‘He will die out there’: Severely autistic man facing deportation to Jamaica

Mother of Osime Brown says his deportation marks culmination of failings by statutory agencies over the years

When Osime Brown was issued deportation orders, the first thing he did was ask his mother whether there was a bus he could take from Jamaica to visit her in Dudley. The severely autistic 21-year-old is facing removal to a country he hasn’t set foot in since he came to the UK aged four. His mother, Joan Fairclough, is worried sick.

“If he is deported he will die,” says the former mental health nurse, 53. Seconds later she begins to cry, adding: “He wouldn’t cope. If he can’t even cope here, how is he going to cope in a environment and a culture he doesn’t know? He would be exploited because of his vulnerability.”

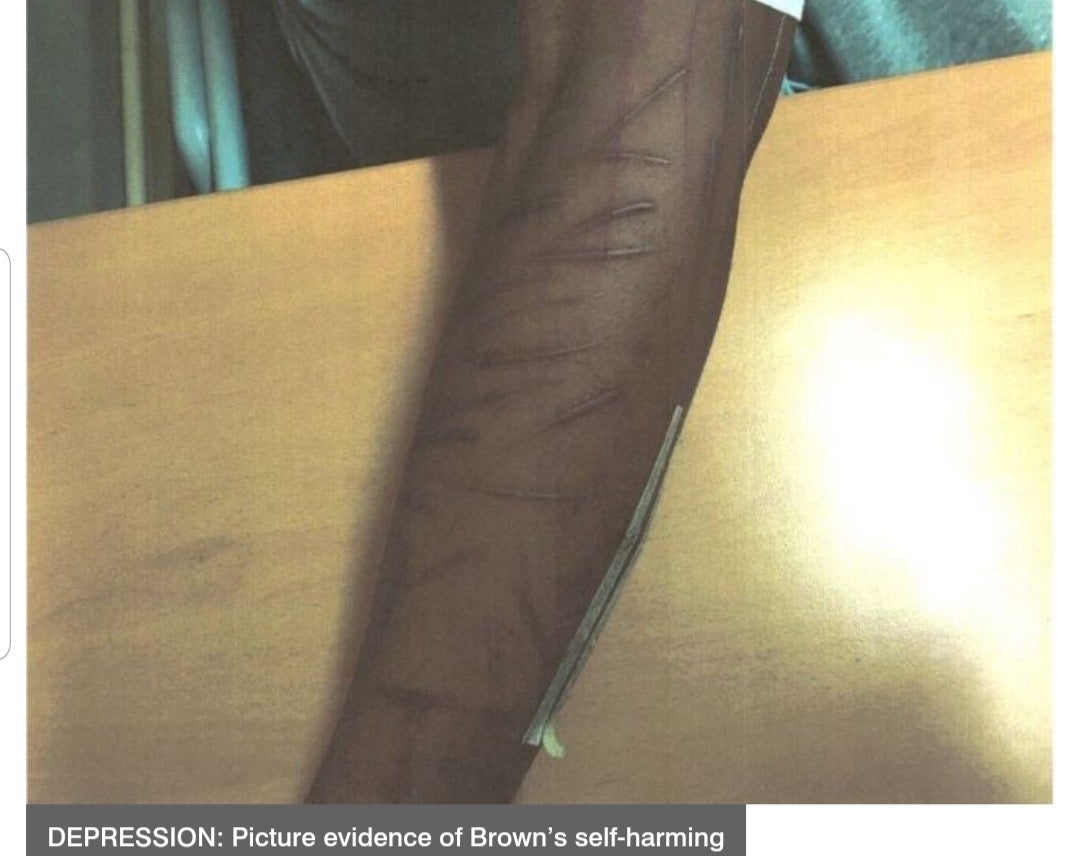

The Home Office issued Brown with a removal notice in August 2018 on the basis of a series of criminal offences he committed as a teenager, which culminated in a five-year sentence for robbery, attempted robbery and perverting the course of justice. He is currently in jail at HMP Stocken in Rutland, where he has been self-harming to the point where he has hundreds of scars on his arms and body.

His deportation was set for 3 December, until a last-minute appeal was lodged. That has since been dismissed pending a final appeal in the immigration courts which is expected to be heard this month.

The young man’s mother and siblings, along with a clinical psychologist and many who know Brown, believe his deportation marks a culmination of failings by statutory agencies over the years to acknowledge his learning disability, and subsequent failure to provide him with adequate support to cope with the challenges that come with it.

As a young child, Brown learnt to talk and walk late and developed a stutter. He received speech and language therapy at school, but he never had statutory assessment regarding his learning difficulties and special educational needs.

“They didn’t take much notice of what was behind his behaviour,” says Fairclough, talking about Brown’s experience in school. “They used to say he was disruptive and rude. They put that down to being unruly. I had to fight and fight and fight to get him assessed.”

It wasn’t until after he was permanently excluded at the age of 16, after years of struggling to interact socially at school, that his autism was diagnosed.

Shortly after this, Brown is said to have left home and moved into local authority care after telling social services that his mother was “too strict”. Fairclough says this move was taken without her permission and that it caused great distress to the family, and was ultimately detrimental to her son’s wellbeing.

“He was moved 28 times to different places within 12 months by social services. For people with autism that’s the worst thing to have happened. They like routine, which he had at home,” says Fairclough. “I went to all the social services meetings. One of the officers said this child needs to go back to his mum because he’s from a loving home, but nothing happened.”

It was while he was in the various care placements that Brown was arrested for stealing the phone from another young person along with a group of friends. The case took two years to come to trial, but he was eventually sentenced to five years in prison.

“They exploited his disability. He was an easy target to push the blame on to,” says his mother. “His autism means he always likes to please the people he’s with. He can be easily led and manipulated because he is very trusting.”

Describing the moment he was sentenced in court, Fairclough says: “He had a blank look on his face. He was looking out of space. During the court proceedings he even climbed up and pointed to himself on the monitor that was showing them walking around in the shopping centre. He did not comprehend what was happening.”

A psychological assessment of Brown by chartered psychologist John Hall, carried out in October 2019, states the way in which his life was managed when he was in care was “wholly misguided and extremely damaging”, and that had he not been placed in care he may not have found his way into a life of criminality.

“There is every reason to believe that, had [Fairclough] been listened to and instead of removing Brown from his family when he was barely 16, it would have been possible to support his mother to manage him in a situation where people loved him and who were prepared to impose a structure on his life,” states Hall.

On entering jail, the prison’s healthcare service assessed Brown and found that he was suffering from an underlying anxiety disorder and emotionally unstable personality disorder, and post-traumatic distress disorder (PTSD).

When Fairclough first went to visit her son in prison, she was surprised to see his arm in bandages. It soon transpired that he had started cutting his hands, arms and body while locked up in his cell – which his mother says she was not informed about.

“He’s not in a good state,” says Fairclough. “Last time I visited him he was crying because his tummy hurt. He laid his head in my lap and said: ‘Mummy my belly, my belly’.”

Fairclough says she is also concerned about her son’s physical health, after discovering he had fainted a number of times while in jail due to an apparent heart condition – which she believes has come about as a result of him being given large doses of antipsychotic medication in prison.

While current law stipulates that any sentence of over 12 months triggers an automatic deportation order, Brown’s lawyer, Brendan Okwor of Legacy Law Solicitors, said the young man’s case was “exceptional”.

“He came here when he was four years old, he doesn’t even know where Jamaica is. He was asking if Jamaica was in Manchester,” says Okwor. “He doesn’t know where he comes from. His family members are here. His mum, his siblings, his dad lives in America. He has no one to return to.”

The Home Office has stated in a letter to Brown that there would not be very significant obstacles to his integration in Jamaica: “You are familiar with the culture of Jamaica as you were raised by your mother/relatives in Jamaica for the first four years of your life.”

It goes on to state: “The skills and experiences you have acquired while living in the UK will assist you in your attempts to re-establish yourself in Jamaica, enabling you to financially provide for yourself and live an independent life in Jamaica.”

Hall disputes this argument, stating in his report that Brown had “failed completely” to establish himself in the UK, even with the support of social services, so being transferred to a considerably less-resourced country would “hardly be any easier for him”.

The psychologist pointed out that the mental health system in Jamaica was “grossly inadequate” and would render Brown at “serious risk” were he to be returned to that country.

He added: “In my opinion it would be an act of pure folly to do as the Home Office propose as the consequences for Brown would not only be life-changing in a very negative direction, but potentially life-threatening.”

Fairclough says that every time she mentions the deportation order during a prison visit, Brown “shuts down” and starts to rock and cover his ears.

“He doesn’t have anybody there. He hasn’t been back to Jamaica, he doesn’t know Jamaica. When he found out the Home Office wanted to remove him he said: ‘Mum, is there a bus that I can come back on?’ His removal would be a death sentence.”

If the immigration appeal fails, Fairclough hopes Brown’s criminal case can be re-opened to take account of his learning disability, describing it as a “total travesty and miscarriage of justice”.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “It would be inappropriate to comment further while legal proceedings are ongoing.”

Cllr Ruth Buttery, cabinet member for children and young people at Dudley Council, said: “We do not comment on the personal information involving individual cases, however, looked after children will always be our number one priority.”

Osime's family has set up a crowdfunder to raise funds to appeal his deportation order, which can be found here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks