Largest ever dark matter map suggests Einstein theory may have been wrong

Results of Dark Energy Survey show universe may actually be smoother and more spread out than previously thought

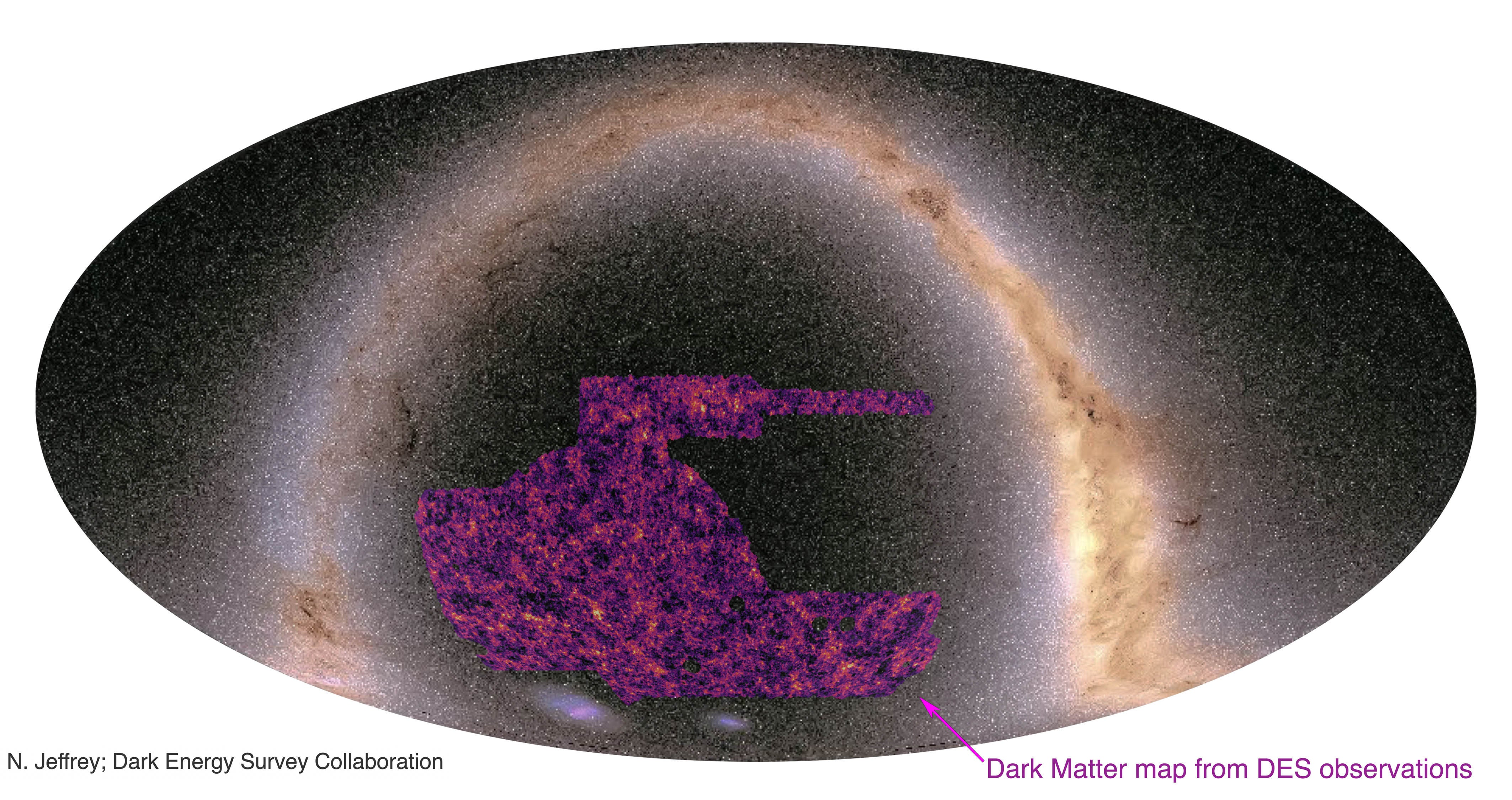

Researchers have created the largest ever map of dark matter – and it could suggest Einstein’s theory of relativity was wrong.

Dark matter is an invisible material thought to account for 80 per cent of the total matter of the universe.

As matter curves space-time, astronomers are able to map its existence by looking at light travelling to Earth from distant galaxies.

If the light has been distorted, this means there is matter in the foreground, bending the light as it comes towards us.

A team co-led by University College of London (UCL) researchers, as part of the international Dark Energy Survey (DES), used artificial intelligence to analyse images of 100 million galaxies, looking at their shape, spots of light made up of 10 or so pixels, to see if they had been stretched.

The new map, a representation of all matter detected in the foreground of the observed galaxies, covers a quarter of the southern hemisphere's sky.

New analysis of the first three years of the DES survey suggests matter is distributed throughout the universe in a way that is consistent with predictions in the standard cosmological model, the best current model of the universe.

But researchers also found hints, as with previous surveys, the universe may be a few per cent smoother than predicted.

This prediction comes from analysis of the light left over from the Big Bang.

Co-lead author Dr Niall Jeffrey, UCL physics and astronomy, told the BBC: “If this disparity is true then maybe Einstein was wrong.

“You might think that this is a bad thing, that maybe physics is broken, but to a physicist it is extremely exciting.”

He added: "Most of the matter in the universe is dark matter. It is a real wonder to get a glimpse of these vast, hidden structures across a large portion of the night sky.

“These structures are revealed using the distorted shapes of hundreds of millions of distant galaxies with photographs from the Dark Energy Camera in Chile.

“In our map, which mainly shows dark matter, we see a similar pattern as we do with visible matter only, a web-like structure with dense clumps of matter separated by large empty voids.

"Observing these cosmic-scale structures can help us to answer fundamental questions about the universe."

For decades astronomers have suspected there is more material in the universe than we can see.

Dark matter, like dark energy, remains mysterious, but its existence is inferred from galaxies behaving in unpredicted ways.

For instance, the fact that galaxies stay clustered together, and that galaxies within clusters move faster than expected.

Co-author Professor Ofer Lahav, UCL Physics and Astronomy, chairman of the DES UK consortium, said: "Visible galaxies form in the densest regions of dark matter.

"When we look at the night sky, we see the galaxy's light but not the surrounding dark matter, like looking at the lights of a city at night.

"By calculating how gravity distorts light, a technique known as gravitational lensing, we get the whole picture, both visible and invisible matter.

"This brings us closer to understanding what the universe is made of and how it has evolved.

"It also shows the power of artificial intelligence methods to analyse one of the largest data sets in astronomy."

The map is described in a new paper posted on the DES website and to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The DES collaboration consists of more than 400 scientists from 25 institutions in seven countries.

Additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks