Bradford City stadium fire: The untold stories of the 1985 fire that devastated Valley Parade

Thirty years after football's 'forgotten tragedy', the truth of what exactly happened when 56 people died in a fire at Bradford City's Valley Parade stadium remains elusive

"Thank you. Thank you for telling this," said the woman, who was perhaps 60 or so, to one of the young people whose stage play, based on football's Bradford disaster, had just concluded on the small theatre space behind her. And only after she had gone – vanished into the kind of warm Bradford Saturday night on which wives, children, parents and friends first learned that they were the bereaved, 30 years ago next week – did the significance of her gratitude become clear. She was Hazel Greenwood – the mother whose children, 13-year-old Felix and 11-year-old Rupert, had been ushered away from the flames of the stadium fire all those years ago by a traffic warden, seeking to shelter them under his tunic. He and the children all perished, along with the boys' father. The children were still nestled under the warden's thick overcoat when they discovered them.

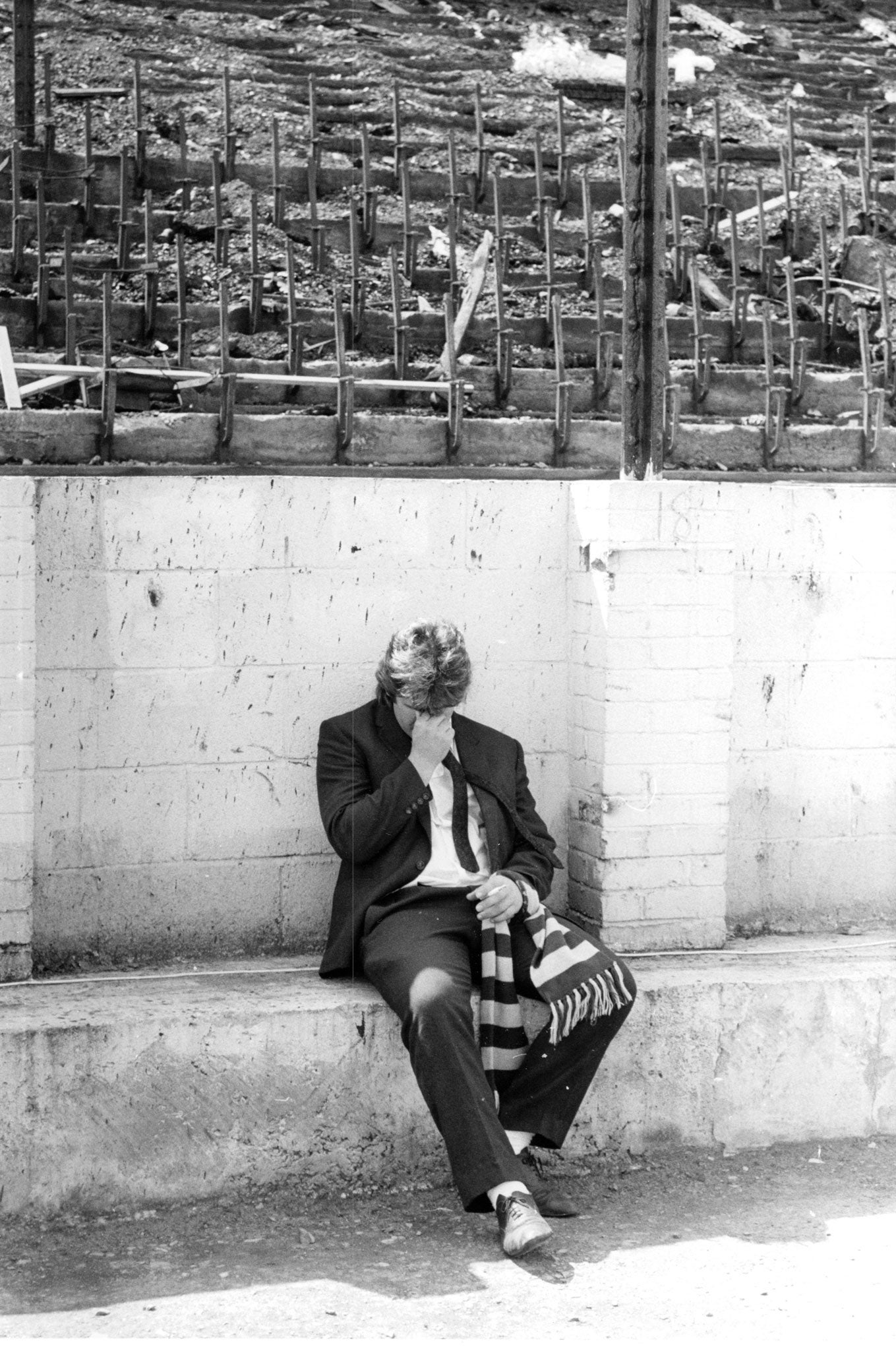

This is the kind of understated remembrance we have seen in Bradford these past few months, at the onset of another significant anniversary of the 1985 fire which tore across the local football club's old wooden main stand, reducing it to a collapsing inferno in a mere four minutes and claiming 56 lives. The play reflects that it had been "the Yorkshire way" not to make a fuss, to bear a loss and move on. And so it has been that while Liverpool supporters' refusal to accept the received narrative of Hillsborough – the stadium disaster 40 miles north across Yorkshire in which 96 died – has made it a source of anger and liberation at the heart of the national consciousness, Bradford became the forgotten tragedy.

The play, entitled simply The 56, does not seek to make melodrama out of that 11 May afternoon at Valley Parade, when fans arrived to celebrate Bradford's promotion from the Football League's division 3. The scriptwriters' hours of interviews with those caught up in the horror are distilled into the narratives of three survivors, and the casual horrors of what befell football supporters that day are all in there. The men with no hair feeling the searing pain first; supporters entering hospital with their hands melted to their heads by the asphalt which has leaked from the stadium roof; a fan's trilby hat igniting. And so, too, is the black tragicomedy which can exist at the boundaries. The unheroic obstinacy of the woman who refused to leave without her handbag "because my teeth are in it." Some laughs puncture the rapt silence of the 75 minutes at Bradford's Alhambra theatre studio. So do the sounds of some of those 150 people present, packing the little theatre's benches to capacity, needing to leave the dark space and take a moment to recover themselves. A half dozen walked out. They all ventured back.

The extraordinary part of all this is that this testimony has barely been heard. Danni Phillips, the young London Academy of Music & Dramatic Art actor who spent hour after hour listening back to the scriptwriters' interviews in preparation for her beautifully observed role in The 56, hails from South Yorkshire, half an hour down the M1 and her father played football for Halifax Town. "But I'd never heard of the Bradford disaster until I auditioned for this," she says. "That made me angry: that people don't know about this."

That certainly changed when Martin Fletcher told his story. His afternoon intersected with that of Preston, who was in an ambulance on his way to St Luke's hospital to be treated for burns when a 12-year-old was bundled aboard, concerned only at the moment to know "how did Leeds United get on" that day. The boy – Fletcher – discovered soon enough how boundlessly and profoundly life-affecting the afternoon would prove to be. He lost his father John, 34, his 11-year-old brother Andrew, uncle Peter, 32, and grandfather Eddie, 63, in the fire. Only now, in 56: The Story of the Bradford Fire (Bloomsbury, £16.99) has he completed a 15-year quest to challenge history's interpretation of why the fire broke out.

Even the received wisdom is enough to make you rage against football's breathtaking complacency: the same complacency which would turn the terrace at Hillsborough into a killing ground, four years later. The Valley Parade fire took hold, it has always been said, because a match must have been dropped into the reservoir of rubbish in the dark cavity beneath the main stand's seats. Down there in the blackness lay tissues of debris which were testament to the ramshackle stadium's neglect. A charred copy of the local paper from Monday, 4 November 1968, was among the litter. That was the open and shut case, the inquiry into the disaster chaired by Sir Oliver Popplewell, a High Court judge, concluded. And Bradford seemed happy with it: five days of testimony, a 27-page report and everyone moved on. There was no appetite for a re-enactment of events, such as that which Dublin embarked upon when a fire at the Stardust nightclub fire in Arcane claimed 48 lives in 1981. Or for a full-blown 91-day inquiry like the one which investigated the 1987 fire at London's King's Cross St Pancras Tube station, though Bradford claimed twice as many lives.

It was Fletcher's mother, Susan, who had always said that she did not believe the fire was an accident and who talked of the other blazes at businesses owned or linked to Stafford Heginbotham, the Bradford City chairman of the day. There actually used to be an old saying in Bradford: "If you see smoke go up in Bradford after 6pm, that'll be one of Stafford's." Fletcher's dogged attempts to demonstrate whether that was just urban rumour included poring over 20 years of local newspaper reports and the business history of Heginbotham. He established that there had been eight other fires at businesses owned by or associated with the entrepreneur, who > died in 1995, aged 61. "It seemed that this should at least have been examined," Fletcher says. "When I read the Popplewell transcripts I could see they were processing 10-15 witnesses a day. That was nothing compared with the time it took to interview witnesses in the Hillsborough Inquiry."

The Independent Magazine's own investigations, at the National Archive at Kew, bear out the nagging suspicions Fletcher always had. The largest volume of evidence stored there relates to the Department of the Environment's Fire Research Council – the body responsible for providing scientific evidence for Popplewell. The director of that organisation, Dr David Woolley, was interviewed for just two hours by the inquiry team, and his private papers reveal his desperate rush to assemble information into a report for Popplewell. "Yes," he told the inquiry when asked if he was "cautious" about the conclusion he had made about a match causing the fire. "We were concerned there might be, because of the rapidity of the fire, a mechanism unknown to us." Reading back the transcript in a 21st-century, Hillsborough Inquiry environment you expect this to be the moment when Popplewell pushes Woolley to elaborate. "What kind of 'mechanism'?" or "How unusual was that degree of rapidity?" Instead, there is nothing. No follow up question. "Yes you've already told us you were concerned," the inquiry's QC effectively says, before he moves the conversation along.

The files show how the possibility of arson was not even touched upon or tested. They reveal how experienced scientists were clearly astonished by how the spread of the fire could have been so rapid. "Storage of paint implicated but no evidence of storage beneath the stand. Nothing surprising in the construction of the stand to give this rate of fire growth," Woolley writes in an untitled script which appears to be his own notes from the first day of Popplewell's Inquiry. And there are also repeated references to the smell of burning plastic. Police present in the vicinity of seats I142 and J142, where the fire was adjudged to have first taken hold, noticed it. There was talk of "a raincoat smell" about 15.40pm that afternoon, as the fire took hold. Woolley's notes again: "Many referred to the smell of burning plastics." These are the kinds of loose ends which would now be investigated to the end of the earth by the Hillsborough team. But it is Bradford, so they are just lying there, dormant, on the file, along with the question of the nine Heginbotham fires.

As Fletcher's investigations have given his book a huge profile, so its subtler components have in many ways been overlooked. Above all else, it is a beautifully observed and incredibly detailed memoir of a son's relationship with the father he lost at the age of 12. The father whose attempts to make him a Bradford City fan he mischievously tried to resist, especially after the family's relocation to the detached surrounds of East Bridgford in Nottinghamshire turned the boy into a Nottingham Forest fan. The father whose burgeoning success as a metals stockholder, driving a BMW 323i, took him a long way from his roots, selling coach trips to Mablethorpe. ("And Dad being Dad, he blagged it all like a dream.")

This early part of the narrative is so readable that you wonder how Fletcher, a qualified accountant, did not wind up as a writer. Or as a football commentator for that matter. He was evidently very successful when his mother's acquaintance with local Bradford broadcaster Tony Delahunty – whose commentary of the fire is part of many Bradfordians' recollections – helped fix him some work experience, as a 14-year-old. The CNN sports correspondent Alex Thomas was a school friend and he always asked Fletcher why he didn't have the ambition to make a go of it in that world. It's hard to avoid the sense that Fletcher might have done, had it not been for that fateful May afternoon, which took away so many of the buttresses of his life.

He and his mother rattled around in the beautiful detached Nottingham home afterwards and the place "was almost mocking you, like the birds in the trees," he says. "The family photographs seemed to mock you, too. My mum said at the time of the Hillsborough Disaster, when it all came home to me, you're angry and the hate is eating you inside out."

It's why he gravitated to London and the enclosed spaces, moving to Brixton when his first base became gentrified. We talk in the anonymous surroundings of his publisher's, in Bloomsbury's Bedford Square.

"I feel like I've been in my 20s for years," he says and his life now – south-west London flatshare, single professional – seems to reflect the world of a restive soul, struggling for an anchor. Bradford played its part in that. "I became an adult overnight at 12 and I'm still there," Fletcher says, and you wonder what's next, now that the book which has become his life's work is published.

Some of those back in Bradford have not welcomed his turning over of the stones. Fletcher's appearance on BBC regional news programme Look North looked like an inquisition, with playback in his headphones as he spoke from a London studio contributing to the difficulty. The local Bradford Telegraph and Argus has found many voices to challenge his testimony, too. The city has seemed to want it to remain the forgotten disaster, though for many, the sense of what-might-have-been is too acute to want to block out the past. It's certainly how Mumtaz Ibrahim feels about the day when, as a newly married 20-year-old, she thought her young husband had been killed in the flames.

"I was out shopping in Bradford and he had gone to the match," she says. "The rumours of the fire came slowly and took hold slowly but when things became clear, I threw down my bags and ran. Ran. Ran home and put the television on." But Ms Ibrahim saw her husband on her TV set, on the Valley Parade half way line, helping stretcher some of the injured away to safety. "I wept with joy," she says. "So yes, it's right that these old questions be asked now. It's right to know why it happened." No, argues her husband, insulated as he was from that momentary horror his wife felt. "Why is it coming out now? It was 30 years ago. It's gone," he says.

It is Mrs Ibrahim's sentiment which seems to be most prevalent in Manningham, the British Asian district bordering Valley Parade, where many locals took injured and traumatised people into their homes that day. Those who helped are reluctant heroes now. "We did not know the fullness of what was happening but we could see some of them were struggling just to walk and to see," says Iqbal Qasim, one of those who helped. "Why should they not still want answers?" When a memorial service was held on the pitch later in summer, part of it was in Urdu and Punjabi in recognition.

The theatre production moved on to London last week, its players and writers wondering as they packed up what the response would be, in the capital city, to a subject even less well known and understood beyond the Yorkshire boundaries.

But they had done their job. Co-writer Matt Stevens-Woodhead had been asked to talk about the play to children at the local Parkside School a few weeks earlier – and that had been the catalyst for Hazel Greenwood to return there too. It was the place where her boys had been growing into their secondary education when the fire took them. She told the schoolchildren how she had travelled widely in the years after her husband and sons had gone, how that helped sustain her, and how they must think to travel and discover the world too.

It was on the 10th anniversary of the fire, 20 years ago, that Mrs Greenwood set up a fund, in the memory of her sons, offering the chance for young people in this place to take a journey of educational or cultural travel – as she would have wanted her own two to do. The school hall, like the theatre, was still and noiseless as the children listened to this passionate and indefatigable woman, whose family home should be full of the sound of many grandchildren, by now, but who is instead still seeking what meagre consolations she can find from the wreckage of Bradford's forgotten tragedy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks