Nicholas Witchell has been reporting on the Royal Family for 15 years - wouldn't he rather swap the front of the Palace for the front line?

Witchell is every inch the royal guy – a model of diplomacy and discretion shuttling between palaces, walkabouts and occasional scandals. Does such commitment to a singular specialism explain why he views his career trajectory as flatter than Jeremy Paxman's, his one-time understudy?

Nicholas Witchell is not talking about the Queen when he recalls the incident which, along with an icy encounter with her eldest son, has come to define his career in broadcasting. "I lowered myself gently astride the dear lady," he says. "You could hear all these muffled cries and groans. I think it came as a shock to us both."

It came as a shock, too, to poor Sue Lawley, who had to read the headlines while Witchell wrestled a gay rights protester under the desk beside her, clamping his hand against her mouth. A second woman had also invaded the studio at the swing of the final bong, handcuffing herself to the camera. It wobbled slightly as Lawley kept going. 'BEEB MAN SITS ON LESBIAN', the Mirror's front page screamed the next day.

It was 1988 and Witchell was on top of his game. Four years earlier – and 30 years ago this September – the flame-haired reporter, then barely out of his twenties, had been handed one of the most coveted swivel chairs at the BBC, for the launch of the Six O'Clock News with Lawley.

"The third presenter was a certain J Paxman," he recalls. Senior producers on the show, meanwhile, included Tony Hall and Mark Damazer. "One is the Director-General and the other went on to be controller of Radio 4. Sue was the best news broadcaster the BBC has produced... and then there was me.

"My career trajectory has sort of gone a bit like that over 30 years," Witchell says, drawing a flat line in the air. "Theirs have gone like that." He draws a steep, upwards curve.

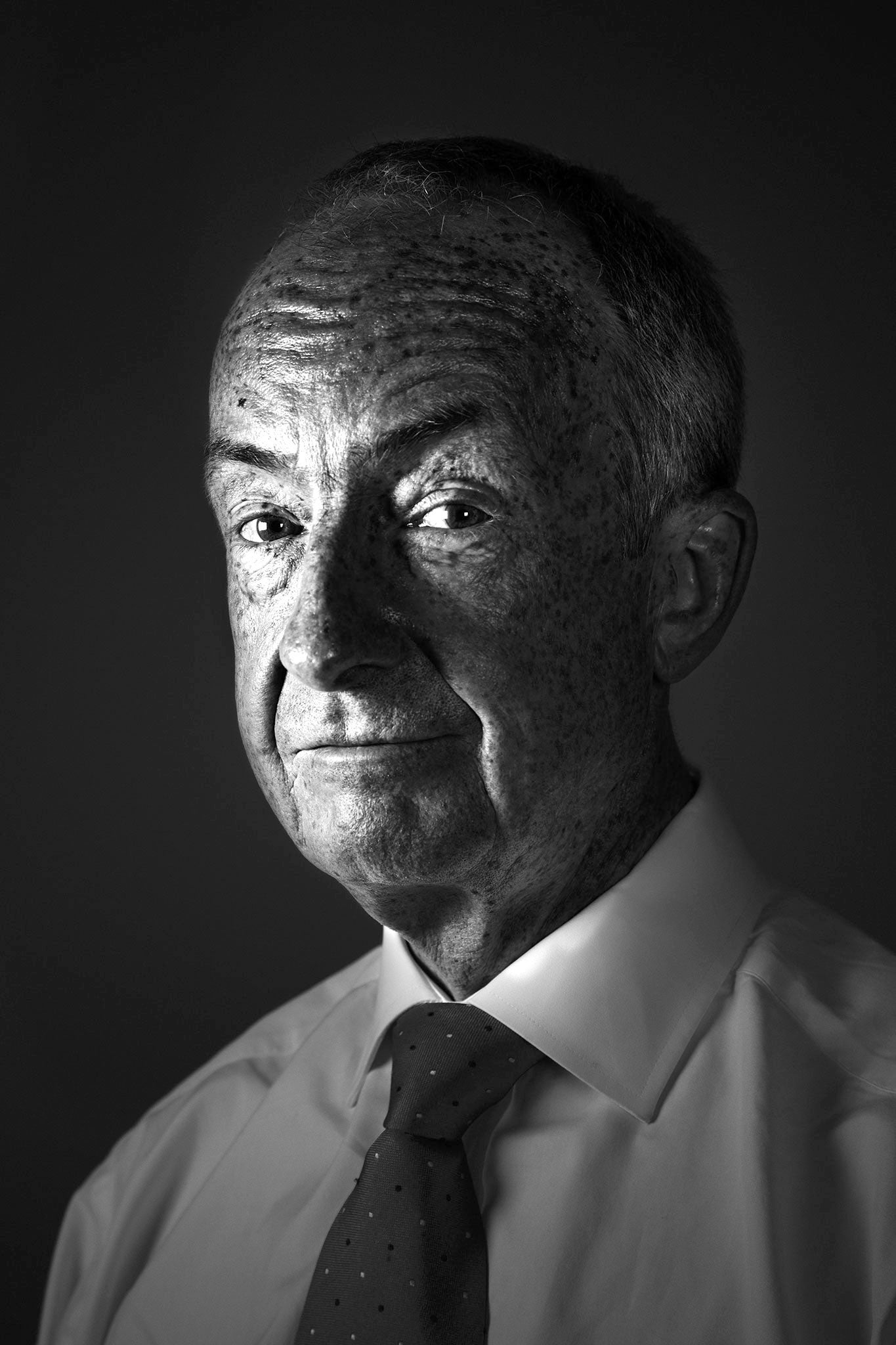

Witchell, who sits in a drab meeting area inside New Broadcasting House in central London, is now 60. His once luxuriant hair has largely given way to a freckle sea that reaches south towards his permanently raised eyebrows. He had taken some persuading to give his first national newspaper interview, and did not expect to be asked by this one. "I couldn't think why your readers would be interested in me," he says.

As those readers may know, The Independent tends to go small on royal news, which puts it at odds with the BBC's veteran royal correspondent. On the day the world first caught sight of Prince George last summer, for example, other British nationals devoted 73 pages between them to the arrival of a new heir. The Independent ran one story on page 12 – a search for republicans in Bucklebury, the Middleton family village.

But it is when viewed from a position of indifference that Witchell's career appears most intriguing. Why did a man who had become the face of news while covering and presenting some of the biggest stories of the Eighties and Nineties – Lockerbie, Zeebrugge, wars in Beirut, Lebanon and Bosnia – give it up to for 15 years of births, marriages and deaths? When he surveys the scrum outside the Lindo Wing, or describes the descent of a Duchess down some aeroplane steps in New Zealand, does he not yearn to be anywhere else?

First, some clarification. Witchell did not want the job, which he got in 1998, despite reports since that he had asked for it. "No, no, I certainly didn't," he says. "I declined several times but I think the third time that they asked me I figured it would be sensible to say yes." He is equally at pains to point out that his diplomatic duties have taken him to Baghdad as recently as 2010, as well as to the Chilcot and Leveson Inquiries into, respectively, the Iraq War and press ethics.

But, the odd diversion notwithstanding, Witchell is every inch the royal guy – a model of diplomacy and discretion shuttling between palaces, walkabouts and occasional scandals. Does such commitment to a singular specialism explain why he views his career trajectory as flatter than Paxman's, his one-time understudy?

"I've given completely the wrong impression," he says. "I was just trying to be engagingly self-deprecating." He goes on to defend his beat. "OK, so it's not war reporting but, whether your readers like it or not, this is an institution of some significance in this country. It's also a fascinating institution to have a peek at. And when it's a big story, it's a very, very big story and one that the BBC has to get absolutely right."

The BBC was accused of getting it wrong last year when royal hysteria centred on the door of a hospital in Paddington, despite a news vacuum ('WOMAN HAS BABY', Private Eye reported). Witchell has a reputation for being difficult and irritable, to the extent that his colleagues reportedly once nicknamed him 'the poisoned carrot' (more of which later). He is charming today but now lifts his narrow shoulders slightly.

"For the record, I didn't do a SINGLE piece for the domestic output until the day she was admitted to hospital – not one," he says. "I thought it was absurd the number of television stations, many of them from America, who were cranking out..." he thinks. Don't hold back, Nick. "...what was in many instances complete nonsense, day after day. Just vacuous, ridiculous nonsense."

Witchell recalls with disdain the clouds of hairspray that arrived over London with the preening US news anchors (he pronounces it "AN-korr", perhaps to emphasise his feeling). Yet the BBC, too, received ridicule and complaints about the scale of its coverage when the baby did appear. "I was criticised as everything from being sycophantic to subversive," he adds. "It's a difficult balance, because we have to appeal to Telegraph readers as well as Independent readers. But I think, with hindsight, there was too much coverage... we stuck with it for too long."

The sycophancy accusation could be levelled at many royal correspondents, whose accents and delivery seem to become more, well, royal, when they get the job. Witchell is so well-spoken that the popstar Ellie Goulding revealed last year she had tried to copy his voice to sound posher while growing up on a Hereford council estate. But the reporter – who grew up in Shropshire, went to Epsom College in Surrey, then Leeds University to study law – has sounded the same throughout, despite now having devoted almost half of his 38-year career to royal stories.

But is he a sycophant? Was he a fan of the monarchy before he took the job?

"Well I don't know that I'm going to answer that question," he says. "I think that there is universal respect for the Queen, but the essence of doing the job for the BBC is to keep your feelings out of it... and I think if you were talking to palace officials, they might say it's the BBC correspondents who are asking the difficult, challenging questions."

This brings us to the second incident for which, Witchell happily accepts, he will be remembered above all else. A week before Prince Charles married Camilla Parker Bowles in 2005, the three princes were perched in ski gear in front of the press in Klosters. Charles looked immediately pissed off. Witchell asked the trio how they were feeling about the wedding. Seconds later, Charles, oblivious to nearby microphones, muttered to William: "These bloody people. I can't bear that man. I mean, he's so awful, he really is."

"I thought, gosh, he's talking about me!" the correspondent says, remembering the discovery of the recording in the edit van. In the absence of anything else of interest to report, Witchell became the story. Has he received an apology? "There has never been an apology, and why should there be? He was probably quite right. You know, awful man. You could take the view it was the best thing that happened to me, because it showed that it is our job as BBC journalists to report fairly and accurately, but not to seek approval. We're not there to be liked."

Does Witchell like Charles? "He works terribly hard. There are all sorts of views about what he does, but it has to be said that he has attempted to make the most of his position as heir to the throne and do positive things. The Prince's Trust. Even the environment, which he's rather obsessed with."

If Charles still thinks Witchell is bloody awful he is not alone, at least judging by what little has been written about the reporter. He wonders if Private Eye came up with the poisoned carrot nickname, but he can't remember for sure. He has variously also been called a pint-sized prima donna, a ginger-haired cretin and an odious toad. Bit harsh?

"It's not pleasant to be caricatured in that way," he says of the carrot dig. "But some of it must be fair. I mean, what can I say, it's a pressurised environment. I think it all began when the Six O'Clock News started and I was young and possibly not as wise as possibly I am now and I rubbed some people up the wrong way."

Witchell's broader reputation is one for professionalism on and behind the camera, and privacy away from it. He used to have a pilot's licence and go diving, but won't be drawn on any extra-curricular activities today. He lives in London and has two teenage daughters from a previous marriage to Carolyn Stephenson, a jewellery designer: Arabella, a student at Bristol University, and Giselle.

He has now spent almost 40 years at the BBC, which he joined as a trainee straight after university (earlier, a youthful obsession with the Loch Ness Monster led him to write a book, The Loch Ness Story, about the creature, but Witchell says he never thinks about it now). His career covers more than half the history of BBC TV news itself, which marks its 60th anniversary today. On the morning after Paxman's last Newsnight appearance, does he feel ready to follow him out of Broadcasting House?

"Not with two teenage daughters to pay for," he says. He still enjoys his craft, he adds. He has half an eye on the deteriorating situation in Baghdad, and would leap on the chance to return. "But it's a little more difficult now to go somewhere difficult to get back from quickly if anything, you know, untowards happens," he adds, implicitly referring to certain ageing Windsors.

Witchell will spend the rest of the day preparing for the Queen's visit to Northern Ireland, where he cut his teeth as a young reporter. Then there are the royal finances to think about. Relaxed and engaging, yet still ambitious, he doesn't give the sense of a man caged by his duties. Is there a vegetable that might better be used to describe him now? "Well I'm certainly less carroty than I used to be," he says, glancing upwards. Has he softened over time? The ripened radish, perhaps. "I'll leave you to form your own judgment".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments