DNA tests prove your close friends are probably distant relatives

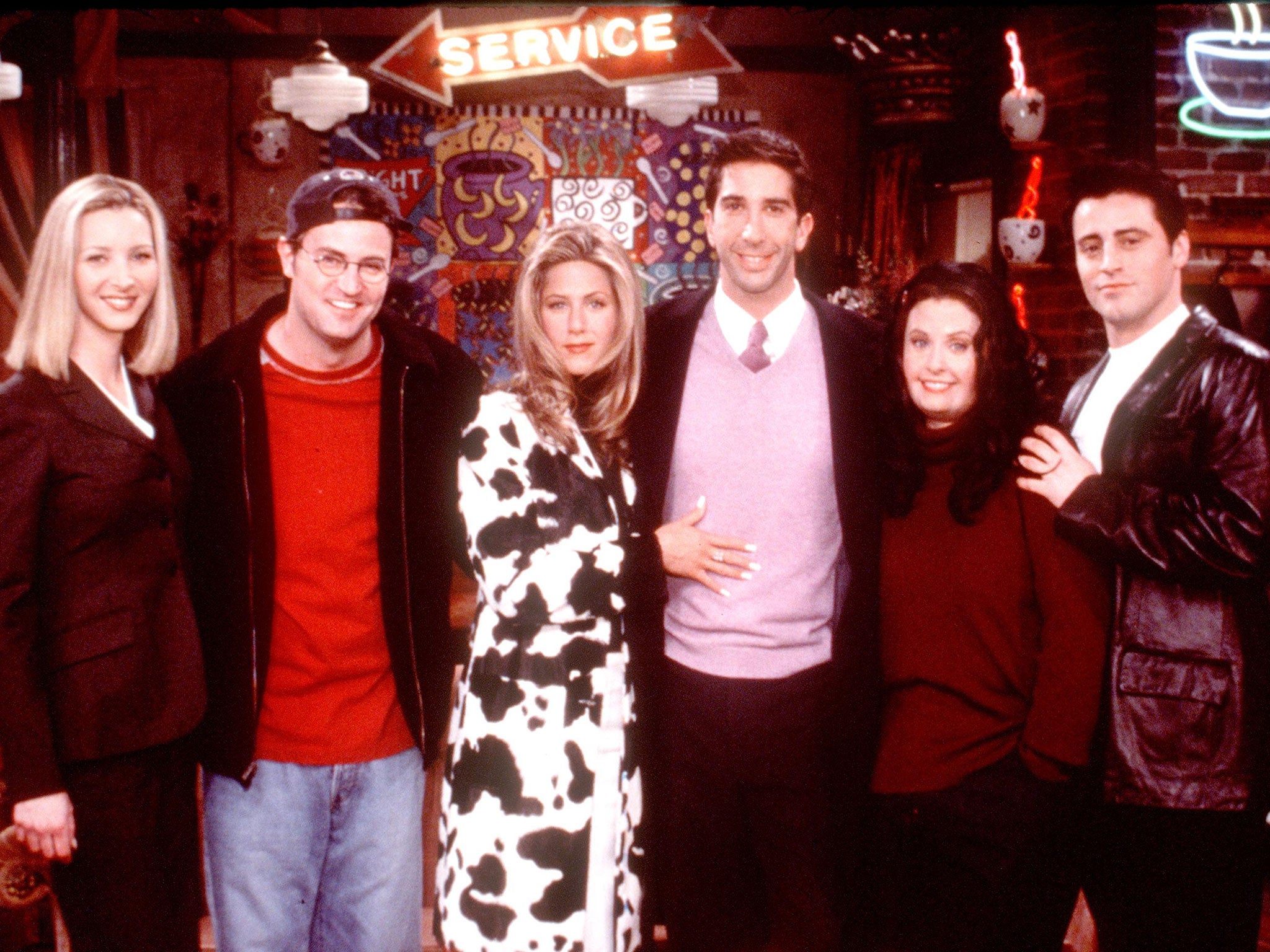

Professor Fowler and his colleague Nicholas Christakis analysed DNA to see how different or similar each member of a pair was to one another

You can choose your friends, but you can’t choose your family, or so says the adage. But scientists have found that by choosing friends we may also be unwittingly choosing the company of distant relatives.

A study into the genetic nature of friendship has found that, on average, close friends are likely to be as genetically related to one another as fourth cousins who share the same great, great, great grandparents.

The findings suggest there is an unexplained mechanism that helps us to choose our friends based on how similar they are to us in terms of their DNA, said James Fowler, professor of medical genetics at the University of California, San Diego.

“Looking across the whole genome we find that, on average, we are genetically similar to our friends. We have more DNA in common with the people we pick as friends than we do with strangers in the same population,” Professor Fowler said.

The phenomenon may have arisen as part of an evolutionary process, he said. “The first mutant to speak needed someone else to speak to. The ability is useless if there’s no-one who shares it,” he said.

“These types of traits in people are a kind of social network effect.”

The research involved genome-wide studies of nearly 2,000 people who were part of a larger, long-term investigation into the factors that influence heart disease and who, as a result, had already had their DNA analysed for the smallest mutations.

Professor Fowler and his colleague Nicholas Christakis of Yale University took pairs of individuals based simply on whether they were friends or total strangers and analysed their DNA to see how different or similar each member of a pair was to one another.

They found that the strangers were quite dissimilar in terms of their DNA mutations, but that the pairs of friends were on average about as related to one another as fourth cousins, a genetic similarity of about 1 per cent of their DNA.

Although relatively small, the difference was still statistically significant, Professor Christakis said. “One per cent may not sound like much to the layperson, but to geneticists it is a significant number,” he explained.

“And how remarkable: most people don’t even know who their fourth cousins are. Yet we are somehow, among the myriad of possibilities, managing to select as friends the people who resemble our kin,” he said.

The findings could not be explained by people tending to make friends with members of the same ethnic group as the heart study overwhelmingly involved Americans of European ancestry, the scientists said.

In their study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Christakis and Fowler suggest that the phenomenon may have evolved as a version of a well-documented feature in Darwinism known as “kin selection”, when closely related animals cooperate to the mutual benefit of the genes they share.

The two scientists argued that friends are behaving as a sort of “functional kin” and that the genetic similarities of modern day friends to one another may have deep evolutionary roots that have in the past aided survival.

“Cues of kinship may foster altruistic impulses and cooperative exchanges with individuals displaying those cues, and it is not hard to imagine that such a system might possibly be extended to preferential (active) friendship formation,” they write in their scientific paper.

The olfactory sense of smell may be one possible way for people to subconsciously judge the genetic similarity of strangers to themselves, they said.

Previous studies, for instance, have shown that women can judge male attractiveness based on smell and this may result in choosing spouses whose immune systems are genetically unrelated, which could serve as a mechanism for avoiding in-breeding, the scientists said.

Christakis and Fowler found evidence to support this idea by showing that friends are most similar in the genes affecting the sense of smell, but they are more dissimilar for the genes that control immunity.

“It is possible that individuals who smell things in the same way are drawn to similar environments where they interact with and befriend one another,” the researchers said.

Perhaps the most intriguing result of the study, they said, is that the genes that are most similar between friends are also the ones that appear to have evolved the fastest over the past 30,000 years.

“It seems that our fitness depends not only on our own genetic constitutions, but also on the genetic constitutions of our friends,” said Professor Christakis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks