Altruism has more of an evolutionary advantage than selfishness, mathematicians say

Scientists say they have proved that doing good things for no personal gain can have an evolutionary advantage in the long run

Altruism is real and developed because it confers an evolutionary advantage that is ultimately greater than the benefits of selfishness, an international team of mathematicians claims to have proved.

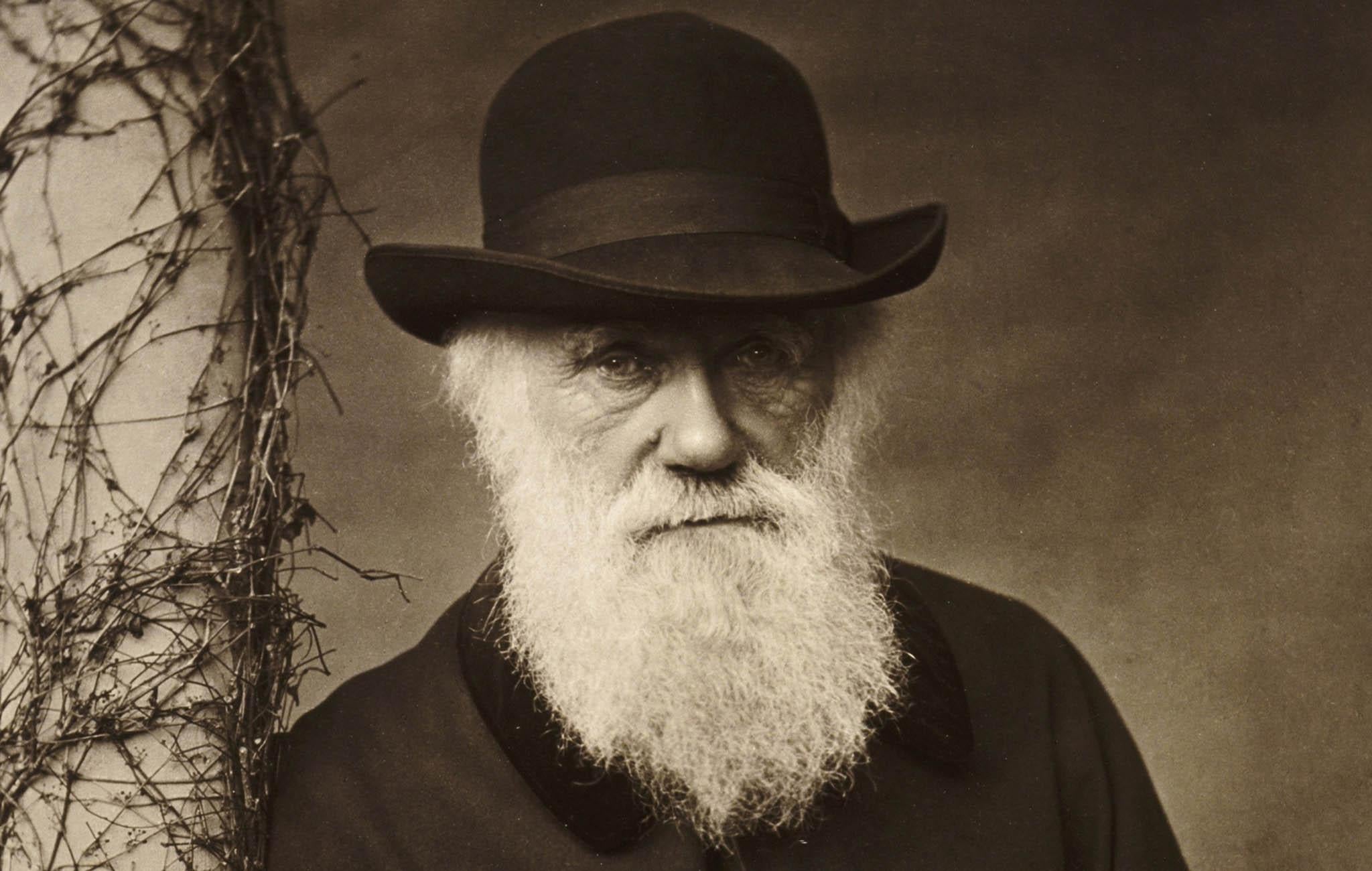

Evolutionary biologists have sometimes struggled with the idea that genuine altruism can exist, given the belief that all life is shaped by a constant Darwinian battle that allows only the “survival of the fittest”.

Amid such a bitter contest, why would one organism help another without getting something in return?

But the mathematicians, led by Dr George Constable, of Princeton University in the US, now believe they have come up with a proof that explains why putting yourself out for someone else can be better in the long-run.

The process is so basic that it can be seen in the yeast fungus. It is capable of producing an enzyme that breaks down complex sugars in the environment, creating more food for all.

But this means expending energy that could otherwise be used for reproduction, so a mutant strain of ‘cheaters’ that selfishly avoid contributing to food production would appear to have a distinct advantage.

However too many cheaters and the food will start to run out, causing the population to crash. A higher proportion of ‘altruistic’ yeast means there will be more food and a higher population.

So groups with higher numbers of ‘altruists’ are better able to survive the random catastrophic events that happen from time to time.

Dr Tim Rogers, a co-author of a paper about the new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, said: “If you have two groups of people, one of whom was very altruistic and another group that was more selfish, it’s the altruistic, more social guys, who are better able to survive the bad winter or the drought.”

He admitted that evolutionary theory suggested there would always be an “innate tendency to become more selfish”.

“If everybody else is doing the right thing, maybe it’s not so bad if you just 'sneak a few,'” said Dr Rogers, of Bath University.

“But if it’s always better to cheat, why doesn’t everybody cheat? The answer is it brings you bad luck, in a sense.”

Dr Rogers said they had shown mathematically that “altruistic behaviour is favoured by chance when the benefits of cheating are sufficiently small compared to a, how well the population would do without any cheats, and b, the typical size of random fluctuations in the population”.

The paper could have significant real-world implications.

“Our research suggests if society goes down a more selfish route, then it’s going to be less able to do well and survive the harsh realities of the world we live in,” Dr Rogers said.

“Take the behaviour of the banks leading up to the [2008 financial] crisis … people were able to cash in on bad decisions before the big event that triggered the crash in the system.”

The bankers were partly influenced by the desire to get annual bonuses. “That short-term thinking means they are not exposed yet to the random fluctuations that would drive the increase in altruism,” Dr Rogers said.

He pointed to a suggestion that it might be better if bankers’ bonuses were delayed by a number of years and said this could “help even out that sense of taking really short-term, instantaneous gains” and promote more responsible behaviour.

The acclaimed evolutionary biologist Professor John Haldane, who died in 1964, was among those who tried to explain altruistic behaviour in terms of the 'self-interest' of genes shared with relatives to different degrees.

Once asked if he would give his life to save his brother from drowning, he gave an answer that seems to bear little relation to reality: “No, but I would to save two brothers or eight cousins.”

But Dr Rogers said: “He’s assuming that you know these drowning people, who they are and how well related to them you are and of course you don’t [necessarily] know that.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks