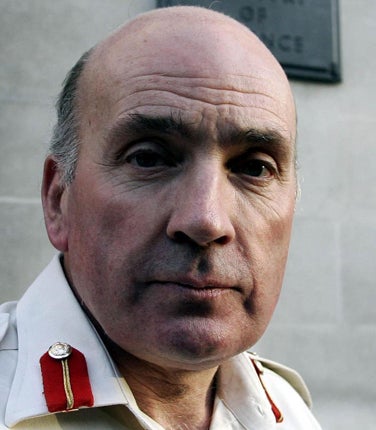

Soldier's soldier: General Sir Richard Dannatt

The outgoing Chief of General Staff has done much to expose the poor pay and conditions in the Army and raise public sympathy

General Sir Richard Dannatt is finishing his three-year stint as the head of the British Army in as tempestuous a manner as he began, with a political firestorm raging around him, and very much the centre of the story amid the continuing grim news from Afghanistan.

Yesterday, as he arrived back in the country after liberally lobbing verbal hand grenades about lack of troops and helicopters during his valedictory tour of Afghanistan, the recurring name in ministerial briefings was "Dannatt". The Ministry of Defence (MoD) press office, meanwhile, was frantically sending out "clarifications" about the numerous statements from the general.

The combustible nature of Sir Richard's tenure as Chief of General Staff came as something of a surprise. He arrived in the job with a reputation for being a safe pair of hands and somewhat reserved – a very different personality from his predecessor, General Sir Mike Jackson, the man of the hour in Kosovo, and someone with a very colourful public profile.

However, while General Jackson had built up a quite a fearsome reputation as a soldier, he was careful, once in office, to vent his frustrations in private rather than public. In his first week in the new role, in his first official meeting with defence and diplomatic correspondents, General Dannatt was keen to speak about poor pay and conditions being endured by soldiers, something which was to become a recurring theme. That got a certain amount of desired publicity without too much fuss. His next intervention in the media, however, was to cause ructions, and set the pattern for the future. He is said to have insisted that his first major newspaper interview should be with the Daily Mail, a publication which does not engender much warmth in the military. And, when it took place, his comments about the conduct of the Iraq war, and, again, the neglect of the forces, could not be seen as anything but an attack on the policy of Tony Blair's government. Downing Street, not surprisingly, was not amused.

Whether General Dannatt actually realised the effect his words would have is a matter of conjecture. His friends say he was surprised by the publicity and the resultant furore. The contentious passage was apparently buried away in the middle of a long interview, but spotted by an enterprising member of the news desk and put on the front page. Senior civil servants in the MoD, however, insist that Sir Richard knew exactly what he was doing and had, in fact, a member of his staff monitor the news once the story broke.

General Dannatt is not actually a novice in Whitehall. After distinguished service with the Green Howards – during which he won the Military Cross in Northern Ireland at the age of just 22 – he had been a military assistant in the private offices of several defence ministers and held other office jobs in the MoD. His bluffness, say associates, is at times a cover for a shrewd strategist who knows how to conduct a long campaign in bureaucratic battlefields.

The main focus of this campaign, it soon became clear, was the welfare of the members of the armed forces. The general ventured into areas where other senior officers had been careful about treading, discoursing on public finance, stressing that the Government was spending 29 per cent on social services while devoting just 5 per cent to defence, pointing out that a soldier often earned less than a traffic warden. "Is £1,150 take-home pay for a month's fighting in Helmand province sufficient?" he asked. The so-called military covenant, the understanding that the nation would care for its armed forces in return for the sacrifices they make, was now "out of kilter".

The campaign was a sure-fire winner. Vast sections of the public may have been against the Iraq war, confused and sceptical about being in Afghanistan, but there was a deep pool of sympathy for the men who have been sent to fight in the nation's name.

The Government, on the other hand, was in a no-win situation. It could hardly criticise what General Dannatt was saying. The mantra was "everything that can be done will be done"; all "funding necessary will be made available". However, as it became clear to ministers that they would get scant credit for putting in more money, and nothing they said seemed to satisfy Sir Richard, the words began to be spoken through increasingly gritted teeth. Their revenge, it is often said, was to stop Sir Richard from succeeding the head of the armed forces, Air Chief Marshal Sir Jock Stirrup. However, although this is a convenient argument, there are doubts as to whether Dannatt would, in fact, have got the job, even if he had been less troublesome.

In the Army there was gratitude that, especially among the junior ranks, here was a chief who was on their side and had not followed the path of predecessors who had grown distant as they hobnobbed with those in power. The various informal websites used by forces personnel were full of praise.

However, over time, mutterings began within the military about Dannatt. One result of the general's continuing confrontation with the Government, it was claimed, was that the Royal Navy got two aircraft carriers, the RAF got its fast jets, while the Army got just 10 per cent of the procurement budget.

There was also the feeling that although Sir Richard undoubtedly had done a great job in raising the nation's perception of the forces, where, exactly, it was asked, was the greater vision? What was the geopolitical overview on Iraq and Afghanistan? How does one react to resurgent and combative Russian power?

Then there was Sir Richard's deep Christian beliefs and the regret that this was shared by a dwindling number in modern Britain. "It is said that we live in a post-Christian society," he said. "I think that it is a great shame. The broader Judaeo-Christian tradition has underpinned British society. It underpins the British Army. British society has always been embedded in Christian values. When I see the Islamist threat in this country I hope it doesn't make undue progress because there is a moral and spiritual vacuum in this country. Our society has always been embedded in Christian values; once you have pulled the anchor up there is a danger that our society moves with the prevailing wind."

Sir Richard insisted that his Christianity was not proselytising and, in fact, he wanted to ensure that greater sensitivity should be shown towards different religions. On Iraq, he said, "We are in a Muslim country and Muslims' views of foreigners in their country are quite clear. As a foreigner, you can be welcomed by being invited in a country, but we weren't invited ... The military campaign we fought in 2003 effectively kicked the door in." But his repeated public affirmations of faith did cause concern. "We have enough bloody jihadists already in the 'war on terror' without having another one on our side," said one senior officer. "We have already had Bush and Blair praying together before invading Iraq; the CGS going on in this way does not help when we are fighting our wars in Muslim countries, promoting, although we would not put it in so many words, secularism."

After leaving the Army next month, General Dannatt will become chairman of RUSI (Royal United Services Institute) and Constable of the Tower of London. There are also rumours that he may join David Cameron's government if the Tories win the next election.

It has been noticed that as he approaches retirement Sir Richard is concerned as to what his legacy will be. Indeed, he asks people that directly. The consensus in defence circles is that the general has played a key role in gaining the nation's sympathy for the forces and that he has been steadfast in standing up to politicians on behalf of his troops. The corollary is he leaves behind a corrosive landscape in the relationship between the Government and the military, and his public campaigns have raised important questions to be answered on just how far commanders should stray into the political sphere.

A life in brief

Born: Chelmsford, Essex, 23 December 1950

Family: Married in 1977; three sons and one daughter

Education: Felsted School and St Lawrence College, Ramsgate, then Hatfield College, Durham University, where he was elected President of Durham Union Society and received a BA(Hons) in Economic History

Career: Commissioned to the Green Howards Regiment in 1971, he later served in the 1st Battalion in Northern Ireland (where he was awarded the Military Cross), Cyprus and Germany. From 1994-6 he commanded 4th Armoured Brigade in Germany and Bosnia, then British forces in Kosovo. From 2001-2 he was Assistant Chief of the General Staff at the Ministry of Defence before taking command of Nato's Allied Rapid Reaction Corps. In March 2005 he was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Land Command. He was made Chief of the General Staff in August 2006, replacing General Sir Mike Jackson. Next month he hands over to General Sir David Richards.

He says: "British society has always been embedded in Christian values; once you have pulled the anchor up there is a danger that our society moves with the prevailing wind."

They say: His outspoken comments imply a constitutional change, "namely that the armed services in our democracy will interfere with the correct role of the government." – David Blunkett, former Home Secretary

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks