Scientists measure largest ever collision of two black holes

Scientists say the two black holes merged after colliding at speeds near the limit allowed by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity

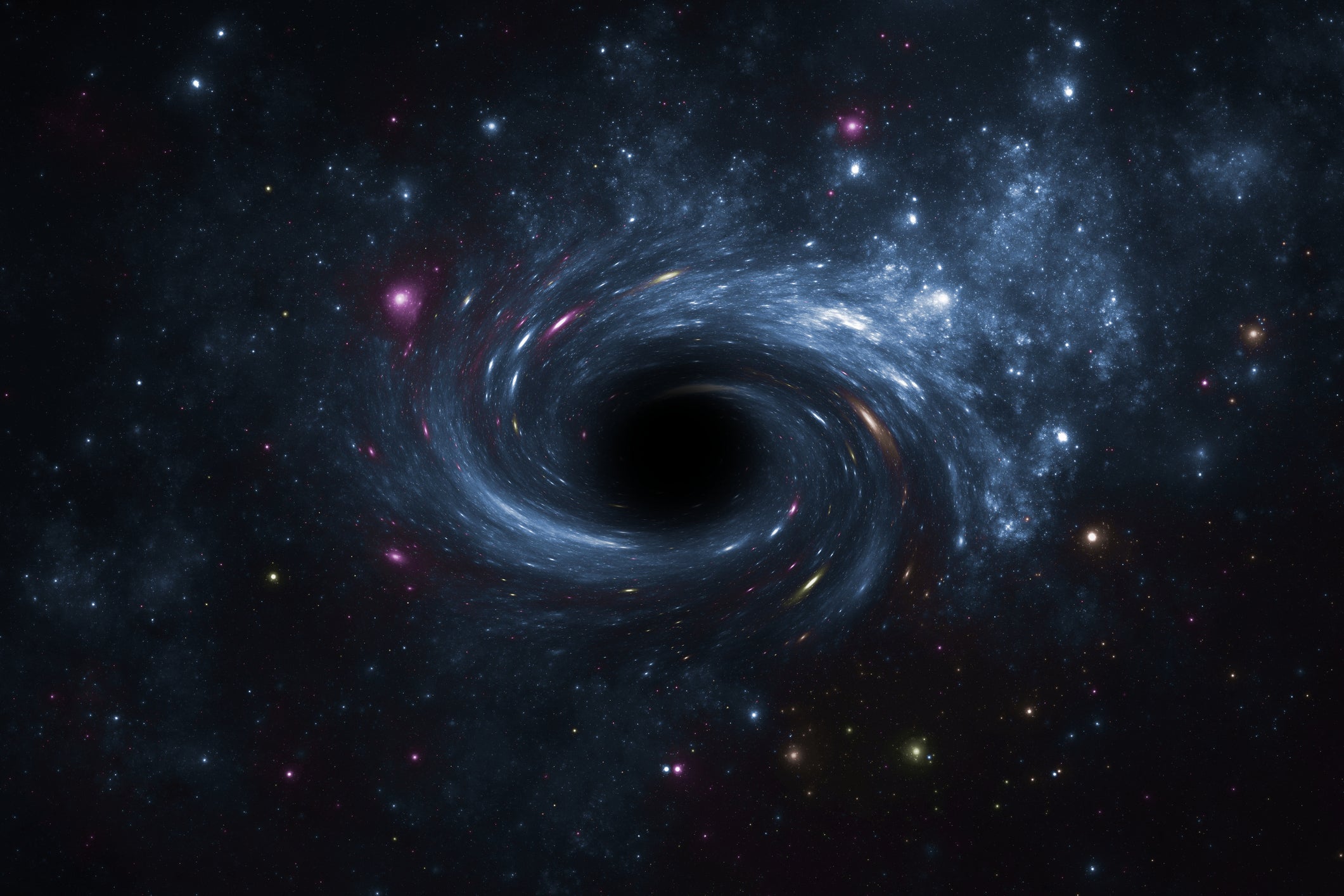

Two black holes have collided far beyond the distant edge of the Milky Way, creating the biggest merger ever recorded by gravitational wave detectors.

The two phenomena, each more than 100 times the mass of the sun, had been circling each other before they violently collided about 10 billion light years from Earth.

Scientists at the Ligo Hanford and Livingston Observatories detected ripples in space-time from the collision just before 2pm UK time on 23 November 2023, when the two US-based detectors in Washington and Louisiana twitched at the same time.

Alongside their enormous masses, the signal, dubbed GW231123 after its discovery date, also showed the black holes spinning rapidly, according to researchers.

“This is the most massive black hole binary we’ve observed through gravitational waves, and it presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation,” said Professor Mark Hannam, from Cardiff University and a member of the Ligo Scientific Collaboration.

Gravitational-wave observatories have recorded around 300 black hole mergers.

Prior to GW231123, the heaviest merger detected was GW190521, whose combined mass was 140 times that of the sun. The latest merger produced a black hole up to 265 times more massive than the sun.

“The black holes appear to be spinning very rapidly — near the limit allowed by Einstein’s theory of general relativity,” said Dr Charlie Hoy from the University of Portsmouth.

“That makes the signal difficult to model and interpret. It’s an excellent case study for pushing forward the development of our theoretical tools.”

“It will take years for the community to fully unravel this intricate signal pattern and all its implications,” said Dr Gregorio Carullo, assistant professor at the University of Birmingham.

“Despite the most likely explanation remaining a black hole merger, more complex scenarios could be the key to deciphering its unexpected features. Exciting times ahead!"

Facilities like Ligo in the United States, Virgo in Italy, and KAGRA in Japan are engineered to detect the tiniest distortions in spacetime caused by violent cosmic events such as black hole mergers.

The fourth observing run began in May 2023, and data through January 2024 are scheduled for release later this summer.

“This event pushes our instrumentation and data-analysis capabilities to the edge of what’s currently possible,” says Dr Sophie Bini, a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech.

“It’s a powerful example of how much we can learn from gravitational-wave astronomy — and how much more there is to uncover.”

GW231123 is set to be presented at the 24th International Conference on General Relativity and Gravitation (GR24) and the 16th Edoardo Amaldi Conference on Gravitational Waves, held jointly as the GR-Amaldi meeting in Glasgow, from 14 to 18 July.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks