Man who invented the mug shot: The ground-breaking work of Alphonse Bertillon

As a new exhibition investigates the evolution of the forensic sciences, Nick Clark pores over the unparalleled contribution of the visionary 19th-century criminal profiler Alphonse Bertillon

Towards the end of the first chapter of The Hound of the Baskervilles, a prospective client tells Sherlock Holmes he is only the "second- highest expert in Europe" in criminal matters. When the detective demands to know the identity of his better, the response comes: "To the man of precisely scientific mind, the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly."

The name of Alphonse Bertillon may have dwindled beside that of Holmes, but his fingerprints are all over the early years of the forensic sciences at the end of the 19th century, and his influence persists to this day. The Frenchman developed a number of advanced techniques, most notably in standardising criminal photography – he has been dubbed the "father of the mug shot" – and his work will feature in an exhibition, "Forensics: the Anatomy of Crime", opening this week at the Wellcome Collection.

The criminologist's early life gave little clue that he would rise to the top of the field. As a young man, he left the army and eventually found a lowly junior clerical job at the Prefecture of Police in Paris in 1879. But data was in the blood: his father was chief of the Bureau of Statistics and Alphonse's brother would go on to help found the International Statistics Institute.

When Bertillon took up his post, the criminal records at the prefecture were in chaos. Re-offending rates were rising yet there was no concerted approach to improve the identification of recidivist criminals. So the resourceful Bertillon set to work on a formal cataloguing process.

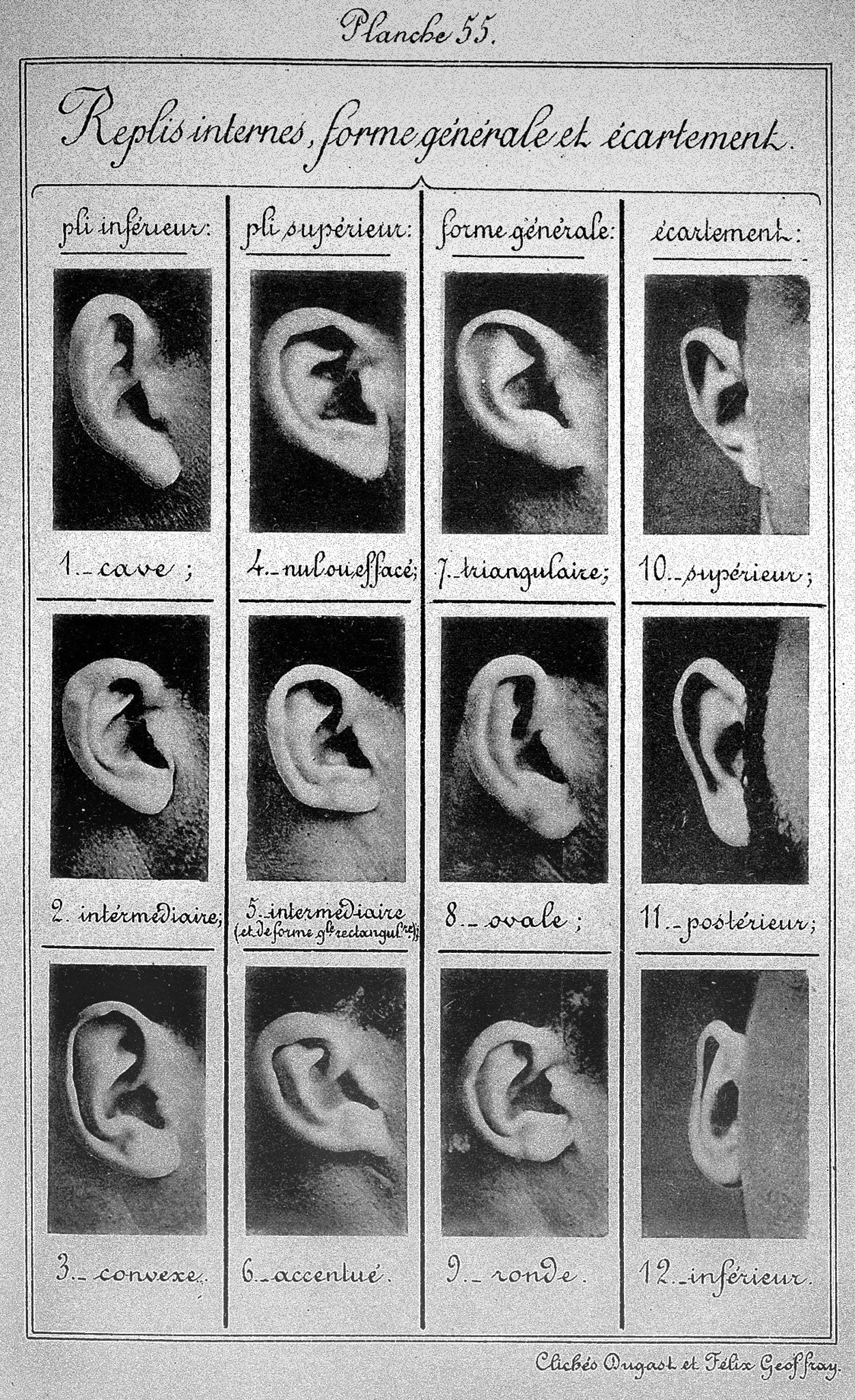

He became interested in anthropometry, the study of human variation, and devised a system of measuring criminals' distinguishing features, developing instruments to measure the length and breadth of the head, arm and finger lengths, foot size – even the protrusion of the eyeball. He then catalogued the measurements of each criminal on individual index cards. The exhibition will display charts Bertillon designed to catalogue physiognomic variations in features that typically arose in identification – nose, chin, hair, eyes.

Anthropometry was based on ideas related to phrenology, the bogus science that claimed k to infer certain character traits from variations in a subject's cranio-facial structure. Yet Bertillon himself was doubtful about phrenology: "I do not feel convinced that it is the lack of symmetry in the visage, or the size of the orbit, or the shape of the jaw, which make a man an evil-doer."

According to the exhibition's curator, Lucy Shanahan, "Bertillon's primary concern was to identify perpetrators as a means of law enforcement by creating a record of unique information about each individual's physical appearance, rather than their criminal tendencies."

Bertillon also worked on practices including forensic document examination, ballistics and the use of materials to preserve footprints. But his lasting legacy came in the field of photography. "He was a pioneer," says Shanahan. "He was taking photos not only of individuals, but crime scenes. He had a whole lab set up for both developing photographs and taking mug shots."

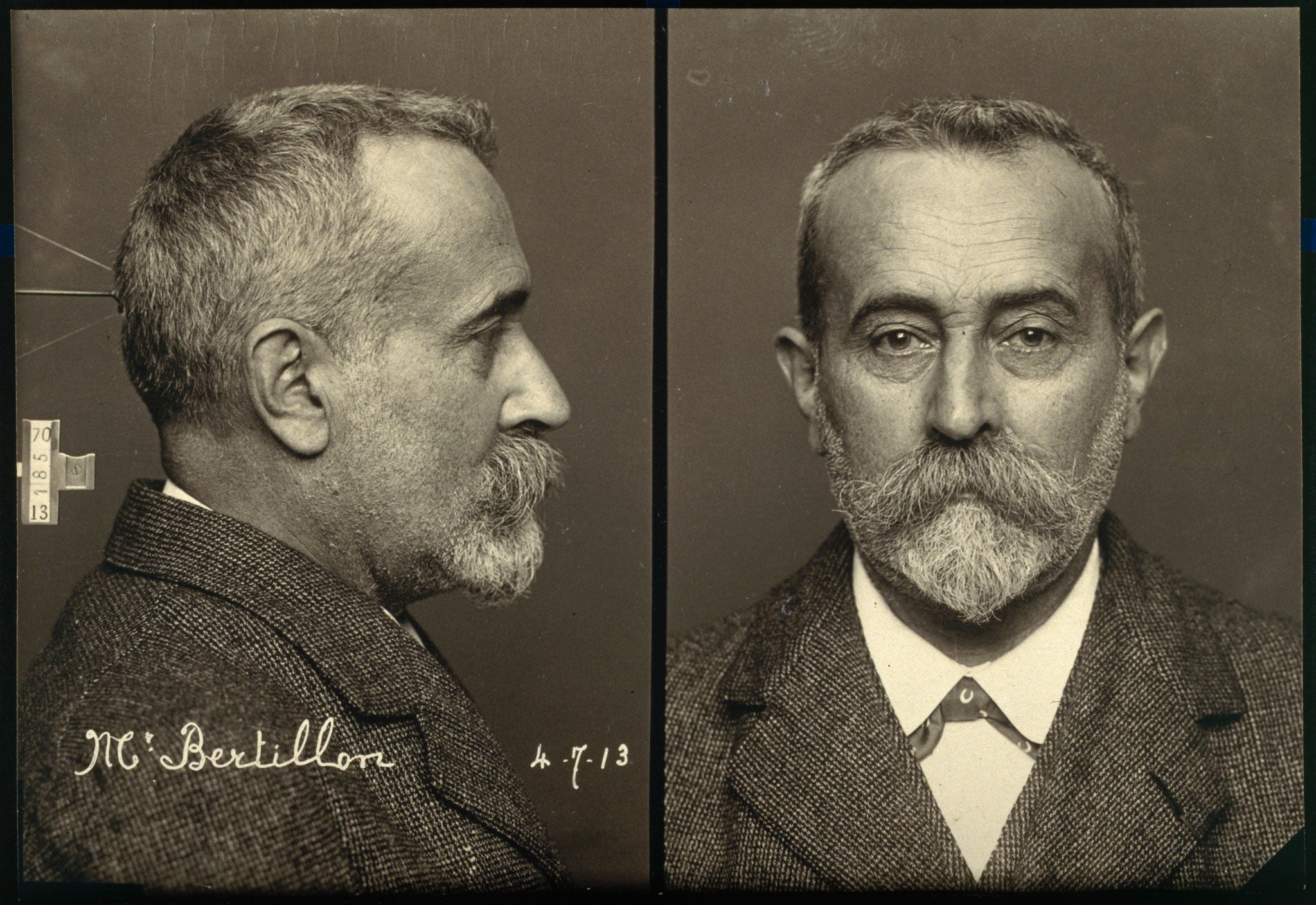

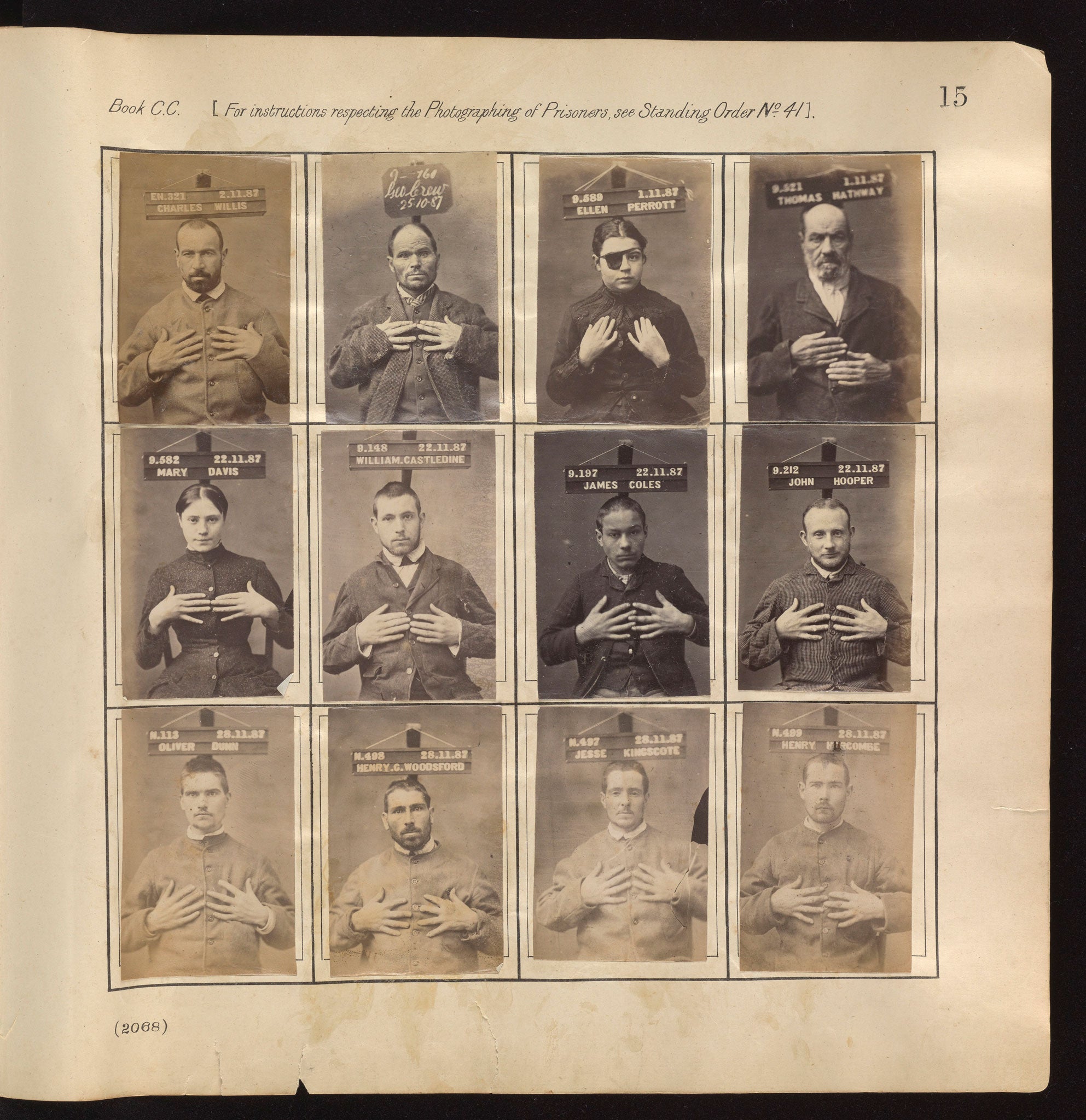

The criminologist brought rigour to crime-scene photography, introducing the "god's eye view" format, taken from above. And, most famously, he standardised the method of taking the criminal's photograph face on and in profile, which would be added to their file card. Police forces had already started to keep "rogues' galleries" soon after the invention of photography in the 1840s, but had previously been "rather disorganised about it", says Shanahan. The exhibition includes a range of early mug shots, including one Bertillon took of himself a year before his death in 1914 at the age of 60.

The breakthrough for his methodology came in 1884, when he identified 241 repeat offenders using their mug shots and measurements. "That was the year when other police forces across Europe started taking notice and implementing his methods and systems," says Shanahan. At the time, the royal commissioner of police in Dresden wrote that Paris was the "Mecca of Police and Bertillon their prophet".

A decade later, the approach that had become known as Bertillonage was formalised in his seminal text Identification Anthropométrique: Instructions Signalétiques. It won him fans in law enforcement and beyond. (In his short story "The Naval Treaty", Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had Sherlock Holmes express "his enthusiastic admiration of the French savant".)

Bertillon's reputation was tarnished partly by his involvement in the Dreyfus affair at the turn of the century; his evidence – later discredited –contributed to the notorious miscarriage of justice. And his complicated anthropometric system would be superseded by fingerprinting in the 1910s. Yet, Shanahan asserts, "he was a visionary": his legacy endures in "many areas of modern-day forensic practice – and the mug shot remains standard practice today".

'Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime' is at The Wellcome Collection, London NW1 (wellcomecollection.org), from Thursday to 21 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks