Cannibals who once lived in Somerset cave engraved human bones as part of eating ritual, study finds

'The engraving of this bone may have been a sort of ‘story-tale’ more directly related to the deceased than the surrounding landscape'

Human bones appear to have been engraved as part of a “complex” cannabalistic ritual by people who once lived in Somerset, according to new research.

The bones, which had a number of deliberate cuts and human tooth marks, were discovered at Gough’s Cave in the Mendip Hills and are believed to be between 12,000 to 17,000 years old.

The cave has been associated with cannibalism before but the marks provide evidence that eating human flesh was a ritualistic behaviour.

Despite numerous accounts of people living as cannibals throughout history, the practice is believed to be almost entirely associated with religious behaviour or funerary rituals with no conclusive evidence that any group of people relied on human flesh as a staple food.

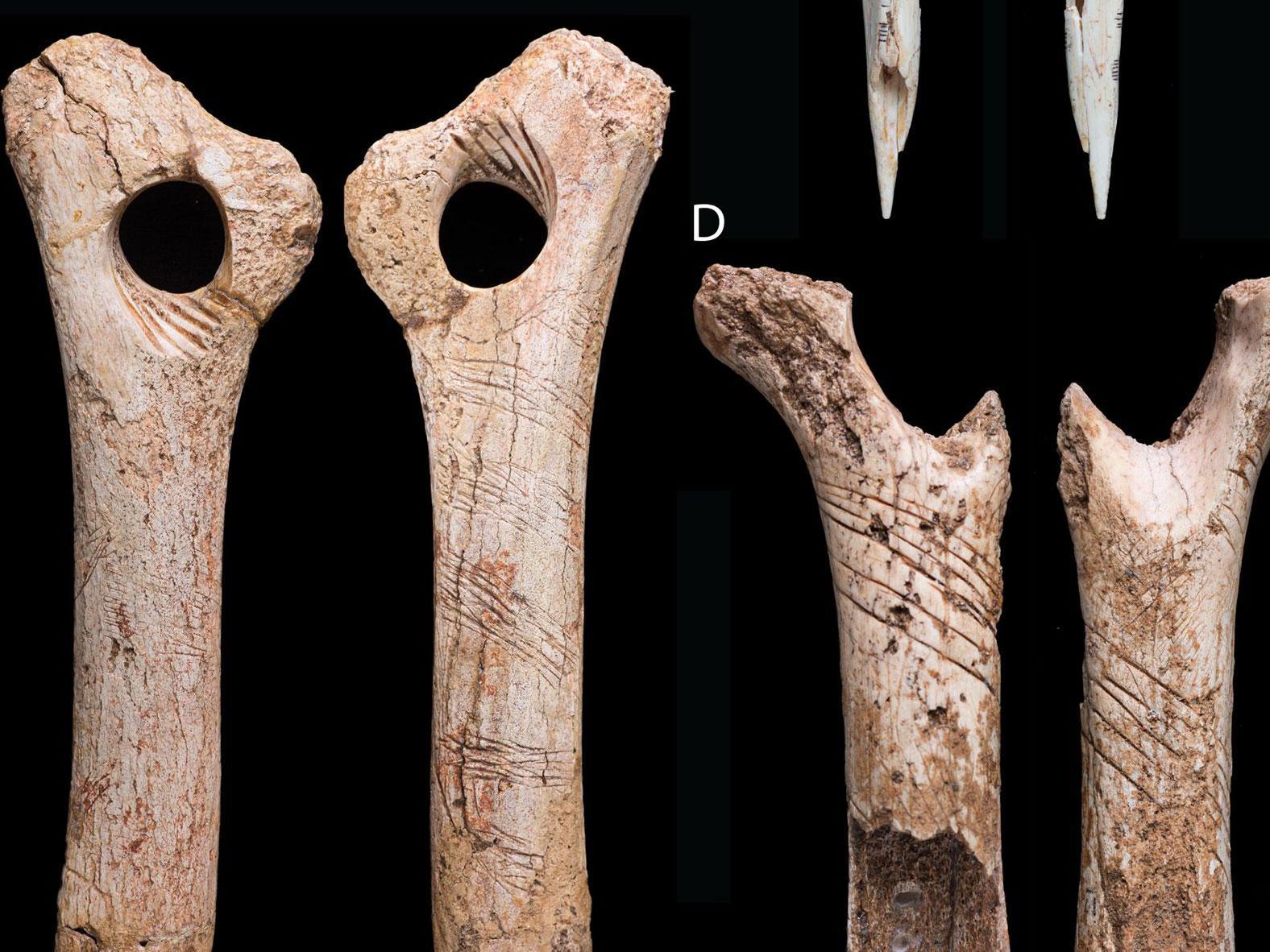

There has been a debate about whether the marks on the bones found at Gough’s Cave were simply caused by the process of butchering the corpses or whether they had been internationally engraved.

But, writing in the journal Plos One, researchers from the Natural History Museum concluded there was “no doubt” that a series of “zig-zagging incisions … are engraving marks, produced with no utilitarian purpose apart from an artistic representation”.

“Similar to other engraved bone artefacts from Gough’s Cave, the incisions are very consistent in their lengths, overall pattern, and technique of production,” they added.

“Unlike filleting marks, which are generally produced in a single-stroke slicing motion, the engraving is produced by a combination of single-stroke, to-and-fro, and scraping incisions.”

The researchers said that the engravings appeared to have been made by a single individual using one tool at one time.

And, after the carvings were made, the bones were broken to extract their marrow.

“The sequence of the manipulations strongly suggests that the engraving was an intrinsic part of the multi-stage cannibalistic ritual and, as such, the marks must have held a symbolic connotation,” the researchers wrote.

“We can only speculate about the context in which this happened. The engraving of objects and utilitarian tools has been linked to ways of remembering events, places or circumstances, a sort of ‘written memory’ and ‘symbolic glue’ that held together complex social groups.

“The engraving of this bone may have been a sort of ‘story-tale’ more directly related to the deceased than the surrounding landscape, perhaps indicative of the individual, events from their life, the way they died, or the cannibalistic ritual itself.”

They said the bones were not made to be carried around, but were “quickly engraved, with minimal preparation … then broken and discarded”.

This suggested it was part of a “complex funerary cannibalistic behaviour that has never been recognised before for the Palaeolithic period”.

Dr Silvia Bello, a Natural History Museum researcher, said the engraving of the bones would have been “rich in symbolic connotations”.

“Although in previous analyses we have been able to suggest that cannibalism at Gough’s Cave was practised as a symbolic ritual, this study provides the strongest evidence for this yet,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments