Ancient Babylonians used early calculus to track path of Jupiter, study finds

Technique that became basis of modern-day graphs did not emerge in medieval Europe until 1400 years later

The ancient Babylonians used a complex form of geometry to compute the movements of Jupiter about 1400 years earlier than the invention of the same technique in medieval Europe – a technique that became the basis of modern-day graphs, a study has found.

An historian of science has discovered evidence that Babylonian priests living between 350BC and 50BC invented and used an abstract form of geometry that until now was thought to have been invented in the 14th Century, eventually evolving into calculus, the mathematical study of how something changes over time.

Although algebra and geometry were both well known in ancient Babylonia – a culture extending back to 1800BC – as well as in the later period of ancient Greece, this is the first time that anyone has found evidence to show that Babylonian scholars knew how to use geometry to plot the irregular movements of a planet, said Mathieu Ossendrijer, professor of the history of ancient science at Humboldt University in Berlin.

“What is new is that the Babylonians also used geometry in their astronomy. We have evidence that they used geometrical figures to gauge the motion of planets but the really exciting thing is that the kind of geometry they used is very special,” Professor Ossendrijver said.

“What we have found essentially is almost like a modern-day graph – a geometrical figure that represents an abstract mathematical space. That’s really new and exciting as it was thought to have been first invented much later, around 1350,” he said.

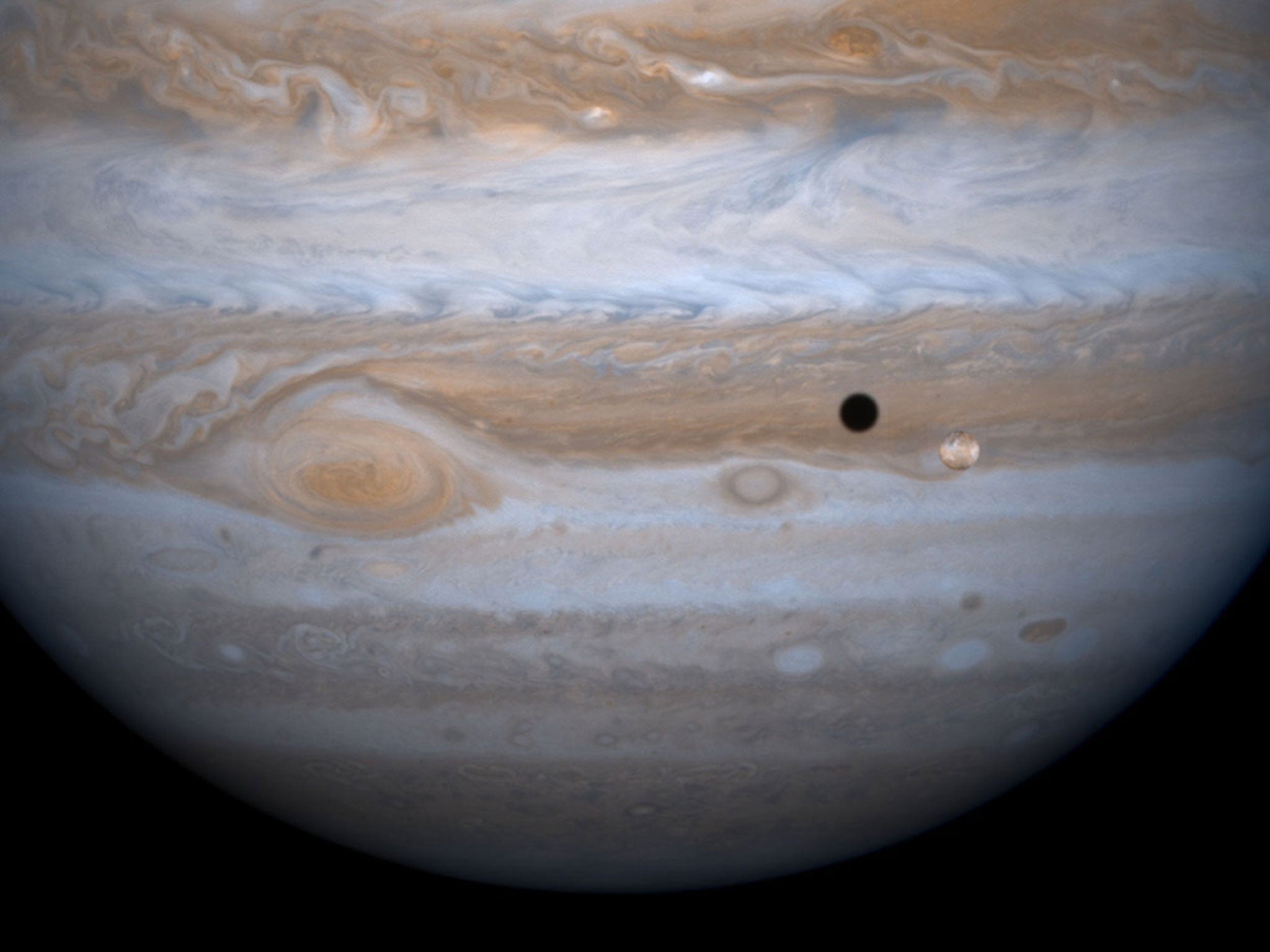

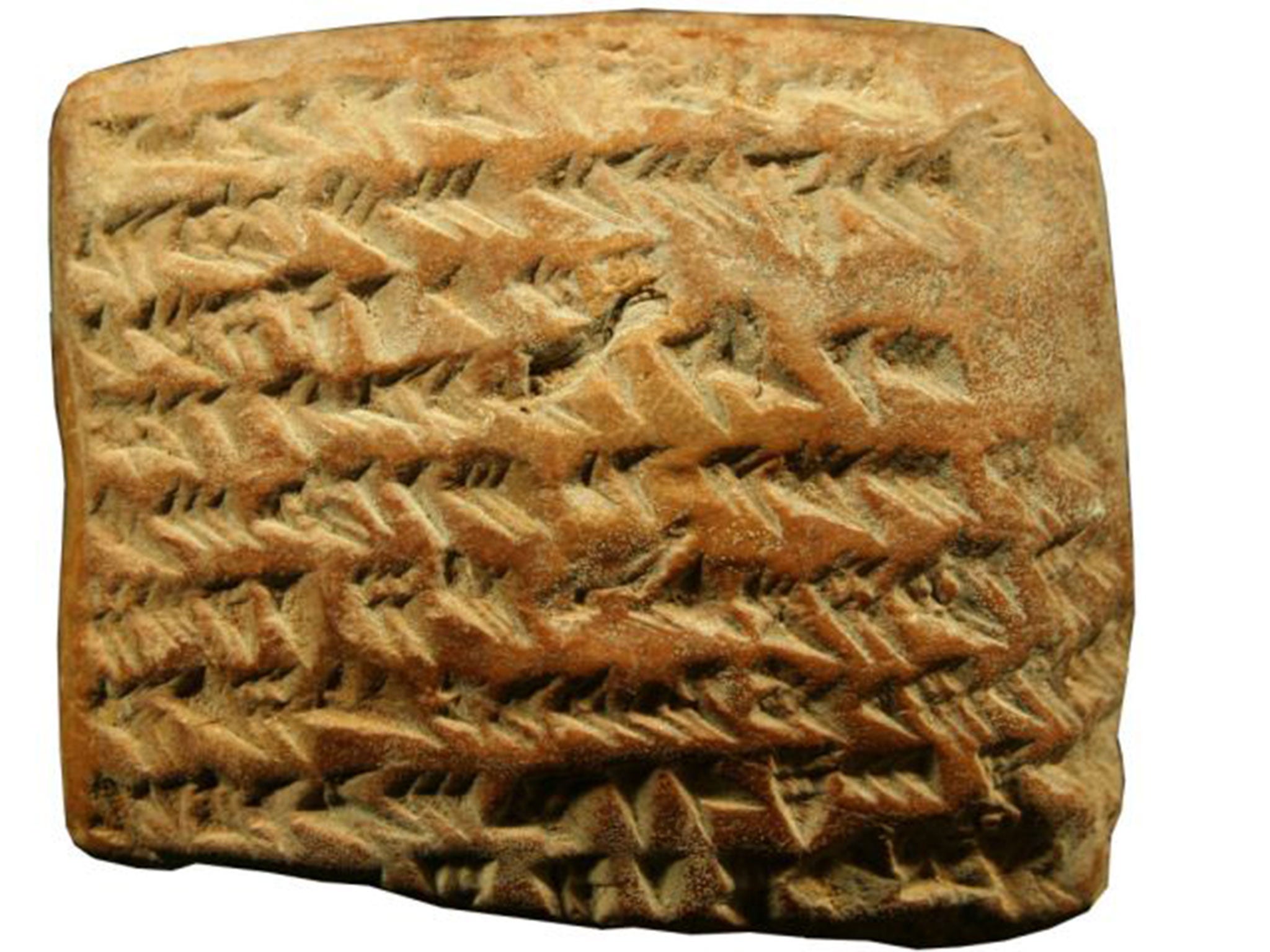

Babylonian cuneiform text etched onto clay tablets held in the British Museum in London has revealed that the priests were calculating the movements of Jupiter during the first 60 days it appeared above the horizon by plotting the planet’s irregular motion away from the regular path of the Sun.

Jupiter’s movement across the sky appears to slow, although it is in fact due to the relative movements of its orbit with respect to the Earth’s. A graph of Jupiter’s apparent velocity against time would therefore slope down so that the area under the curve forms a trapezoid – a four-sided shape with a sloping top.

It is clear from the clay tablets that the Babylonians were able to plot Jupiter’s movements as a line on a graph of movement against time, and then calculating the distance moved by measuring the area formed by the four-sided trapezoid shape of the graph – a shape the Babylonian priests called the “oxen head”.

It was this ability to compute the movements of an object moving with a changing velocity using geometric principles that was unheard of before the 14th Century AD, Professor Ossendriver said.

“It’s like a precursor if you like of what we know today as integral calculus, which allows us to calculate the movements of decelerating or accelerating objects. It’s a concept that was invented twice; once in ancient Babylonia and then re-invented around 1350 in medieval Europe. The ancient Greeks never did this,” he said.

There are no geometrical shapes or graphs depicted on the clay tablets, and all the descriptions are in cuneiform script. However, it is clear from the well-documented terminology used by the priests that they were referring to this form of abstract geometrical calculation, Professor Ossendrijver said.

“The tablets were written by priests in the temple. They computed the position of all five planets that they knew about, but Jupiter had the largest number of texts devoted to it. This was probably because Jupiter was associated with the supreme god of Babylon, Marduk,” Professor Ossendrijver said.

The study is published in the journal Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks