One of Scotland's first migrants had dark hair, brown eyes and was lactose-intolerant, skeleton DNA test reveals

‘Caithness is considered one of the most peripheral parts of Europe, but in fact, people have been moving there for thousands and thousands of years’

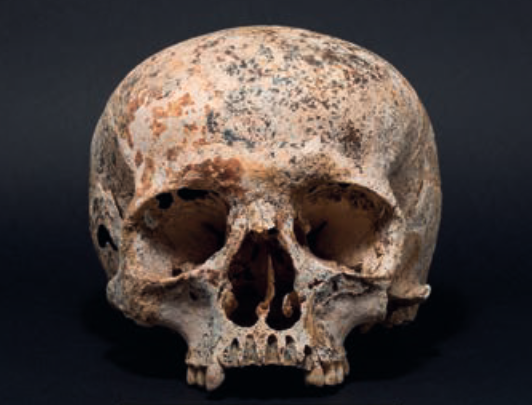

A skeleton at least 4,250 years old found in the north of Scotland in 1987 has surprised archaeologists after new analysis has revealed she was a migrant from northern Europe.

When the skeleton was first found, the remains were discovered alongside a beaker, flint artefacts and cow bones.

Early work revealed the skeleton – who has become known as Ava – belonged to a woman aged between 18–25 who had been buried in an unusual grave cut into bedrock at Achavanich in Caithness.

A previous reconstruction of her appearance gave her blue eyes and red hair, but fresh DNA analysis has revealed she was more likely to have brown eyes and black hair, and was probably had a darker complexion than the local Neolithic population.

The genetic information also indicates Ava would have had an intolerance to lactose.

“When we started to explore the ancestry aspect of her DNA, we realised that genetically she had no relation to the local population who were residing in Caithness before her,” the study’s lead author, Maya Hoole, told The Independent.

“Her ancestors look like they moved into the Caithness area a few generations before she was born, suggesting she was a first or second generation migrant, with her predecessors most likely coming from somewhere in Northern Europe, such as the Netherlands.”

The original find was made by archaeologist Robert Gourlay after the skeleton and the beaker – a clay pot – were found by two men quarrying rock for a nearby road – the A9 between Thurso and Latheron.

The DNA analysis was undertaken by a team working at London’s Natural History Museum and Harvard Medical School in the US. The scientists have produced a new facial reconstruction of what Ava may have looked like.

“I get goosebumps every time I look at the facial reconstruction,” Ms Hoole said. “It is a little bit like time-travel. We now know so much about this young woman, we can recreate aspects of her life – and death – in remarkable detail.

“For me, that is extremely rewarding because it is what I hoped to achieve when I first set out – but I never thought we would be able to find out so much.”

Speaking about the irony of the skeleton being found with a cow scapula when Ava was lactose intolerant, Ms Hoole said: “Today we primarily associate cattle with dairy farming, but in this prehistoric society they were perhaps more of a meat resource than a dairy resource. Having said that, she would have been able to consume some processed dairy products such as fermented milk, yoghurt or some cheeses. It looks like the majority of her population were in fact lactose intolerant.”

The burial style is unusual. Bronze-age skeletons are more commonly found buried beneath cairns on in graves dug into soil.

The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, suggest Ava was buried soon after her death and that the presence of the cow scapula was as a food offering – a shoulder of beef.

Ms Hoole said she came across the archive for the excavation when she was a graduate trainee working for the Highland Historic Environment Record in 2014 and has been working on the project independently and unpaid in her free time ever since.

“It instantly interested me, and I couldn’t believe that no-one else had undertaken any further studies on this site since it was uncovered in the late 1980s.”

Ava was named after the research team abbreviated the place name Achavanich to Ava for the title of the project, but it began to be used interchangeably for the individual.

The study’s co-author, Tom Booth, of the Natural History museum said: “Our previous work looking at ancient DNA from hundreds of prehistoric British skeletons had already established that there was an influential movement of people from mainland Europe around 2500 BC which transformed the local population and their cultures. However, the reconstruction of Ava brings a sense of humanity to a story which can often appear as an abstract mass of bones, genes and artefacts.

“Her ancestors arrived in the area only a few generations before she lived, yet the evidence suggests she was profoundly connected to the area in which she was found. She grew up there and when she died, her body was buried in a grave cut into the local bedrock.

“That she perhaps looks slightly different from what people would expect from someone living in northern Scotland adds an extra level of intrigue and is testament to the difficulties in projecting modern assumptions onto the past, particularly prehistory, which is inherently strange.”

Ms Hoole added: “What we’ve discovered highlights again how much movement there has been between the UK and mainland Europe throughout time. Caithness is often considered to be one of the most peripheral parts of Europe, but in fact, people have been moving there for thousands and thousands of years.

“Scotland does have its own story to tell, but it is also a part of a much larger, wider narrative that has been written over many a millennia.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks