World’s second-largest egg found in Antarctica may belong to giant sea lizard

Unrecognised specimen was known as 'The Thing' for almost a decade until one expert suggested it may be soft-shell egg

Scientists in the US believe they are closer to solving the mystery of what a peculiar large fossil found in the Antarctic in 2011 could be, saying it is likely to be an enormous soft-shell egg laid by an extinct giant sea lizard.

After the fossil was found by Chilean scientists, the specimen was apparently left unlabelled and unstudied in the collections of Chile’s National Museum of Natural History, with those who knew about its existence only referring to it by its nickname – “The Thing”.

However, the object, which looks something like a deflated football sculpted in rock, has recently undergone analysis by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, who found it is a 66 million-year-old soft-shell egg, and at more than 11x7 inches (28x18cm), it is the second-largest egg of any known animal.

The specimen is the first fossil egg ever found in Antarctica and the discovery pushes the limits of how big scientists thought soft-shell eggs could grow, the research team said.

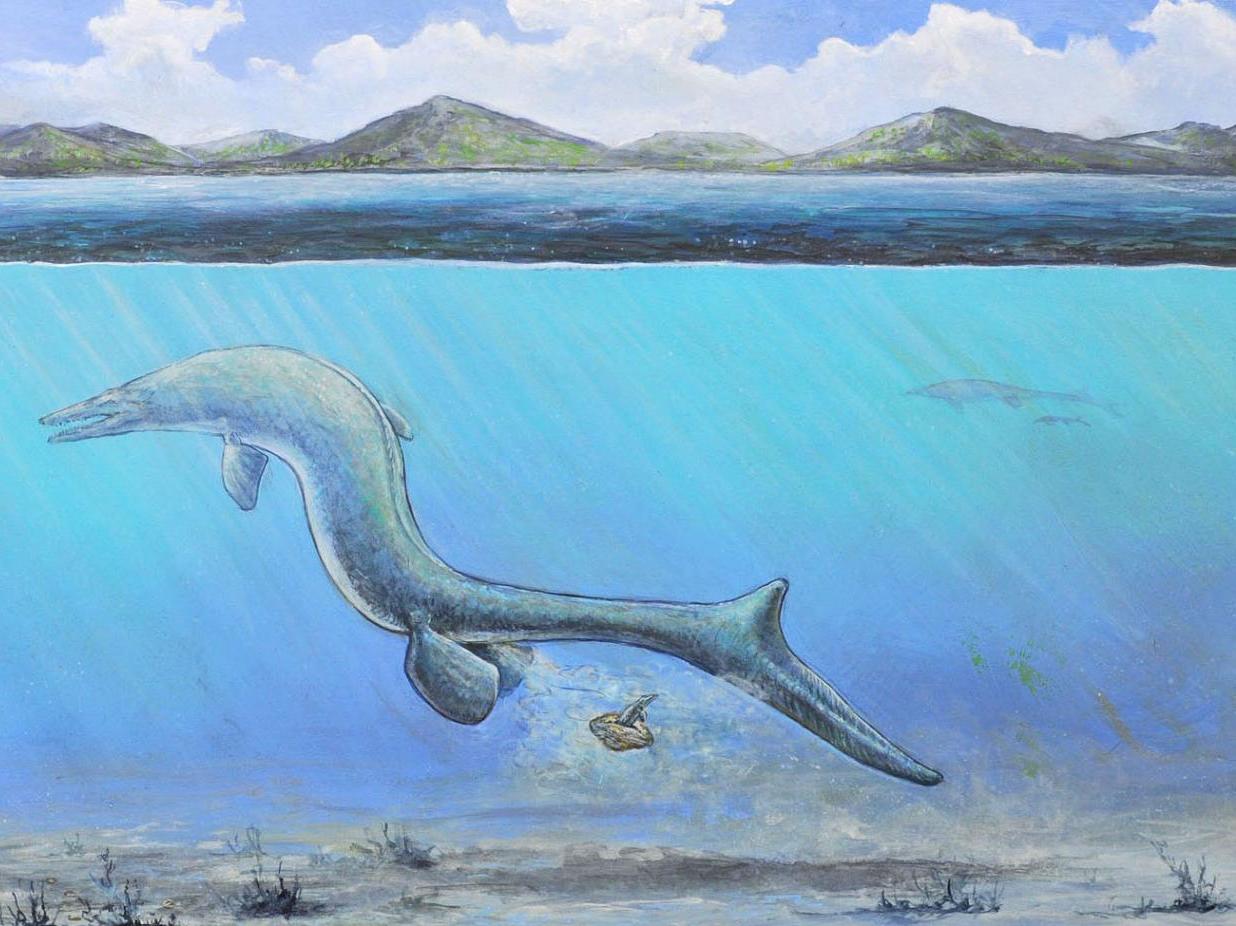

In addition to its astounding size, the fossil is significant because scientists think it was laid by an extinct, giant marine reptile, such as a mosasaur – a discovery that challenges the prevailing thought that such creatures did not lay eggs.

“It is from an animal the size of a large dinosaur, but it is completely unlike a dinosaur egg,” said lead author Lucas Legendre, a postdoctoral researcher at UT Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences.

“It is most similar to the eggs of lizards and snakes, but it is from a truly giant relative of these animals.”

Co-author David Rubilar-Rogers of Chile’s National Museum of Natural History was one of the scientists who discovered the fossil in 2011. He showed it to every geologist who came to the museum, hoping somebody had an idea, but he didn’t find anyone until Julia Clarke, a professor in the Jackson School’s Department of Geological Sciences, visited in 2018.

“I showed it to her and, after a few minutes, Julia told me it could be a deflated egg!” Dr Rubilar-Rogers said.

Upon microscopic study of the specimen Dr Legendre found several layers of membrane, indicating the fossil was indeed that of an egg.

The structure is very similar to transparent, quick-hatching eggs laid by some snakes and lizards today, he said. However, because the fossil egg is hatched and contains no skeleton, Dr Legendre had to use other means to pinpoint the type of reptile which had laid it.

He compiled a dataset to compare the body size of 259 living reptiles to the size of their eggs, and the data indicated the reptile that laid the egg would likely have been more than 20 feet long from the tip of its snout to the end of its body, not including a tail. In both size and living reptile relations, an ancient marine reptile fits the bill.

Furthermore, the rock formation where the egg was discovered also hosts skeletons from baby mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, along with adult specimens.

“Many authors have hypothesised that this was sort of a nursery site with shallow protected water, a cove environment where the young ones would have had a quiet setting to grow up,” Dr Legendre said.

The paper does not discuss how the ancient reptile might have laid the eggs. But the researchers have two competing ideas.

One involves the egg hatching in the open water, which is how some species of sea snakes give birth. The other involves the reptile depositing the eggs on a beach and hatchlings scuttling into the ocean like baby sea turtles. The researchers said this approach would depend on some “fancy manoeuvering” by the mother because giant marine reptiles were too heavy to support their body weight on land. Laying the eggs would require the reptile to wriggle its tail on shore while staying mostly submerged, and supported, by water.

“We can’t exclude the idea that they shoved their tail end up on shore because nothing like this has ever been discovered,” Professor Clarke said.

The largest known eggs ever to have existed come from the extinct Madagascan elephant bird. The animal’s eggs measured 13 in (33 cm) long and had a liquid capacity of 8.5 litres – roughly equivalent to seven ostrich eggs, according to Guinness World Records.

The elephant bird became extinct about 1,000 years ago – probably due to humans hunting them.

The study describing the fossil egg is published in the journal Nature.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks