Richard Adams obituary: author of the bestselling novel 'Watership Down'

The idea that an epic adventure about a bunch of rabbits written by a career civil servant could become a world bestseller would, on the face of it, seem unlikely. Certainly, that’s what the three literary agents and four publishers who turned down Richard Adams’s manuscript of Watership Down must have thought. But within weeks of its eventual publication in 1972, Watership Down was a massive success among adults and children, an instant classic to be ranked alongside the anthropomorphic fiction of such authors as Rudyard Kipling, JRR Tolkien, Lewis Carroll and Kenneth Graham.

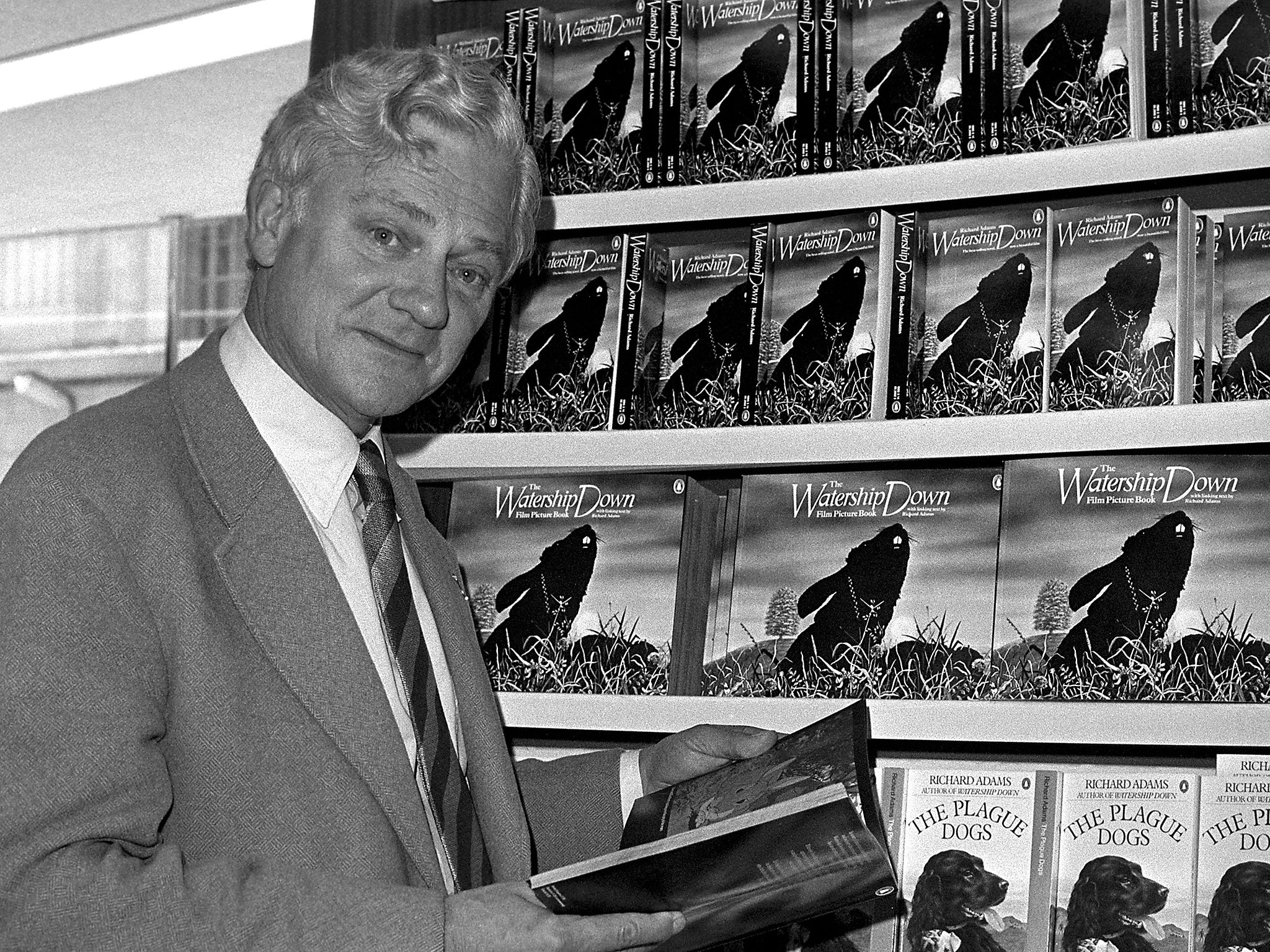

Although Adams’s next two novels, Shardik and The Plague Dogs, sold very well, Watership Down’s success overshadowed everything else he ever wrote and towards the end of his life he returned to the rabbit’s odyssey in a kind of sequel, Tales from Watership Down. He was born in 1920 in Newbury. His father was the surgeon Evelyn George Beadon, who with Richard’s mother Rose lived in a spacious house with acres of garden in the Berkshire countryside that became the land of Watership Down. Although Adams had an elder sister and brother, they were so much older that he spent a lot of time on his own, “a solitary little boy with an enormous fantasy life”, as he described himself later. He also recalled that his favourites among the stories his father read to the children were the Doctor Dolittle stories by Hugh Lofting.

Curiously, Adams shared a class at prep school with AA Milne’s son Christopher, the real-life inspiration for Christopher Robin. He was educated at Bradfield College and in 1938 went to Worcester College, Oxford University to study history. When war broke out in 1939 he joined the British Airborne Forces. He returned to Oxford at the end of the war and received his MA in modern history in 1948. At some point in these early years he underwent Jungian psychoanalysis.

He married Barbara Acland in 1949, when he was 29; she later became a lecturer and writer on chinaware. The year before, he had joined the Civil Service, where he remained until he took an early retirement after the success of Watership Down. He began in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, but was moved from department to department every four or five years. By the time he came to write Watership Down in 1970 he was an assistant secretary in the Department of the Environment’s clean air section.

He and Barbara had their daughters, Juliet and Rosamond, quite late in life, and it was thanks to the girls’ pleasure in hearing stories that Watership Down came about. Determined to interest the girls in Shakespeare, their parents took them to Stratford to see the RSC. The girls demanded a story for the five-hour car journey.

Adams, a great enthusiast for Greek literature, thought of Cassandra, cursed by Apollo always to prophesy the truth and never be believed. He applied this attribute to a rabbit called Fiver, who sees a field running with blood and warns his fellow rabbits that they must abandon their burrow and find somewhere else to live. The story developed from there.

Adams recalled later: “All the principal ingredients were extemporised off the top of my head. It wasn’t finished on the trip to Stratford. It continued on morning drives to school. It was about a fortnight before I finished telling it to them the first time.”

The girls suggested he should write it down but he said he had no time, until one night he was reading to them at bedtime. “It wasn’t a very good book. It jarred on me and I threw the book across the room and said, ‘I could write better than that myself.’ And the nine-year-old Juliet said very acidly, ‘Well, I wish you would, Daddy, instead of keeping on talking about it.’”

He spent two years writing Watership Down in the evenings after work. “I’d get home from work, have my supper, have a look at the nine o’clock news on television and then I’d get down to writing another bit. This sometimes went on until one in the morning. I thoroughly got the bit between my teeth.”

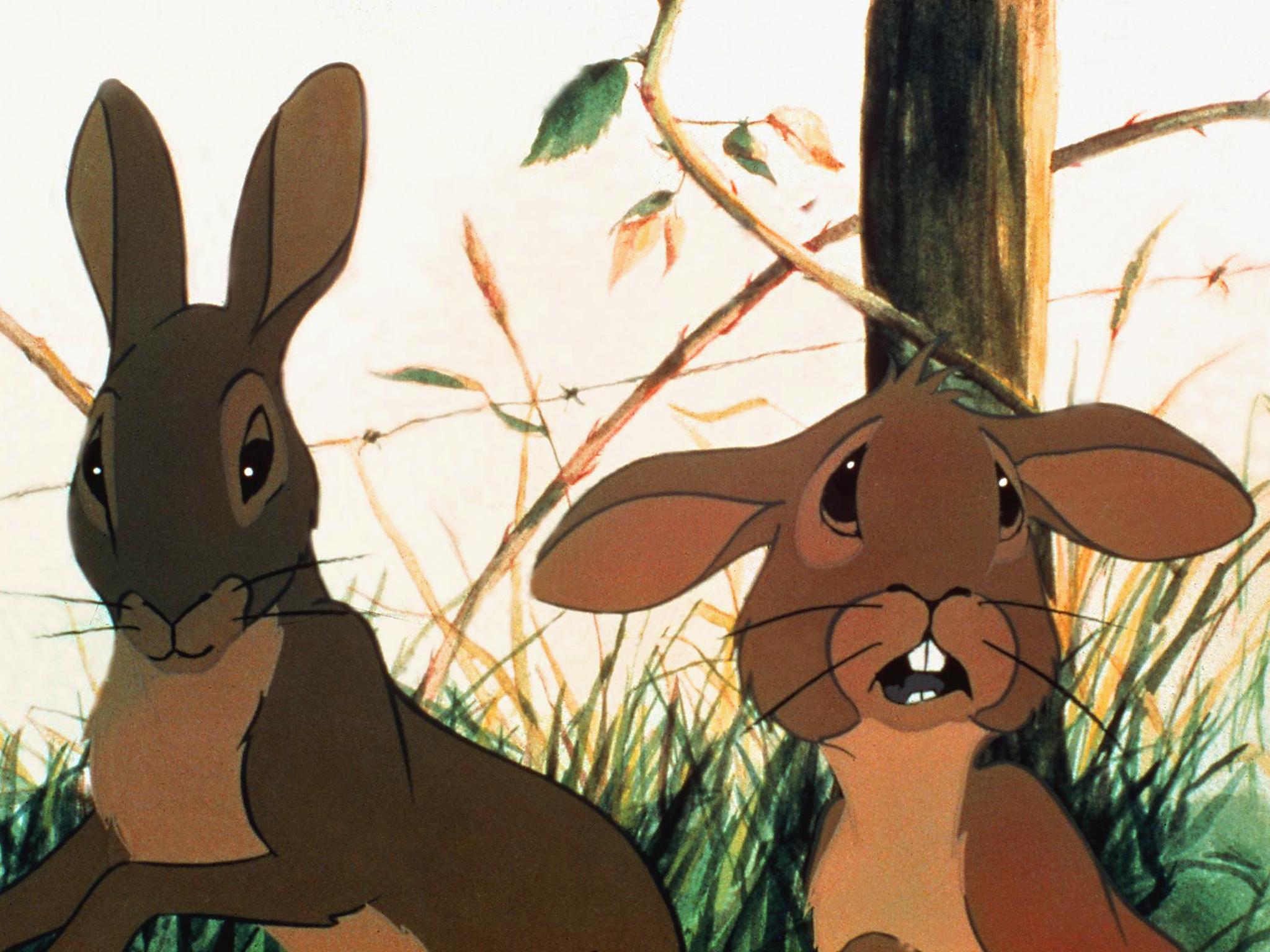

He took his basic story and turned it into an epic adventure in which Fiver, Hazel, Bigwig and other rabbits go in search of a new warren after their own has been destroyed to make way for a new housing estate. In the course of their search they encounter much violence and the terrible dictator, General Woundwort.

Adams followed Rudyard Kipling’s precept for anthropomorphic fiction: “You attribute to your animals motives and incentives and ideals that real animals wouldn’t have. On the other hand they are very animal to this extent: they never do anything of which real animals would be physically incapable.” For scientific background he used R M Lockley’s The Private Life of the Rabbit.

When the novel was completed Adams sent it off to agents and publishers. It was rejected seven times before a small publisher, Rex Collings, took it. According to Adams, Collings got review copies “on to every desk that mattered”. The first edition came out in 1972, then in 1973 Penguin issued it as a Puffin children’s book.

Critics raved: the book was ranked alongside Animal Farm, C S Lewis, JRR Tolkien, Kenneth Grahame and even Jonathan Swift. In March 1973 it received the Guardian’s children’s fiction award. A year later Macmillan published it in America as an adult title, and two weeks later it was number one on the New York Times bestseller list, remaining there for 33 weeks and selling some 700,000 copies in hardback. The US paperback rights were sold for $800,000 (£655,000).

The paperback edition was published in 1975, by which time Adams had published his second novel, Shardik, in the UK and retired from the civil service to concentrate on writing. Adams regarded Shardik (1974), as his best book. It was certainly an impressive imaginative achievement: he invented an ancient empire in Asia Minor, and the title character is a huge bear alternately worshipped and persecuted by its savage inhabitants. He wanted it to be “a Rider Haggard story” and saw it as an “attempt to write a major, large-scale tragic novel for children”. Critics generally admired his invention and narrative skill but found the many human characters unconvincing.

Late in 1974 Adams went to the University of Florida as visiting professor of poetry for a year, then on to Virginia to be writer in residence at Hollins College. He wrote the prose for a couple of non-fiction works about nature; inspired by a picture by Nicola Bayley, he created the story The Tyger Voyage about two tigers living in Victorian England; and he composed the verse for The Ship’s Cat, the story of a feline pirate on the Spanish Main illustrated by Alan Aldridge and Harry Willock.

But mostly he was working on his third novel, The Plague Dogs, an adventure story about two dogs helped by a fox after they have escaped from an animal experimentation laboratory. He set it in the Lake District, where he and his wife had honeymooned 25 years before. He intended it as a satire on animal experimentation, government and the tabloid press. When it was published in 1977 he was praised, as usual, for his descriptive writing about the natural world and for creating believable animals but his satire was seen as heavy-handed and his human characters two-dimensional.

A year later the animated film of Watership Down came out. It was criticised in some quarters because there seemed to be too much red ink splashed about for a children’s film. Adams was disappointed for other reasons. “It alters the book much too much. They came before making the movie to draw pictures of the landscape but the film wasn’t like the real thing.”

None of his many books thereafter – they included The Iron Wolf (1980), The Bureaucrats (1985), The Legend of Te Tuna (1986) and Traveller (1988) – achieved the massive success of his first three. His writing method remained the same: he wrote in longhand on legal pads, revising constantly and producing a maximum of 1,000 words a day. Each day he prepared by reading aloud from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene or Marcel Proust in translation.

His main attempt at a contemporary novel, a love story called The Girl In A Swing, was published in 1980 to lukewarm reviews. However, being a rather conservative figure and a devout Anglican, he wasn’t a fan of the contemporary novel. He once said: “It would be quite beyond me to write a true novel – a story of contemporary people in a contemporary setting, by implication examining contemporary morality … I need the anthropomorphic distance of using animals.”

For a time he and Barbara lived on the Isle of Wight but eventually moved to Whitchurch in Berkshire near to where both of them had been born and had grown up; the real Watership Down was about six miles from their house.

Later, he published his autobiography, The Day Gone By, in 1990. In it he referred to the fact that he could quite lose himself in an enthusiasm of the moment. On a publicity tour of the United States, he was booked to appear on The Johnny Carson Show but failed to turn up because he was engrossed in conversation with Groucho Marx, whose films he greatly admired, and forgot the time.

For his last published work, Tales from Watership Down (1996), he returned to the rabbit world he had created. He was insistent, however, that it was not a world intended only for children. “Watership Down is not a children’s book,” he said. “I’m very firm about it. It was told to the children to introduce them to a novel. It wasn’t meant to be marketed as a children’s book. They tried to do that. I’m sometimes asked by people for what age group the book was written. I say from eight to 88.”

Richard George Adams, writer: born Newbury, Berkshire 9 May 1920; died 27 December 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks