymond has been a dear friend and wonderful mentor; because he wasn't classically trained, he didn't come to cooking with any baggage and he taught me, like him, to have no boundaries when it comes to thinking about food"), then a stint in France with Bernard Loiseau in Saulieu and the master of technical precision, Joël Robuchon in Paris.

In 1994, urged by Blanc, Caines returned to England to be head chef at Gidleigh Park. The lovely dining room inside the Tudorbethan mansion in Chagford already had one Michelin star. It was a fabulous challenge for the pushy, 25-year-old Caines. But with his fancy pedigree of teachers and mentors, how could he possibly fail?

And then the roof fell in. Literally. In hindsight, Caines blames himself for working too hard. "I was working seven days a week, because it was a new job and we had few staff, and you want to make a good impression." One morning he got up to attend a christening, jumped in his new car and set off. He later recalled the heat of the day, and remembered music playing: "... I felt myself becoming more and more tired ... I missed the turning because I'd nodded off," he told BBC News. "My car drifted from the outside lane to the inside lane, and hit the barrier. As it did, the car rolled and turned over. It screeched down the central reservation and bounced off. The whole roof collapsed, and my right arm was ripped off. One thing I'll never forget is the screeching sound of the metal. I woke up and knew immediately what had happened. I screamed."

He was 25, newly established in a crucial, demanding job which necessitated the use of two hands, eight fingers, two thumbs, all the time, all day. And now, right at the start of his career, he was, professionally speaking, dead meat, washed up, mutilated.

A lesser man might have crumbled and for a while Caines wanted to give up. Then, at the hospital, just before they put him under anaesthetic, he asked, "Can you save my arm?" to which the anaesthetist replied, "I don't think we can." When he came round, the memory of this blunt appraisal spurred him, counter-intuitively, into action. "I immediately said, 'I want to carry on.' I didn't want to let this beat me. All the time I'd spent learning my trade, I wasn't about to give up without a fight. The accident made me incredibly focused on achieving."

That's an understatement. Caines had a prosthetic arm attached and was back in the kitchen at Gidleigh Park in two weeks, working a full head-chef stint in four weeks.

He became even more driven. He worked insane hours. Five years of hard graft later, he was on a skiing holiday (standing, with apt symbolism, on a mountain top) when he heard the news: the Michelin inspectors had given Gidleigh Park its second Michelin star. It spurred him further. In the same year, 1999, he founded Michael Caines restaurants. The first of the franchise was Michael Caines at the Royal Clarence in Exeter – his adoptive home.

Four years later, he formed a partnership with the businessman Andrew Brownsword: they established ABode Hotels featuring Caines restaurants in Exeter, Glasgow, Canterbury, Chester, Bath and Manchester, and installed his own trained chefs in the kitchens.

The chain, it must be said, has had its share of upsets. In the summer of 2009, the newspapers reported that the Caines restaurant in the ABode Hotel in Canterbury had received a one-star hygiene rating, indicating "a poor level of compliance with food safety legislation", that was lower than Canterbury's Age Concern Day Centre. Caines has been accused of "cashing in on his fame", though he has some way to go to overtake, say, Marco Pierre White in the diffusion stakes.

He has thrown himself into family matters. He became a patron of Families for Children, a fostering agency and makes inspirational speeches about the need for more volunteers.

Caines recently tracked down his natural father, from the Caribbean island of Dominica, and discovered that, with pleasing symmetry, he was a cook. He's also been in touch with his birth mother, though they have not met. He is expecting his third child in April – sibling to Joseph, eight, and Hope, five, by a former partner.

What does the future hold? Caines has appeared on television, on BBC2's The Great British Menu, on Saturday Kitchen on BBC1, and as a taskmaster on BBC1's Celebrity Masterchef. It seems only a matter of time before he's given his own show, on which to rhapsodise about his local butcher at Pipers Farm. "Devon has one of the best food larders in Europe," he recently told the Independent on Sunday. "It outstrips other counties in the UK for the diversity and quality of its produce, as well as the outstanding natural beauty of its landscape and coastline." You can hear TV producers, and the Wessex tourist board, rubbing their hands.

But nothing seems beyond the man who came back from the dead, minus an arm, forged an empire by persuading people to believe in him, and won the top prize. Woe betide anyone who says he's incapable of anything. "If somebody says I can't do it, that's like a red rag to a bull," says Caines. "Who says I can't do it?"

A life in brief

Born: Michael Andrew Caines in Exeter, Devon, 1969. Adopted.

Family: Has a son and daughter with his ex-partner.

Education: Attended Exeter Catering College, then trained under Raymond Blanc, Bernard Loiseau and Joël Robuchon.

Career: In 1994, became head chef at Gidleigh Park. Awarded two Michelin stars. Has co-founded a series of boutique hotels. Gidleigh Park named the UK's best all-round restaurant by Harden's Restaurant Guide for the second year running.

He says: "Cooking is my passion. I love it and I can never see not being in the kitchens."

They say: "He's very much at the entrepreneurial end of his generation, maintaining standards at Gidleigh while expanding his own brand."

Peter Harden

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks