Shaun Edwards: 'The tough times have just made me tougher'

The Brian Viner Interview: The Wales coach talks about his brother's death, his no-nonsense image and his desire to win the Six Nations

If there is a single cast-iron certainty about television coverage of the forthcoming Six Nations tournament, it is that during Wales matches the cameras will find Warren Gatland and Shaun Edwards, the Kiwi head coach and his part-time Lancastrian assistant, sitting next to each other high up in the stand, one with a face like thunder and the other looking slightly crosser. Even when their men are playing well, they are international rugby union's answer to Statler and Waldorf, The Muppet Show's resident grumps, and rarely can a dressing room seem less like a players' sanctuary than when one or other of them is venting his discontent.

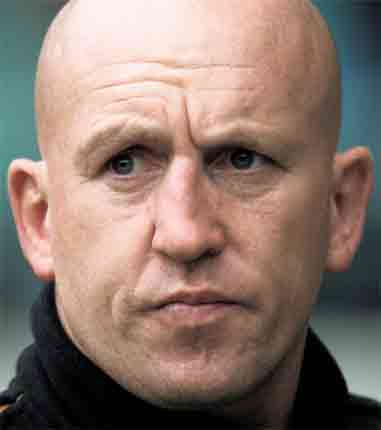

Edwards, the rugby league legend who played in all of Wigan's eight consecutive Challenge Cup victories, and who six years ago succeeded Gatland as head coach at Wasps, remains the hardest of hard men, his basilisk stare disconcerting even across a table in a room at the Wasps training ground in west London. But it's not intended to intimidate, it's simply what he looks like when he's concentrating on a question, or, I suppose, a rugby match. And when he's talking he is both animated and generously candid, never more so than when reflecting on the death of his beloved younger brother, Billie-Joe, in a car crash in 2003.

The last time we met, three years ago, he also spoke movingly of his fascination with the First World War. I ask whether he still reads up on the harrowing stories of the trenches, and whether he uses that knowledge as a way of putting sport in perspective. He sighs. "Well, it's horrific, isn't it, what they went through. And losing my brother too, compared with things like that sport is inconsequential. But it's still the passion of my life, so maybe I shouldn't say inconsequential, maybe that demeans sport..."

It wouldn't do for the most illustrious member of Wigan's celebrated Edwards family to say anything that might demean sport. After all, Billie-Joe was a promising rugby league player and so was their father, Jack, just 24 when, in 1963, his career at Warrington was abruptly ended by a crippling spinal injury that plagues him still. "He suffers in silence," Edwards says. "And he's still struggling with my brother's loss, to be honest. It does slightly diminish as time goes by, but then for me it's nothing compared with what my parents have been through. No mother and father should ever have to bury a son."

A fleeting silence is broken by the sound of high jinks in the gym downstairs, a rather timely interruption, for it was the distractions of his job as backs coach at Wasps that carried him through his grief. "You don't want time on your own to ponder, so it was helpful, especially having Lawrence [Dallaglio] here. There was real empathy, because he'd lost his sister [in the 1989 Marchioness river-boat disaster]. It's part of the reason we're very close."

I ask Edwards whether Dallaglio ever gives him stick for plying the international side of his trade on the other side of the Severn Bridge, although of course he could have been in the England camp had the red -rose hierarchy been smarter three years ago (allowing him to join the Welsh was considered nothing less than "a crime" by his former protégé at Wasps, Matt Dawson).

"No, not really. Anyway, if you're in the coaching set-up with England at the moment then you can't do a club job." Would he fancy being an international head coach one day? "You never know. But I'm very happy doing what I'm doing. I've never wanted to be a director of rugby, dealing with contracts, sacking people. My passion is helping players become better."

What, though, are his ambitions for himself? There is a long, long pause. "I would love to give the [Wasps] owner, Steve Hayes, a trophy. I'd love to say 'here, that's for you, pal'. Because he pays the wages and he's taken a few losses along the way, as [former owner] Chris Wright did, but he won things. And I'd like to win the Six Nations with Wales. And I'd like to make the Welsh nation proud at World Cup time."

It is characteristic of Edwards that his ambitions are all about helping others achieve theirs, entirely consistent with the man who, when he retired as a player, spent a summer working in a shelter for the homeless in north London, run by the Sisters of Mercy. "But I haven't been for a long time now, too busy and probably a bit too lazy," he says when I mention his charitable work. "I used to help on the soup kitchens at night. Some of the lads could be a bit tetchy at times, so I think the sisters were pleased I was there. But enough has been made of it. Don't write too much about that..."

I can't imagine what "a bit tetchy" is a euphemism for, but anyway, let's turn to a subject he is happier to discuss: Wales v England at the Millennium Stadium a fortnight today. "It's obviously a pivotal game and we're sure we can do well. We didn't get battered by any of the Tri-Nations teams in the autumn internationals, though we can improve our turnover defence. The try of the series was [Chris] Ashton's try [for England] against Australia, and that was from a turnover ball, when the defence wasn't set. We need to improve that, and also improve our kicking game. I want us to compete in the Six Nations and particularly the World Cup." A swig of water. "No, not compete, win."

Edwards has never been to a World Cup. He was, however, on Ian McGeechan's staff on the 2009 Lions tour to South Africa, one of the most memorable yet frustrating experiences of his coaching career. "It does my head in even now. It will haunt me until my dying day that we didn't win."

Still, learning from defeat has always been a cornerstone of his coaching philosophy, albeit a cornerstone that he has been leaning on more than he'd like in the last couple of seasons, with neither Wales nor Wasps enjoying the success of three or four years ago.

"But Wayne Bennett, the greatest rugby league coach in history, told me that if you're in this game for long enough you'll experience everything," he says, with a smile. "At one stage of his career he went seven years without winning anything. So maybe my expectations are unrealistic. If I'd known at the start of my coaching career that I'd have six years of winning trophies, then a Grand Slam, then a Lions tour, I'd have done double somersaults... if my knee had let me. Yes, there have been some tough times recently, but tough times make tougher men. Look at Alex Ferguson. Even he hasn't had continual success."

How easy is it, though, to trust in coaching methods when they're not yielding wins every weekend? "I question my methods and tactics each and every day. Like lots of coaches, I'm always looking at different methods, different motivational techniques. I'm a big fan of American football, a big boxing fan. I'm a great admirer of [the boxing trainer] Freddie Roach, who trained my friend Steve Collins and has done a great job with Amir Khan. I like the way his fighters fight. I'd love to go to his gym, hang around for a week or so."

This appetite for learning was not quite so prodigious at St John Fisher high school, Wigan, not that it mattered much in a boy who captained English schools in both codes of rugby, and broke all schoolboy records by signing for Wigan on his 17th birthday for £35,000. "History was the only subject I took much notice of at school," he recalls, "and funnily enough it's my son's best subject too."

His son James, by the M People singer Heather Small, is on a rugby scholarship at Harrow. I confess to being slightly startled when he tells me this; the tough-as-nails Wiganer, so in touch with his working-class roots that during the 1984 miners' strike he taped over the British Coal logo on his shirt, with a son at the school of Lord Byron and, for that matter, Margaret Thatcher's son Mark. Yet the incongruity of it gives Edwards nothing but pleasure. "My father and mother came down to watch James play, and as my father said, the facilities there are like heaven for a young man, heaven on earth."

Indeed, and yet his own stellar playing career was forged in the narrow terraced streets of Wigan. Does he worry that, however heavenly the facilities at Harrow, James might be missing something less tangible but more valuable in his sporting education? "Well, I had it tougher in some ways but it's a daunting thing leaving home at 13, you know. In fact, I remember Fraser Waters telling me he left home at eight. So they have it tougher in different ways. When I moved out of my mum's house, I moved about 60 yards down the street." How old was he? "Twenty-two," he says, with a bellow of laughter.

"But I know what you mean," he adds. "And it's funny seeing all that privilege at Harrow, because when I broke my cheekbone at Wembley [in the 1990 Challenge Cup final, playing on through the pain] I went to hospital after the game for surgery, and the hospital was in Harrow-on-the-Hill. I remember going for a walk and ringing my mother afterwards. I said, 'it's a different world here. There are lads with straw hats on.' And 20 years later my own son's going there. It's funny where life's twists and turns take you."

His own more literal twists and turns were once applied to the round ball as well as the oval ball; as a footballer he was a nippy winger with Wigan schoolboys. "But the coach gave up on me when he saw me practising my goalkicking with a soccer ball," he says, admitting that he doesn't really follow Wigan Athletic, or any football team. "But I admire the players. They're tremendous athletes with great stamina. People who say it's a soft game don't know what they're talking about. Actually, I think it's easier to hurt someone in soccer, if you want to, because you can go in from behind."

All the same, it must drive him mad, this hard nut who played through a cup final with a broken cheekbone, when he sees Premier League footballers, after gossamer contact, go to ground as if they've been shot.

"Well, yeah, that's a bit disappointing. I think I did it once, for Great Britain against Australia [in the 1994 Test series]. I'd got sent off in the first Test, for putting in a pretty hefty shot on Bradley Clyde, and in the third Test I knew they'd be coming for me. About six minutes in I passed the ball and Dean Pay followed through with his elbow. Luckily I'd been doing some sparring with [his Wigan team-mate Va'aiga] Tuigamala which had helped my reactions, because I knew that if Tuigamala hit me I'd end up on the roof. So the elbow just glanced off me. But he'd been trying to break my jaw. So I stayed down, trying to get as much out of the ref as possible."

And with that, my time is up. We shake hands, Edwards still looking faintly embarrassed by that solitary act of simulation in 17 years of making, and sustaining, bone-crunching tackles, and I can't help reflecting as I head out of west London that someone should introduce him to Didier Drogba.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks