The lost girls: It seems that the global war on girls has arrived in Britain

Worldwide, gender selection – including the abortion of female foetuses – may account for a shortfall of up to 200 million girls. The UK is no longer immune

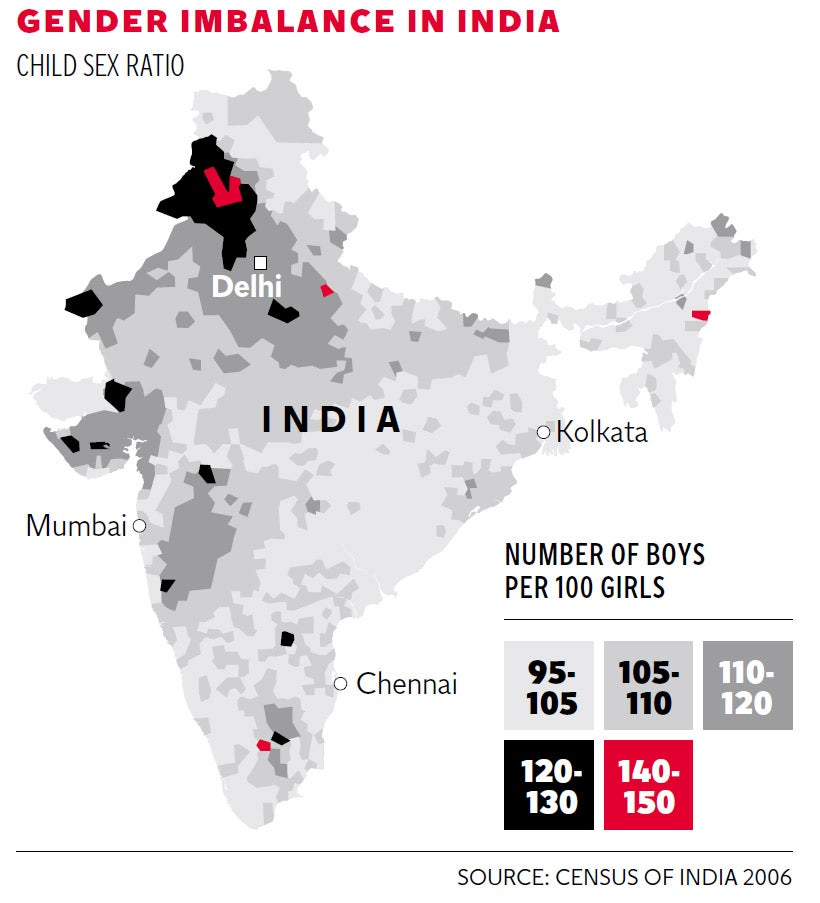

The selective abortion of female foetuses is almost routine in many parts of the world where it has contributed to significant shifts from the natural 50:50 sex ratio in favour of boys. In some parts of India and China, for instance, there are now almost one-and-a-half times as many boys as there are girls.

Demographic experts and economists have long warned about the "global war on girls" but many politicians in Britain - and other western nations - had believed it to be a foreign phenomenon that did not affect the gender make-up of the UK population.

Only last May, the Department of Health published its own study into the sex ratio of children born in Britain to foreign-born mothers. It came to the reassuring conclusion that there was little or no evidence that sex-selective abortions were taking place to any significant extent in this country.

"The UK gender ratio is 105.1 male births to 100 females and is well within the normal boundaries of populations. When broken down by the mothers' country of birth, no group is statistically different from the range that we would expect to see naturally occurring," its report concluded.

Earl Howe, the minister responsible for overseeing the health department's investigation, was even more unequivocal. In answer to a Parliamentary question in June, Earl Howe said: "We do not believe that there is any evidence that this is happening in the UK."

However, the health department did not carry out a powerful enough statistical analysis to uncover any significant gender inconsistencies due to sex-selective abortions. Specifically, the department's Analytical Team did not look at the birth ratios of second or third-born children of immigrant mothers or fathers.

Experts in this area say that if you are looking for selective abortions based on gender, the way to do it is to look at whether having an older daughter is likely to affect the sex of a younger child. In other words, do you see more boys than expected among the younger siblings of older daughters? This is very unlikely without the selective abortion of female foetuses.

Studies in Canada and the United States have shown that parents from certain immigrant backgrounds are more likely to have a boy as their second child if their first born is a girl, compared to families where the first child is a boy. This boy-bias was even more pronounced among the third born of three-child families where the two eldest are girls.

The Canadian study, based on the country's national census data, also showed that the problem was not isolated to first-generation immigrants. In fact, second generation parents born in Canada were more likely to use sex-selective abortions to ensure that a second or third child was a boy, the study concluded.

The normal sex ratio at birth is 1.05, meaning that there are about 105 baby boys born to every 100 baby girls. This natural bias in favour of boys is believed to counteract the slightly higher risk of premature death in boys compared to girls. But if the sex ratio begins to rise above 1.08, statisticians believe something else must be influencing the appearance of the extra boys.

Some people have argued, for instance, that certain ethnic groups are just more likely to give birth to baby boys than other ethnic groups. However, there is no firm evidence to suggest that the natural 1.05 sex ratio at birth varies between ethnic groups around the world.

Nevertheless, there is convincing data to show that sex ratios have been artificially manipulated to an extraordinary degree within certain cultures in some parts of the world. In many cases, this is primarily due to widely-available abortions and the widespread use of gender testing, such as ultrasound scanning after the first trimester (12 weeks) of pregnancy, which can determine the sex of a foetus with an accuracy of 99 per cent or more.

In parts of India, notably the relatively affluent north-west states of Punjab and Haryana, the sex ratio of certain age groups is now about 1.2 or above - meaning there are 120 boys for every 100 girls. While in some parts of China, especially those where the Han Chinese form the main ethnic group, sex ratios among children have reached as high as 1.4 or even 1.5 - one-and-a half times as many boys as girls.

In both these regions of the world, the vilification of girls is deeply engrained within some elements of the population. A Punjabi proverb, for instance, likens raising a daughter to watering your neighbour's garden, while an old Chinese saying states that it is better to have one crippled son than eight healthy daughters.

The greater value placed on a son in many parts of the world often has deep cultural roots. In the case of India, it likely involves the dowry system - girls are just more expensive - while in China, which has practised a "one-child policy", it may concern fears of being unsupported in old age, or of the family "line" dying out, which is anathema to the Confucian idea of cultural heritage.

However, being unhappy with having daughters is evidently not shared by similar cultural or religious traditions. Japan, another Confucian culture, has a normal sex ratio at birth, as does the largely-Hindu state of Kerala in south-west India, where women also enjoy one of the highest literacy rates in the country (and where property can be inherited through the maternal line).

A 2006 study by Indian scientists, published in The Lancet, estimated that during the previous two decades about 10 million female foetuses had been aborted in India following ultrasound scans to determine the sex of an unborn baby - ultrasound machines have been used in almost every maternity clinic in India since 1990.

Abortions based on sex-selection are, however, just the latest manifestation of the war on girls, leading at its most heinous to the deliberate abandonment or infanticide of female babies. As recently as 2003, a study in the British Medical Journal found that girls in India were nearly twice as likely as boys to die in the first year of life.

More recently, the Council of Europe has warned that sex-selective abortions appear to be responsible for worrying changes in the sex ratio of boys to girls in Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. It has warned that gender imbalances "are like to create difficulties for men to find spouses, lead to serious human rights violations such as forced prostitution, trafficking for the purpose of marriage or sexual exploitation, and contribute to a rise in criminality and social unrest".

Imbalances in the sex ratio of some parts of the world, notably South Asia, West Asia and North Africa, are nothing new and predate the use of ultrasound machines. In 1990, it led Amartya Sen, the Indian-born Nobel economist, to calculate that some 100 million women had already gone missing in the world - a figure that must have easily doubled since then, aided by gender-selective abortion.

"These numbers tell us, quietly, a terrible story of inequality and neglect leading to the excess mortality of women," Sen wrote in a seminal essay on the disappearing sex published nearly a quarter of a century ago.

"If this situation is to be corrected by political action and public policy, the reasons why there are so many 'missing' women must first be understood. We confront here what is clearly one of the more momentous, and neglected, problems facing the world today."

Since Sen wrote this warning nearly three decades ago, the problem of the world's missing women has continued to be neglected. Now, the global war on girls can truly be said to have arrived in Britain.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks