Vast methane 'plumes' seen in Arctic ocean as sea ice retreats

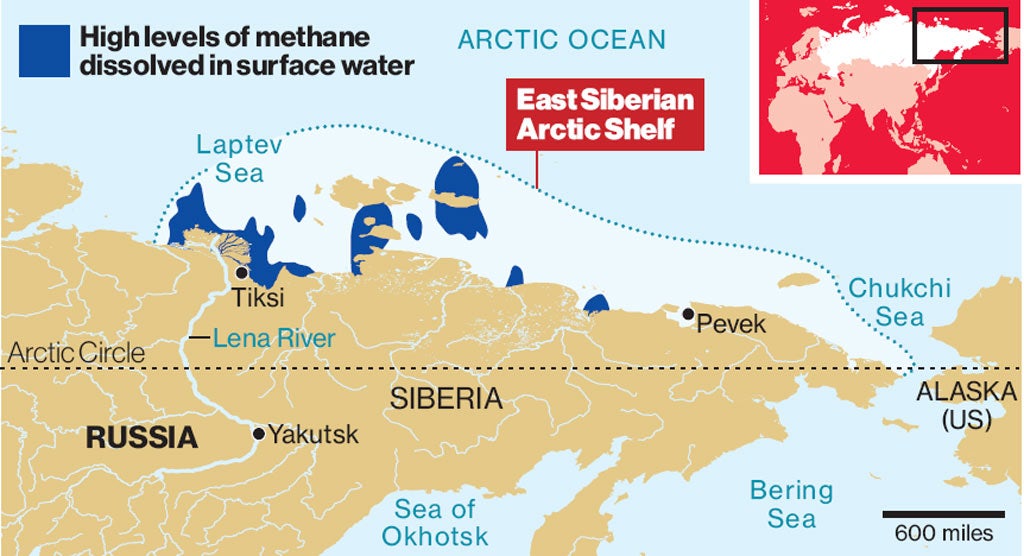

Dramatic and unprecedented plumes of methane - a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide - have been seen bubbling to the surface of the Arctic Ocean by scientists undertaking an extensive survey of the region.

The scale and volume of the methane release has astonished the head of the Russian research team who has been surveying the seabed of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf off northern Russia for nearly 20 years.

In an exclusive interview with The Independent, Igor Semiletov of the International Arctic Research Centre at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, who led the 8th joint US-Russia cruise of the East Siberian Arctic seas, said that he has never before witnessed the scale and force of the methane being released from beneath the Arctic seabed.

"Earlier we found torch-like structures like this but they were only tens of metres in diameter. This is the first time that we've found continuous, powerful and impressive seeping structures more than 1,000 metres in diameter. It's amazing," Dr Semiletov said.

"I was most impressed by the sheer scale and the high density of the plumes. Over a relatively small area we found more than 100, but over a wider area there should be thousands of them," he said.

Scientists estimate that there are hundreds of millions of tons of methane gas locked away beneath the Arctic permafrost, which extends from the mainland into the seabed of the relatively shallow sea of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf.

One of the greatest fears is that with the disappearance of the Arctic sea ice in summer, and rapidly rising temperatures across the entire Arctic region, which are already melting the Siberian permafrost, the trapped methane could be suddenly released into the atmosphere leading to rapid and severe climate change.

Dr Semiletov's team published a study in 2010 estimating that the methane emissions from this region were in the region of 8 million tons a year but the latest expedition suggests this is a significant underestimate of the true scale of the phenomenon.

In late summer, the Russian research vessel Academician Lavrentiev conducted an extensive survey of about 10,000 square miles of sea off the East Siberian coast, in cooperating with the University of Georgia Athens. Scientists deployed four highly sensitive instruments, both seismic and acoustic, to monitor the "fountains" or plumes of methane bubbles rising to the sea surface from beneath the seabed.

"In a very small area, less than 10,000 square miles, we have counted more than 100 fountains, or torch-like structures, bubbling through the water column and injected directly into the atmosphere from the seabed," Dr Semiletov said.

"We carried out checks at about 115 stationary points and discovered methane fields of a fantastic scale - I think on a scale not seen before. Some of the plumes were a kilometre or more wide and the emissions went directly into the atmosphere - the concentration was a hundred times higher than normal," he said.

Dr Semiletov released his findings for the first time last week at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco. He is now preparing the study for publication in a scientific journal.

The total amount of methane stored beneath the Arctic is calculated to be greater than the overall quantity of carbon locked up in global coal reserves so there is intense interest in the stability of these deposits as the polar region warms at a faster rate than other places on earth.

Natalia Shakhova, a colleague at the International Arctic Research Centre at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said that the Arctic is becoming a major source of atmospheric methane and the concentrations of the powerful greenhouse gas have risen dramatically since pre-industrial times, largely due to agriculture.

However, with the melting of Arctic sea ice and permafrost, the huge stores of methane that have been locked away underground for many thousands of years might be released over a relatively short period of time, Dr Shakhova said.

"I am concerned about this process, I am really concerned. But no-one can tell the timescale of catastrophic releases. There is a probability of future massive releases might occur within the decadal scale, but to be more accurate about how high that probability is, we just don't know," Dr Shakova said.

"Methane released from the Arctic shelf deposits contributes to global increase and the best evidence for that is the higher concentration of atmospheric methane above the Arctic Ocean," she said.

"The concentration of atmospheric methane increased unto three times in the past two centuries from 0.7 parts per million to 1.7ppm, and in the Arctic to 1.9ppm. That's a huge increase, between two and three times, and this has never happened in the history of the planet," she added.

Each methane molecule is about 70 times more potent in terms of trapping heat than a molecule of carbon dioxide. However, because methane it broken down more rapidly in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, scientist calculate that methane is about 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a hundred-year cycle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks