‘I am not a monster’: The Kray twins’ hitman on how he survived a life of crime

‘Godfather of British crime’ Freddie Foreman speaks to Dan Bilefsky about turning down the Hatton Garden heist, what the Krays were really like, and how he’s the ‘last one left’

It was Easter Monday, and five thieves – three wearing balaclavas, two in monkey masks and all of them armed and speaking with fake Irish accents – had broken into a security company in east London.

When one of the guards, who was blindfolded and tied to a chair, hesitated to reveal the vault’s combination, the gang put lighter fluid under his nostrils and threatened to light a match, one of the thieves, Freddie Foreman, now recalls.

The criminals sped away with £6m at the time of the heist in 1983 – the largest cash robbery of the era.

Reminiscing about the episode, Foreman, the self-described “Godfather of British crime”, now 87 years old, says the break in at Security Express was humane.

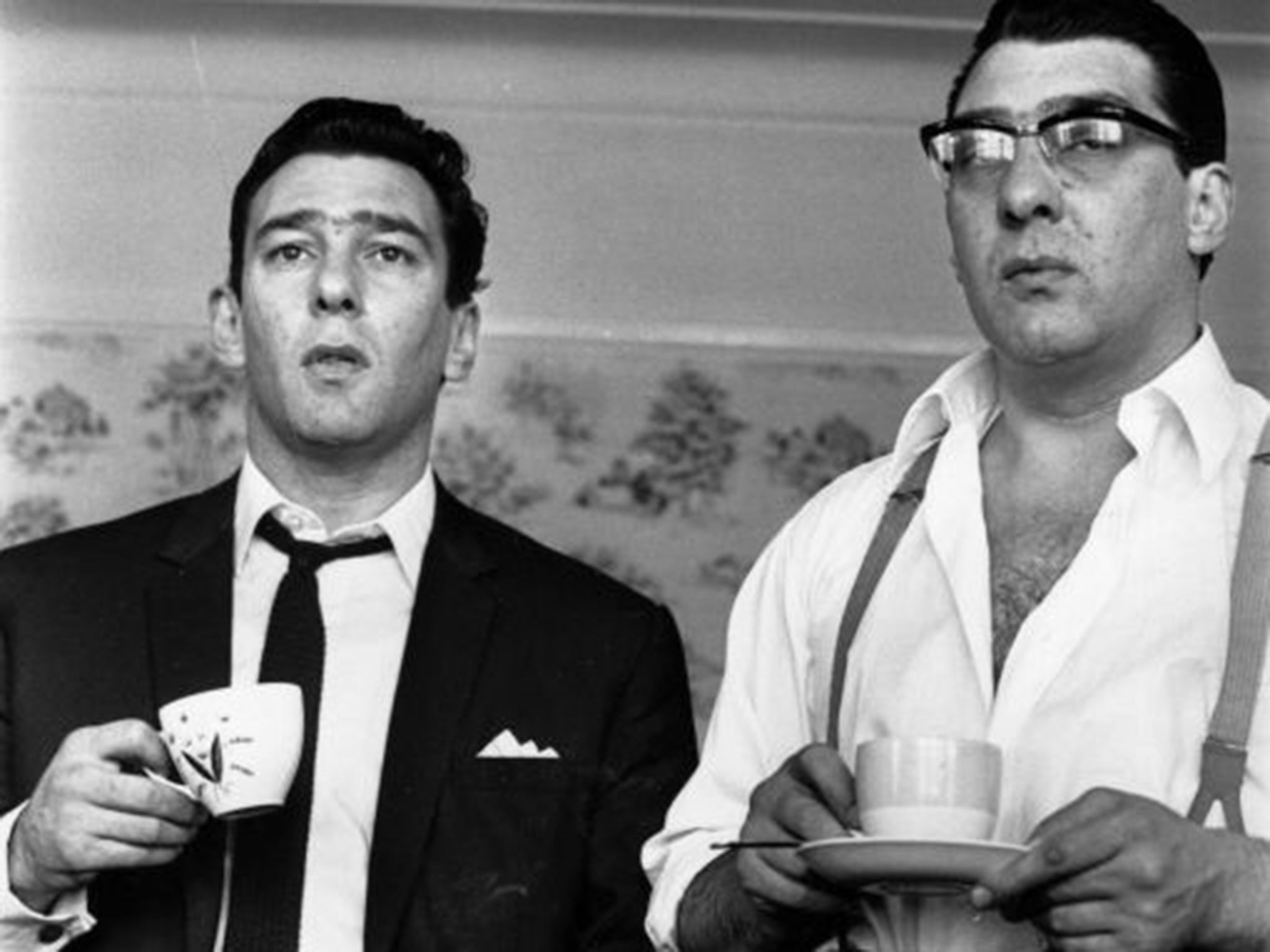

“We gave the guards tea, and no one went to hospital, and I am proud of that,” says Foreman, a stocky man whose grandfatherly demeanour is hard to square with his former incarnation as a freelance enforcer for the Krays, the notorious identical twin gangsters who stalked London in the 1950s and 1960s.

Apparently eager for company, Foreman is instantly welcoming when I knock on his door, unannounced, at a residence for seniors in Maida Vale in west London. Dressed in a grey jogging suit, he pours two large glasses of wine.

The visit is research for my book The Last Job, which tells the story of the Hatton Garden heist, an audacious 2015 burglary in London’s diamond district. Over Easter weekend, a group of ageing thieves stole nearly £14m in gems, gold and cash from a series of safe deposit boxes, climbing down an elevator shaft with diamond-tipped drills and busting through a concrete wall about 20in thick.

I tell Foreman that I’m hoping he can shed some light on what would possess a group of geriatric criminals to come out of retirement. “Money,” says Foreman, a born raconteur who speaks in long paragraphs peppered with Cockney slang. “And the thrill of once again being part of the game.”

He also reveals a secret: he nearly went on the Hatton Garden job himself. He says the gang tried to recruit him and he regrets not going. At the time, he was 82. “I was too old to fancy going to work, but it would’ve been one last roll of the dice,” he says.

Foreman’s home is cramped, but he doesn’t need much room after more than a decade of living in a prison cell, “my every movement watched by screws”, he says. He is sprightly in manner, but sometimes uses a walking stick, and two strokes and triple bypass surgery have slowed him down. He still works out, using two purple dumbbells.

A shelf is crammed with memories of his former life: a black-and-white portrait of him as a scrappy 17-year-old bare-knuckle boxer, a photograph of the Kray twins. There are stacks of gangster films, along with a biography, The Dark Charisma of Adolf Hitler.

Paul Van Carter, director of Fred, a chilling 2018 documentary about Foreman’s life, calls him the last living legend among the “old school London heavy gangsters” who came of age on the streets of the British capital after the Second World War. “I consider him a businessman who operated in the criminal world,” Van Carter says. “He was charming, intelligent, loyal to his friends and as feared as he was respected.”

Foreman’s journey from “Brown Bread Fred”, (“brown bread” being Cockney rhyming slang for “dead”), to retired pensioner has been variously marked by hardship, opulence, menace and a canny instinct for survival.

When I was 18 and my mother discovered my revolver in my bedroom closet, she told me I was going to end up hanging from a noose

One of five sons of a taxi driver and a housewife, the violence and poverty of his childhood during the war helped form him. “I remember being blown out of my bed by an explosion and seeing children’s bodies on the streets,” he says.

“I didn’t have an education,” he adds. “If I had, my life could’ve turned out differently.”

Foreman’s criminal career began in the 1940s at age 16 when he lived in Battersea, in south London, then a tough neighbourhood. Handsome and strong, he says he apprenticed with a band of female thieves, who stuffed their bloomers with stolen mink furs, jewellery and clothing.

“They liked me, they were nice birds, and I became their protector,” he says. “When I was 18 and my mother discovered my revolver in my bedroom closet,” he adds, “she knew what kind of boy I was. She would say, ‘Fred Foreman, you’re going to end up hanging from a noose.’”

He said he had tried to go clean by working in a meat market but he had hungered for “easy money”. By the 1950s, he says, he had graduated to stealing washing machines and televisions.

His real entry into the underbelly of London crime came in the 1960s when he was recruited by the Kray brothers, under whose tutelage he earned another of his nicknames: the Undertaker. He expresses regret about ever getting involved with the Krays.

He says it was a perilous but glamorous world; Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland visited the brothers’ nightclubs in London’s West End. Soon, Foreman was ruling over a swath of south London and owned pubs, betting shops and a nightclub called Hamilton House. “It was posh – people came from all over London,” he says.

But he also had other duties. When an associate of the Krays, Frank “the Mad Axeman” Mitchell, became a liability after the brothers helped spring him from prison in 1966, he was lured into a van and shot. “He was going to shoot six coppers; I should get a medal,” Foreman says of Mitchell. He was acquitted of the killing because of a lack of evidence, including the body, which Foreman says was dumped in the English Channel.

On another occasion, when his philandering older brother George was shot in the groin by the irate husband of one of George’s girlfriends, Foreman says he set out for revenge but mistakenly killed someone else.

Violence, he stresses, was a sometimes necessary and unfortunate occupational hazard, but it was never an end in itself. His main motivation for crime, he says, was that he had a wife, Maureen, and three children to support. “There is no greater dishonour than not being able to support your family,” he says. “I am not a monster.” He eventually separated from Maureen, who died several years ago.

In the late 1970s, Foreman moved to the United States, where he ran a vending-machine business in Allentown, Pennsylvania. But the lure of crime cut short his American dream. He was tapped for the Security Express job, he says, and he wanted a piece of the action.

After participating in the robbery in 1983, Foreman escaped to the Costa del Sol in Spain, known at the time as the “Costa del Crime”, because the tourist region had attracted so many criminals.

“I lived in a four bedroom villa,” he says, “between Marbella and Puerto Banús.”

“There was sun and sangria and birds. I would still be there if I could,” he adds wistfully.

But his years on the run came to an end in 1990, when he says he was lured to a Spanish police station and arrested. He recalls how he tried to punch and kick his way out of the police car as it sped by the beach, on the way to the airport, and that he was “drugged like an animal” before eight police officers bundled him onto a plane.

Foreman was never convicted of the Security Express robbery, but he was sentenced to nine years for handling stolen property. All told, he spent 16 years in prison for various crimes, an experience he called a “living hell”.

Now, Foreman lives a quiet life, sharing roast beef dinners with the other older residents in his building. He laments that his sons never visit. He wishes he could spend more time with his eight grandchildren. He lives off the proceeds of his books, including an autobiography called Respect.

Old friends recently came by to celebrate his 87th birthday, but most former members of what he calls his “firm” are dead.

“Almost everyone is gone,” he says, pointing to a black-and-white photograph showing head shots of former Kray associates, including one who was shot in the leg by Reggie Kray in front of his wife and children.

“I am the last one left,” he adds. “I guess I did something right.”

© New York Times

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks