The Big Question: What is nanotechnology, and do we put the world at risk by adopting it?

Why are we asking this question now?

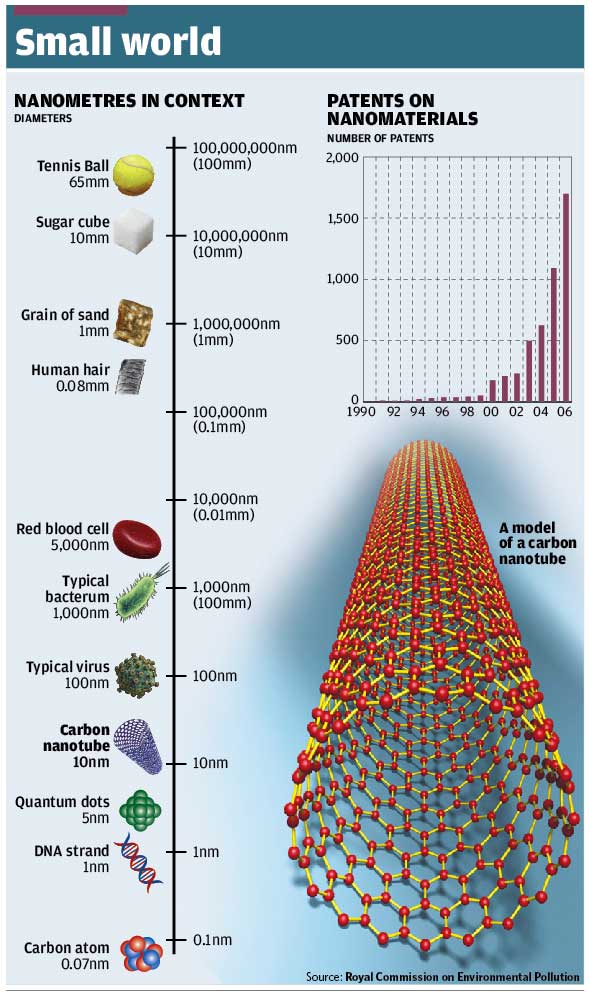

The Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution has just published a report on novel materials and has looked at the case of nanotechnology, which describes the science of the very small. Nanotechnology covers those man-made materials or objects that are about a thousand times smaller than the microtechnology we use routinely, such as the silicon chips of computers.

Nanotechnology derives its name from the nanometre, which is a billionth of a metre. To get some measure of the scale of the materials and devices we are talking about, a human hair is about 80,000 nanometres wide.

Should we be concerned about nanotechnology?

The Royal Commission found no evidence of harm to health or the environment from nanomaterials, but this "absence of evidence" is not being taken as "evidence of absence". In other words, just because there are no apparent problems, this is not to say that here is no risk now or in the future. The Commission is concerned about the pace at which we are inventing and adopting new nanomaterials, which could result in future problems that we are ill-equipped to understand or even detect with current testing methods.

The Commission's broad conclusion is that the speed of development in the field of nanotechnology "is beyond the capacity of existing testing and regulatory arrangements to control the potential environmental impacts adequately". In summary, not enough is known about the effect that these very small devices and materials will have on human health or the environment, and the tests that could tell us about them are either not available or not being used.

What is covered by the term nanotechnology?

There are about 600 consumer products already on the market that use nanotechnology. They include nanoparticles of titanium dioxide added to sun creams to make them transparent instead of white, or tiny fragments of silver that are added to sports equipment to make them odour-free – the silver acts as a powerful anti-bacterial agent. Nanomedicine are also being developed to fight cancer and other fatal diseases.

So nanotechnology is not all bad, but the point is, the ability to make such fine particles and materials is getting better all the time. As a result, many companies are taking up the opportunity of using them in products with little or no knowledge of how they may have an impact human health or the environment. The silver particles in sports clothing might end up killing off bacteria in sewage systems for example.

Is everything at the nano scale artificial?

No. A molecule of DNA is an example of a natural nano-scale substance with the diameter of its double helix structure measuring about one nanometre. A typical virus, meanwhile, is about 100 nanometres wide. This is the range of nanoscale objects in nature that roughly covers the field of synthetic nanotechnology. So the human body and nature at large is well used to nanoscale objects and materials.

Why might there be risks?

One of the chief concerns is that when you make something very small out of a well known material, you may actually change the functionality of that material even if the chemical composition remains the same. Indeed, the Commission emphasised this point: "It is not the particle size or mode of production of a material that should concern us, but its functionality."

Take gold, for instance, which is a famously inert substance, and valuable because of it. It doesn't rust or corrode because it doesn't interact with water or oxygen, for instance. However, a particle of gold that is between 2 and 5 nanometres in diameter becomes highly reactive. This is not due to a change in chemical composition, but because of a change in the physical size of the gold particles.

How can this result in a change of function?

One reason is to do with surface area. Nanoparticles have a much bigger surface area-to-volume ratio than microparticles a thousand times bigger. It is like trying to compare the surface area of a basketball with the combined surface area of pea-sized balls with the same total weight of the single basketball.

The pea-sized balls have a surface area many hundreds, indeed thousands of times bigger than the basketball, and this allows them to interact more easily with the environment. It is this increased interactivity that can change their functionality – and so make them potentially more dangerous to health or the environment.

"As many chemical reactions occur at surfaces, this means that nanomaterials may be relatively much more reactive than a similar mass of conventional materials in bulk form," the Royal Commission said. This suggests that the emphasis on weight alone in terms of toxicity thresholds may not apply for nanomaterials, it added.

Are there precedents?

The Commission cites several examples of health problems caused by the introduction of novel materials. Asbestos, for instance, was an infamous example of a material that provided tremendous benefits as a fire retardant, but when asbestos fibres were inhaled, it resulted in highly malignant cancer mesothelioma.

Lead additives in petrol have been linked with harmful effects on children's mental development, supposedly inert gases called chlorofluorocarbons in refrigeration are now known to have depleted the protective ozone layer of the atmosphere, and the antifouling agent tributyltin in paint has been found to change the sex of marine organisms. More recently, tiny particles called PM10s in exhaust fumes have been linked with lung and heart problems caused by pollution.

Where did the idea of these dangers emerge?

The first scientist to see the potential of nanotechnology was the American physicist Richard Feynman who gave a famous 1959 lecture to the American Physical Society entitled "there is plenty of room at the bottom".

Although it was Feynman who first talked about the potential advantages of technology on the small scale, it was an American engineer and author called Eric Drexler who coined the term "nanotechnology" in his 1986 book Engines of Creation. It was also Drexler who first warned of the risk. He described a future in which tiny, self-replicating robots would take over the world – a view he has since disowned. But that did not stop Michael Crichton building on the idea in his novel Prey, which portrayed a future threatened by minuscule, self-replicating machines that could devour the world in a form of "grey goo".

More recently, Prince Charles has spoken out about the potential dangers of nanotechnology and his concerns led to a scientific investigation by the Royal Society, which concluded that there is serious cause for concern. It recommended that the Government should take action by funding research into the potential risks.

Is the Government taking this issue seriously?

It says that it is. It is working with European bodies to ensure that consumers are properly protected against products and materials containing nanotechnology. The Government has also promised a public dialogue on the subject. However, the real issue is whether it can actually fund the research that can assess the risks and work out what needs to be done – if anything.

Should the Government call a moratorium on nanotechnology?

Yes...

* The risks are simply too great to carry on business as usual until we know more

* We have managed perfectly well so far without nanotechnology, so why take the chance?

* If there is any doubt at all, it would do no harm to call a temporary halt until we know more

No...

* We already enjoy too many benefits from nanotechnology to be able to straightforwardly stop now

* The risks are hypothetical and it would be a mistake to stop without harder evidence that the risk is real

* The potential benefits that are just around the corner far outweigh any possible risks

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks