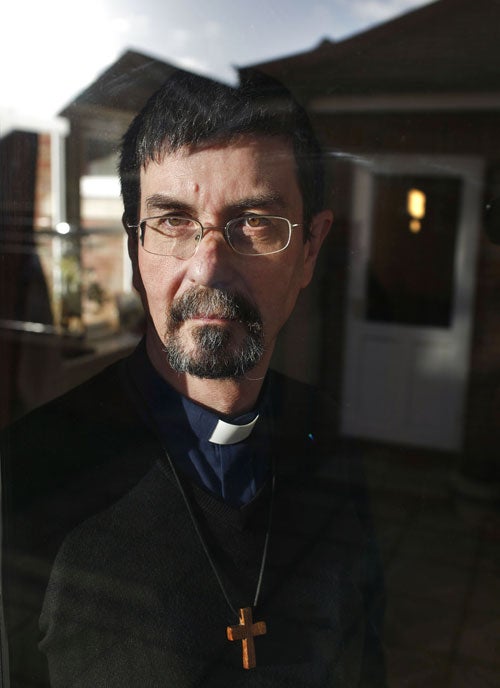

Rev Simon Boxall: 'I forgive my daughter's killers'

Vicar's child Rosimeiri Boxall leapt to her death from a third-floor window, at the age of 19, to escape the vicious attack of two teenage girls. They were jailed at the Old Bailey last week, but the Boxalls take no pleasure in that. Rachel Shields meets Rev Simon Boxall

To err is human; to forgive someone who killed your daughter is beyond comprehension. Yet that is exactly what the Rev Simon Boxall has done. It is the Christian way, he explains with almost disturbing equanimity. "I would have to force myself to be angry."

And yet, one feels, he should be angry: he could be forgiven the sin of wrath. In May last year, his 19-year-old daughter, Rosimeiri, was subjected to what a judge described as "ugly, vicious and repeated" bullying.

The court heard that two teenaged girls punched and slapped Rosimeiri in an argument over a boy. They pulled her hair and the pair sprayed air freshener in her face, calling her a "whore". They even encouraged three boys to watch and one to film the attack on a mobile phone as she cowered, trying to protect her head with her hands.

When she could take no more – at the hands of girls she once considered friends – she leapt to her death from a third-floor window in Blackheath, south London.

Last week, one of her tormentors, Hatice Can, who was only 13 at the time, was sentenced to eight years in prison. The other, Kemi Ajose, then 17, was detained indefinitely in a mental institution. Neither girl, now 15 and 19, showed a flicker of remorse. Not even for driving her to her death. As Rosimeiri lay dying in the street, the mobile phone footage records Can saying: "Serves you right, bitch."

Yet still, Mr Boxall insists that the whole nation needs to turn the other cheek, to reject what they see as Britain's "blame" culture, in which people are all too quick to reproach, but very slow to forgive.

Speaking exclusively to The Independent on Sunday at his home in south London last week, he explained how he and his wife came to terms with their daughter's death: "After the initial shock and numbness, we decided pretty much straight away to forgive."

And so the Boxalls refused to talk to the press after Can and Ajose were found guilty, but prior to sentencing, for fear that expressing their grief might encourage the trial judge to impose a harsher sentence: "We wanted absolutely everything to be fair, and didn't want to influence the judge in any way. If you go down the road of thinking that 'what happened to Rosimeiri wasn't fair, so why should I be fair', then it keeps getting passed on for ever, like a forged £10 note. It has to stop somewhere, someone has to absorb the loss, and we decided that it stops here."

He tails off, lost in the lights of the family's brightly decorated Christmas tree. He isn't wearing his dog-collar; the coffee and biscuits on the table aren't laid on for the usual procession of parishioners who seek his comfort and counsel. They are for him. And this time he is the one in need of comfort. Behind the fine china stands a photo of a teenager with a beaming smile and a dazzling white T-shirt, her Afro hair in cornrows,

Mr Boxall returns from his reverie and says that forgiving his daughter's killers has helped him to move on. He urges others who have suffered tragedies to do the same: "Anger only goes in on yourself. It creates bitterness within people, and means they can't get over the loss. It makes your heart cold."

His appearance – open-necked shirt, wire-rimmed glasses, carefully sculpted salt-and–pepper goatee – makes it easy to forget that he is a 54-year-old vicar. But he is in no doubt, and wants us to be in no doubt, that the strength to forgive comes from his faith: "It is in the prayer we read every day, 'Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who trespass against us.' I very much believe that if we don't forgive, we close ourselves up to God and other people." He sips black coffee, his hand rock steady.

A cross sits on the mantelpiece behind him, and – just in case there remains a shred of doubt – a tear-off calendar declares: "I believe in God."

He and his wife have taken strength from earthly sources, too: the stories of other bereaved parents who have managed the near impossible and forgiven their children's killers. They cite books such as Father, Forgive: The Forgotten "F" Word, written by Robin Oake after his son, a police officer, was killed while on duty, as particular comforts. Though, even here, they see the work of God.

While Rosimeirie's father has been quick to forgive her killers, he does not buy Hatice Can's defence: that her troubled upbringing meant that she too was "a victim of her background and circumstances". A rare glimpse of anger flickers when he considers it. "We are still responsible for what we do, and we have to realise that every choice has consequences," he says.

Nor did he ignore the lack of remorse shown by the two girls during their three-week trial; Can, who has a history of run-ins with the police, was seen smirking and joking just moments before she was sentenced. "The younger one didn't seem to show any remorse. It did make us sad. We've offered our forgiveness to the girls, but until a person shows remorse and repentance, they can't really receive our forgiveness. I don't think the elder one knew how to care, and the other one didn't want to care," he says. Despite this, last week he stood on the steps of the Old Bailey and offered his teenage daughter's unrepentant killers his whole-hearted forgiveness.

Faced with the Boxalls' compassion, some have wondered – perhaps unfairly – if they would have been as quick to pardon the killers if she had been their biological child. Rosimeiri – pronounced "Hosimary", and known to her family as "Hosi" – was adopted at the age of three from a children's home in Bagé, a small town in the south of Brazil in 1991. She had been abandoned by her alcoholic mother.

The Boxalls, who by this time had four sons, had been living in South America since moving there to work as missionaries in 1984. They wanted to give the child a better life. "She was quite a tomboy, but we needed pink sheets and wallpaper for the first time. The boys adored her.

"She didn't speak at all in the children's home, but she spoke both languages [Portuguese and English] fluently with us."

The family's modern, red-brick house, on a vast estate in Thamesmead, is littered with reminders of the 20 years that the family spent in Rio. Two large prints show the glittering lights of Rio, with its Copacabana beach and Sugar Loaf Mountain; while the city's less glamorous side is depicted in a small oil painting showing the higgledy-piggledy houses of the favelas.

The couple returned to England in 2005, bringing 16-year-old Hosi and their 17-year-old son Nathan with them. If adjusting to life in Britain was difficult for all the family after living abroad for 20 years, it was especially challenging for Hosi, who was enrolled at the local Plumstead Manor School. "She did struggle at school," admits her mother, Rachel. "I don't know what it was, but she struggled academically, and she wouldn't have been in the top half of any class."

While the trial judge commended the Boxalls for giving Rosimeiri "a wonderful chance in life", many of the reports after her death emphasised the fact that the 19-year-old had moved out of her parents' home and into temporary accommodation, mixing with a social circle quite different from that of her close-knit Christian family and seemingly distancing herself them.

Mr Boxall dismisses suggestions that he had lost contact with his daughter, insisting that any problems were just normal teenage rebellion: "We'd spoken to her two days before her death and she sounded very happy. She left home at 18, just as lots of teenagers do. She lived with friends and moved around. When she left school, we tried to help her find a job. My father was in the Army and we just said, 'Would you like to join the Army?' And she seemed to be enthusiastic. She looked into it and put a poster of the exercises on her wall. It gave her a focus, for a while. We also suggested hairdressing amongst other things."

Now, instead of worrying what path Rosimeiri will take, they are left to face the grim reality that she is gone, and that endless possibilities have gone with her.

As if this were not bitter enough, her future was destroyed by girls she had once called friends: at least one had met her parents and been welcomed into the Boxalls' family home. "I took the older girl [Ajose] home once, and she was talking about the holidays she had with her family to Butlins, and the fun they had," says the parish priest, sadly. And, for a second, he could be mourning either his daughter or her tormentor: "She's lost that now, that innocence."

Rosi and her killers

Rosimeiri Boxall, 19

Adopted by the Boxalls when aged three, Brazilian Rosi, above left, had been living in England since 2005. She initially attended Plumstead Manor School in south London but dropped out and moved out of the family home 18 months before her death.

Oluwakemi Ajose, 19

Previously best friends with Rosi, the teenager from Charlton, south-east London – known as Kemi – has a history of mental health problems. While in prison, Ajose, above centre, encouraged vulnerable inmates to commit suicide using their bedsheets.

Hatice Can, 15

Only 13 at the time of Rosi's death, she had been living with the other two girls at a flat in Blackheath. Can, above right, was seen standing over her friend's body, saying: "Serves you right, bitch."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks