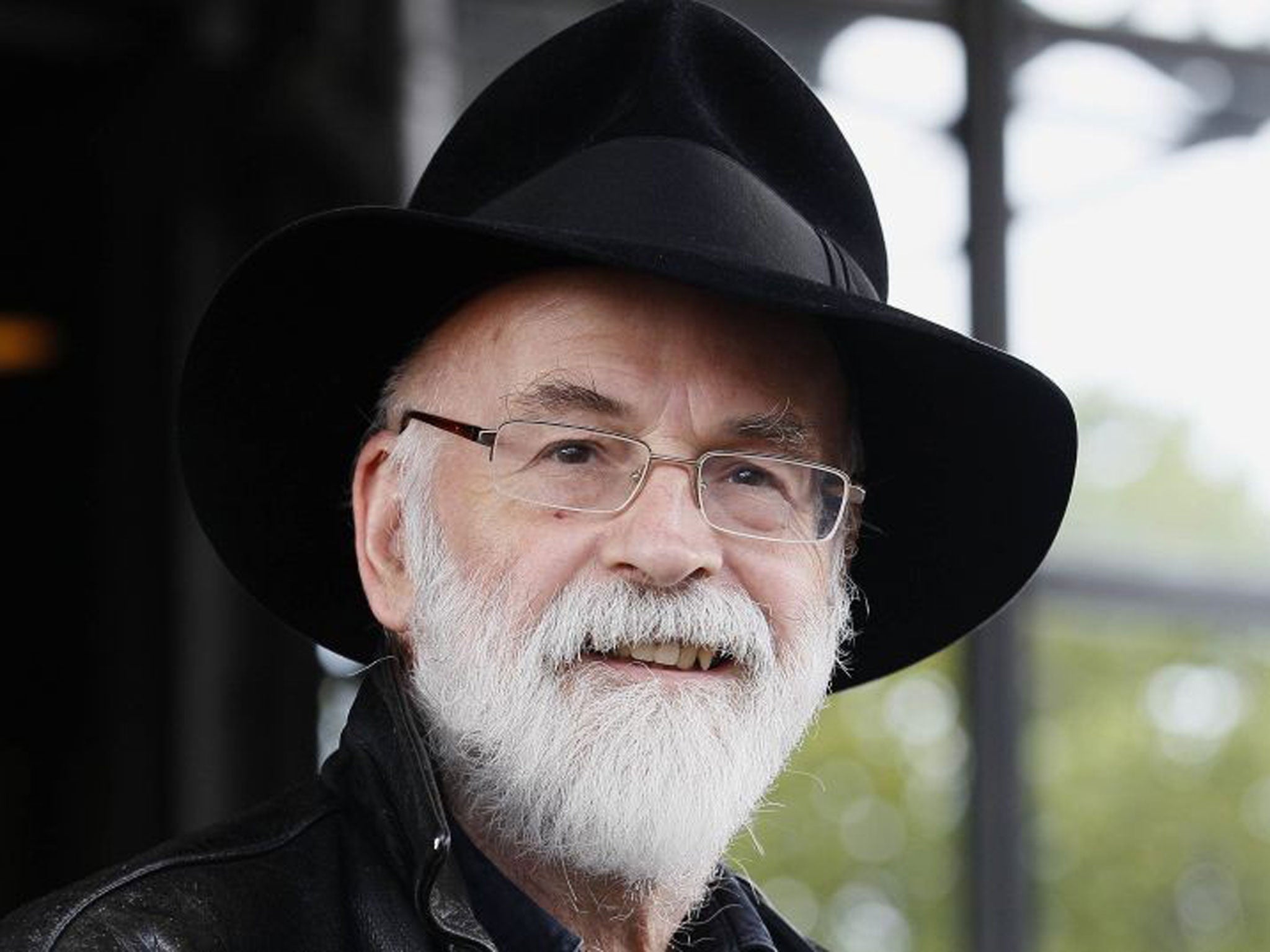

Sir Terry Pratchett: Author’s Discworld series of novels sold millions and he faced early-onset Alzheimer’s with courage and wit

Pratchett was one of the most prolific and successful authors of his generation

Discworld is not unlike our own world – except for the fact that it is a flat disc carried on the back of four elephants which ride a giant turtle through space. It was created by Sir Terry Pratchett, whose series of comic fantasy novels made him one of the most prolific and successful authors of his generation. He sold more than sold more than 80 million books and was translated into more than 30 languages. By the turn of the century only JK Rowling was beating him to the title of Britain’s most-read author – and he had one title she didn’t, that of Britain’s most shoplifted novelist.

His books, while always lively and humorous, generally had a serious, satirical element, and in many of them he dealt with philosophical and ethical questions and arguments, touching on such subjects as religion, consciousness and international relations. Among the interwoven storylines there are parodies of Shakespeare, Tolkien and Lovecraft, as well as pastiches of the cliches of fantasy literature. He first aired the concept of a flat world in his debut novel, The Carpet People, which was published in 1971; 12 years later came the first Discworld offering, The Colour of Magic. It was followed by 40 more, with the last one, The Shepherd’s Crown, appearing posthumously in 2015.

But by then his health was in decline. In August 2007 he had been misdiagnosed as having suffered a stroke, but four months later he announced he had a rare form of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease which, he said, “lay behind this year’s phantom stroke”. Calling the diagnosis “an embuggerance”, he wrote: “We are taking it fairly philosophically down here and possibly with a mild optimism. I would just like to draw attention to everyone reading the above that this should be interpreted as ‘I am not dead’... I know it’s a very human thing to say, ‘Is there anything I can do?’ but in this case I would only entertain offers from very high-end experts in brain chemistry.”

The following March he announced he was donating £500,000 to the Alzheimer’s Research UK, and he devoted much of the rest of his life to raising awareness of dementia and the urgent need for more research. He also explored the case for assisted suicide in an acclaimed TV documentary. “Either we have control of our lives, or we do not,” he said.

Terence David John Pratchett was born in 1948 in Beaconsfield. An only child, he passed his 11-plus and went to Wycombe Technical High School where he published his first short story, The Hades Business, in the school magazine. He was, he said, “a nondescript student”, and in his Who’s Who entry he credited part of his education to Beaconsfield public library. With a serious schoolboy interest in astronomy, he became a voracious reader of science fiction.

He worked for the Bucks Free Press newspaper after leaving school, then after various other jobs in journalism he became press officer for the Central Electricity Generation Board in 1983. He left the CEGB in 1987 after finishing his fourth Discworld novel.

His breakthrough had come in 1968, when he interviewed Peter Bander van Duren, director of a small publishing company. Pratchett mentioned he had written a manuscript, The Carpet People, and Bander van Duren and his business partner Colin Smythe published the book in 1971, with illustrations by Pratchett.

After he began to write full-time his sales increased rapidly and he became a familiar figure at the top of the bestseller lists. He was the top-selling and highest-earning author in 1996, and in 1998 he was awarded an OBE for services to literature. He responded: “I suspect the ‘services to literature’ consisted of refraining from trying to write any.”

He was knighted in 2009, and outside Buckingham Palace he took the opportunity to declare that bankers’ bonuses should be spent helping to treat dementia patients.

“The thing about Alzheimer’s is there are few families that haven’t been touched by the disease,” he said. “People come up to me and talk about it and burst into tears, there’s far more awareness about it – and that was really what I hoped was going to happen.

“Everybody thinks the government should be doing more about everything, but just think how many of the bonuses which are quite rightly being dragged off certain people, just think to what good causes they could be put – wouldn’t that be a lovely thought?”

He had a unique personal style, with his big black hats, which was once described as “more that of urban cowboy than city gent”. Asked if it was true he never took his hat off, he replied: “I do take it off sometimes because how else is a man to shower?” He was an avid computer games player and collaborated on several games adaptations of his books.

In 2001 he won the annual Carnegie Medal for The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, the first Discworld book aimed at children, and received the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 2010. He had many other awards, including the British Books Award as Fantasy and Scientific Author of the Year in 1994. He was also awarded honorary doctorates by the universities of Warwick, Portsmouth, Bath and Bristol. His concern for the future of civilisation prompted him to instal solar cells at his house near Salisbury, and his childhood interest in astronomy led him to build an observatory in his garden.

He died at home “with his cat sleeping on his bed, surrounded by his family”, said his publisher, Larry Finlay. He had faced his illness with typical humour and stoicism. “There is a rumour going around that I have found God,” he said the year after his diagnosis. “I think this is unlikely because I have enough difficulty finding my keys.”

Terence David John Pratchett, author: born 28 April 1948; OBE in 1998, knighthood in 2009; married Lyn Purves (one daughter); died 12 March 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks