Mysterious giant 2,000-year-old rock artworks depicting ancient rituals mapped in detail for first time

Engravings show how people lived and travelled in the region

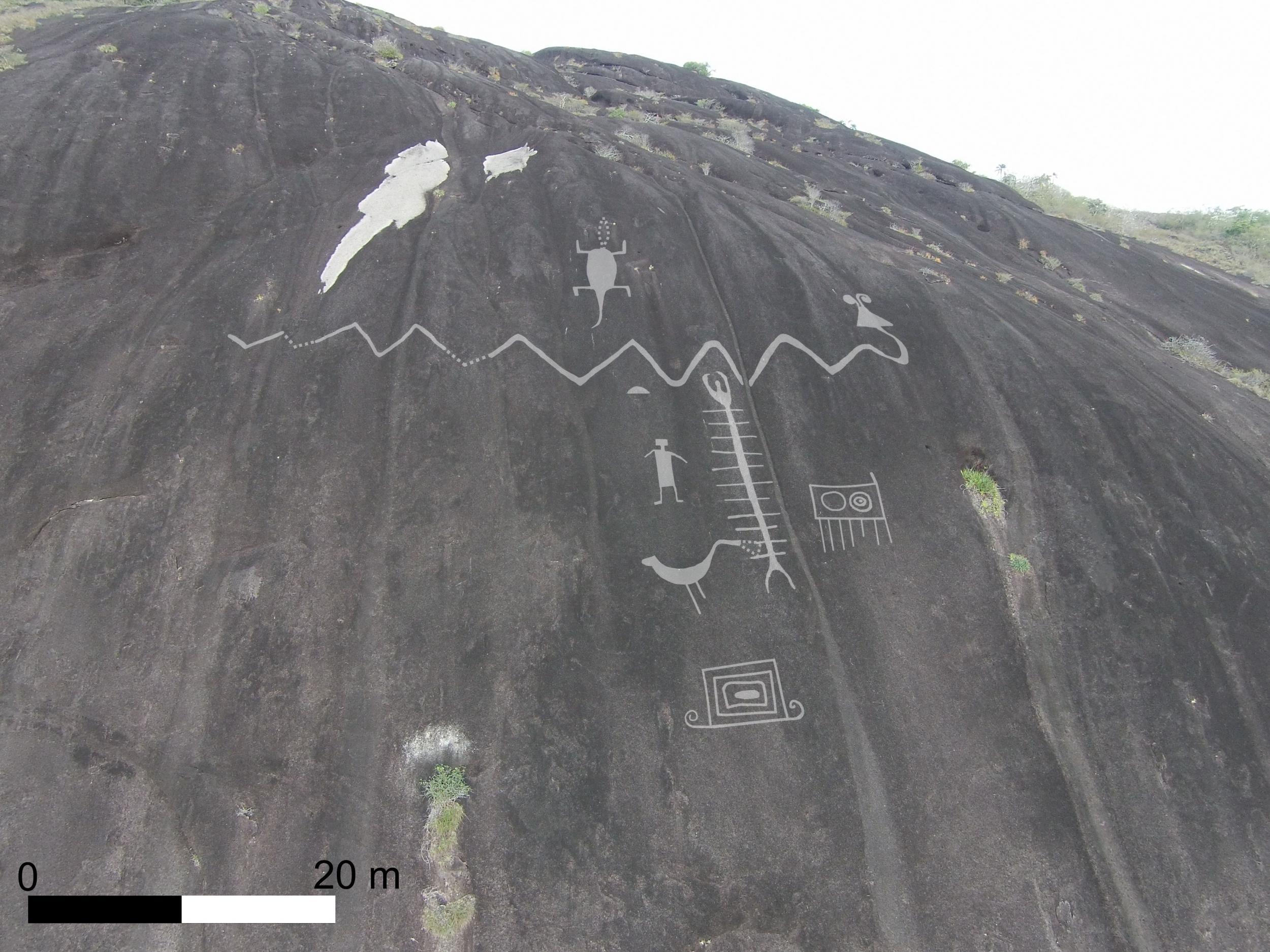

Some of the largest rock engravings recorded anywhere in the world have been mapped in detail for the first time by researchers.

The petroglyphs, scanned by researchers from University College London, depict animals, humans and ancient cultural rituals.

Some of the art, located in the Atures Rapids area of western Venezuela, is believed to be up to 2,000 years old.

One panel, which measures 304 square metres, contains at least 93 individual engravings each stretching several metres across.

An engraving of a horned snake measures more than 30 metres in length.

Using drones, the researchers were able to photograph the engravings, some of which are in extremely inaccessible areas.

Low water levels in the Orinoco River meant more of the art was exposed.

Study author Dr Philip Riris, of UCL’s Institute of Archaeology, said the area was an ethnic, linguistic and cultural convergence zone.

“The motifs documented here display similarities to several other rock art sites in the locality, as well as in Brazil, Colombia, and much further afield,” he said.

“This is one of the first in-depth studies to show the extent and depth of cultural connections to other areas of northern South America in pre-Columbian and colonial times.”

He added the engravings provided a snapshot into ancient lives.

“While painted rock art is mainly associated with remote funerary sites, these engravings are embedded in the everyday — how people lived and travelled in the region, the importance of aquatic resources and the seasonal rhythmic rising and falling of the water.

“The size of some of the individual engravings is quite extraordinary.”

Rock engravings of the Middle Orinoco River have been studied before, but never in this level of detail, which offers researchers new insights into the archaeological and ethnographic context of the art.

Almost all the engravings are affected by seasonally rising and falling water levels in the Orinoco.

Depending on the rain upstream, the relative height of the river also varies annually by up to several metres during the extremes of both seasons.

In one panel, a motif of a flautist surrounded by other human figures probably depicts part of an indigenous rite of renewal.

Researchers believe such performances may have coincided with the seasonal emergence of the engravings from the river before the wet season, when the islands are more accessible and the harvest would take place.

“Our project focuses on the archaeology of Cotua Island and its immediate vicinity of the Atures Rapids,” said principal investigator Dr Jose Oliver.

“Available archaeological evidence suggests that traders from diverse and distant regions interacted in this area over the course of two millennia before European colonisation.

“The project's aim is to better understand these interactions.

“Mapping the rock engravings represents a major step towards an enhanced understanding of the role of the Orinoco River in mediating the formation of pre-Conquest social networks throughout northern South America.”

The research was originally published in the journal Antiquity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks