Stargazing in April: Starry serpents in the sky

The oldest star-pattern is visible faintly this month. Keep an eye out for Hydra, writes Nigel Henbest

Hydra is far from being the most prominent constellation in the sky, but the celestial Water Snake has perhaps the most intriguing history. And it has a strong claim to be oldest star-pattern, dating back to before the Great Pyramid of Giza or Stonehenge were erected.

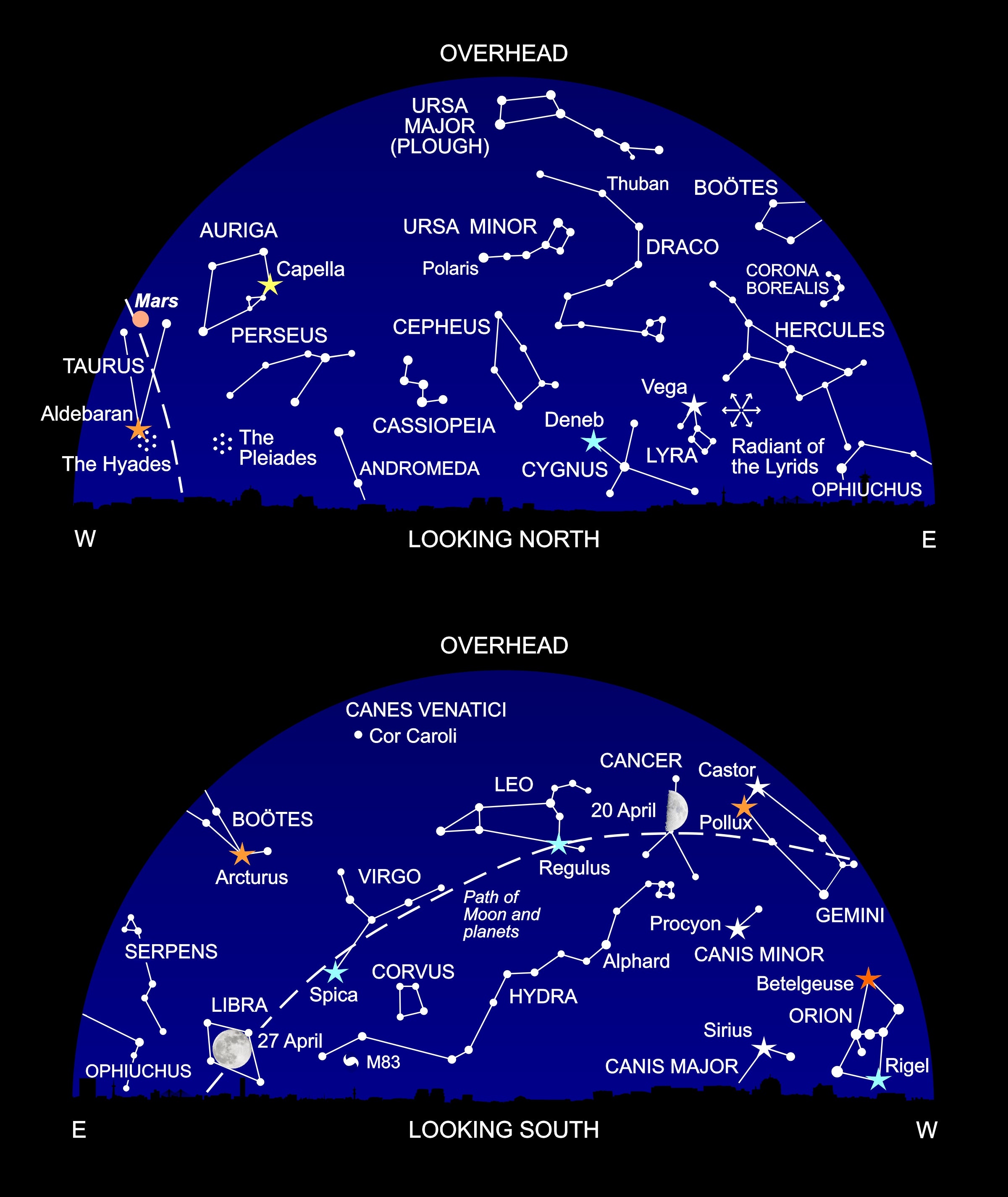

This line of faint stars stretches sinuously below the constellations Cancer, Leo, Virgo and Libra. Its head is a group of stars between Regulus and Procyon, while the reptile’s heart is marked by Hydra’s only moderately bright star, Alphard, an Arabic name meaning “the lonely one”. The only other object of note, if you have a telescope, is the beautiful spiral galaxy M83.

Hydra is the largest constellation and also the longest, stretching more than a quarter of the way around the sky. But why did ancient astronomers connect so many dim stars in a long line, rather than break them up into smaller star groups? This question led two British astronomers, Mike Ovenden and Archie Roy, into a voyage back to the misty dawn of the constellations.

The appearance of the sky changes over the millennia, as the Earth’s axis gradually swings round in space. As a result, different stars successively become our Pole Star, the star lying above the north pole. For us it’s Polaris; but thousands of years ago it was Thuban in Draco (the Dragon).

At the same time, the constellations lying above the Earth’s equator gradually change. Today, the equator of the sky runs from Virgo to Orion. But Ovenden and Roy realised that, if we go back far enough, the stars of Hydra traced out the celestial equator.

Read More:

At that epoch, the constellation of Serpens (the Serpent) – which we can see rising in the east this month – ran upwards from the end of Hydra’s tail towards Thuban, then positioned above the north pole. While Hydra marked the celestial equator, Serpens was the Greenwich meridian of the sky. And both of these constellations – along with Draco, home of the then Pole Star – were named for sinuous reptiles.

What’s most remarkable is the date. While the first catalogue of the constellations was written down in about 350BC, and the star-patterns in the zodiac were defined around 1200BC, the celestial serpents aligned in the sky way back in 2800BC.

The celestial grid of faint stars makes most sense as a navigational aid at sea. At that time, the Mediterranean was dominated by the Minoan civilisation based in Crete. It seems like a wild idea, but the evidence points to Hydra being delineated almost 5000 years ago, by Minoan sailors.

For millennia, the constellation’s shape was passed down by oral tradition until it reached the Greek astronomer Eudoxus, who lived on the shores of the Aegean Sea and listed Hydra in his definitive compilation of constellations.

The Minoan civilisation was devastated by the explosion of the volcanic island of Santorini around 1600BC, possibly giving rise to the legend of Atlantis, the great city that sank beneath the waves. The connection led Archie Roy, with poetic flare, to call our constellation patterns “The Lamps of Atlantis”.

What’s Up

The familiar figure of Orion, the great hunter, who watches over the winter nights, is now slipping away below the western horizon, along with his entourage of bright constellations such as Taurus (the Bull) and Gemini (the Twins).

The southern sky is home to the fainter constellations of spring. Leo (the Lion) rides high, with the Y-shape of Virgo (the Virgin) to its lower left. Below Leo you’ll find the straggling stars of Hydra (see main story), and to its left the bright orange star, Arcturus.

At the beginning of April, the only planet on view in the evening sky is Mars, over to the west: the crescent moon passes nearby on 16 and 17 April. To catch any more planets, you’ll have to wait till after 4am to find Jupiter and Saturn rising before dawn.

But all that changes towards the end of the month, when brilliant Venus emerges from the evening twilight glow. Far outshining all the stars in the sky, the planet of love will grace our skies as a beautiful Evening Star throughout the rest of 2021. In the last week of April, it’s joined by Mercury, around ten times fainter.

There will be shooting stars on the night of 21/22 April, as dust from Comet Thatcher burns up in the Earth’s atmosphere. But don’t raise your hopes too high: bright moonlight will drown out all but the brightest meteors.

Diary

4 April, 11.02am: Last quarter moon

12 April, 3.31am: New moon

14 April: Moon near the Pleiades

15 April: Moon between the Pleiades and Aldebaran

16 April: Moon between Aldebaran and Mars

17 April: Moon near Mars

19 April: Moon near Castor and Pollux

20 April, 7.59am: First quarter moon

21/22 April: Maximum of Lyrid meteor shower

22 April: Moon near Regulus

25 April: Moon near Regulus; Mercury near Venus

27 April, 4.31am: Full moon

Philip’s 2021 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks