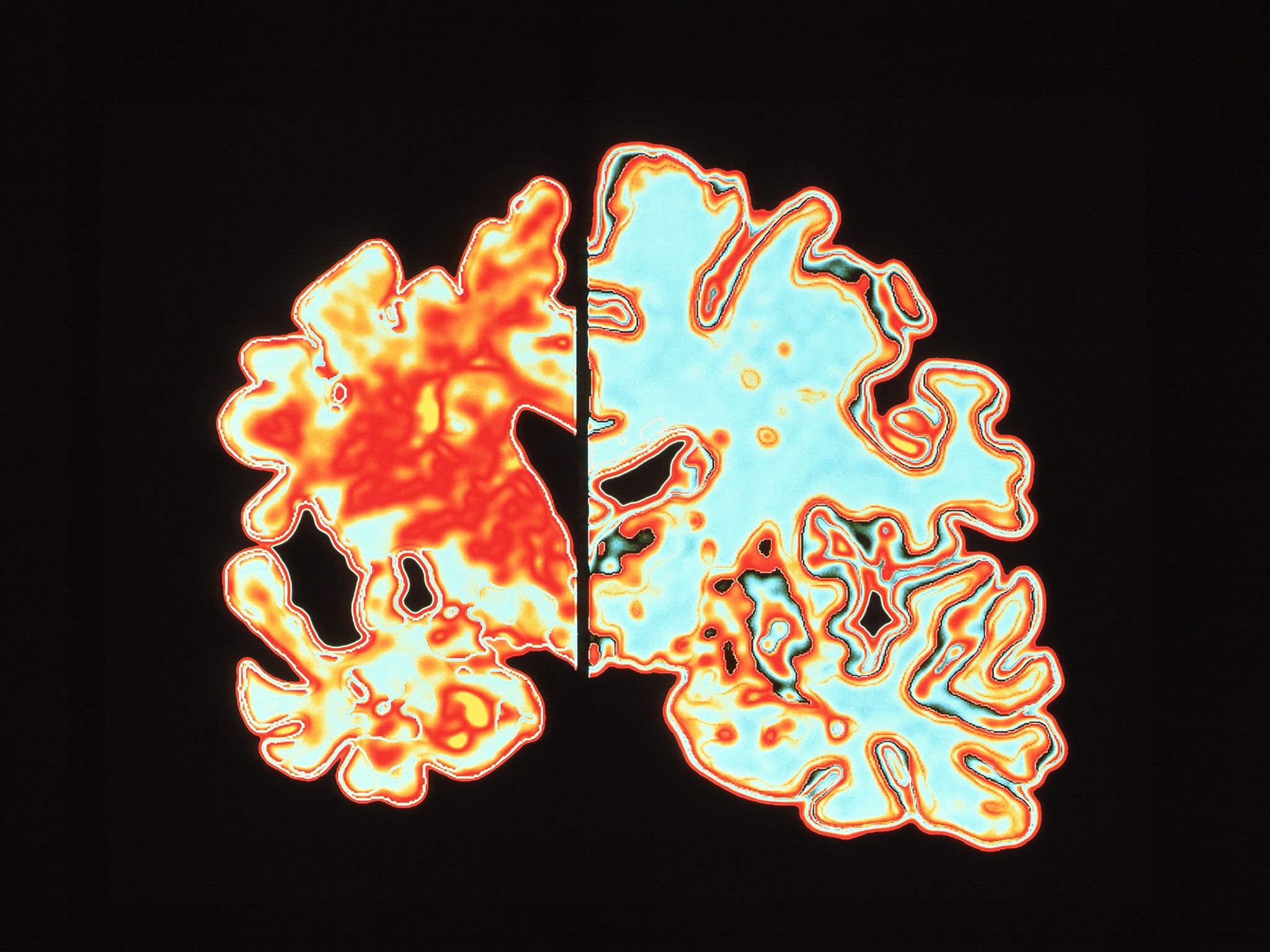

Study could help tackle memory loss associated with conditions such as Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia

Research could also help scientists understand why some unwanted memories are so long-lasting

Our brains can act the same way as email by filing irrelevant thoughts into a neurological trash folder.

Forgetting memories can be the result of an active deletion process rather than a failure to remember, according to new research.

The findings point towards new ways of tackling memory loss associated with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

The study in rats, led by the University of Edinburgh and published in The Journal of Neuroscience, could also help scientists to understand why some unwanted memories are so long-lasting – such as those of people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorders.

Memories are maintained by chemical signalling between brain cells that relies on specialised receptors called AMPA receptors. The more AMPA receptors there are on the surface where brain cells connect, the stronger the memory.

The scientists found that the process of actively wiping memories happens when brain cells remove AMPA receptors from the connections between brain cells. Over time, if the memory is not recalled, the AMPA receptors may fall in number and the memory is gradually erased.

Drugs that target AMPA receptor removal are already being investigated as potential therapies to prevent memory loss. However, researchers said further investigation is needed to understand what consequences blocking this process could have on the ability to take on new information and retrieve existing memories.

Dr Oliver Hardt, of the Centre for Cognitive and Neural Systems at the University of Edinburgh, said: “Our study looks at the biological processes that happen in the brain when we forget something. The next step is to work out why some memories survive whilst others are erased. If we can understand how these memories are protected, it could one-day lead to new therapies that stop or slow pathological memory loss.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks