The Hitler Diaries: How hoax documents became the most infamous fake news ever

Thirty-five years after forensic tests showed the diaries to have been forged, Adam Lusher recalls an extraordinary story of deception, delusion and incredulity

Sometimes you just have to shrug your shoulders, issue an apology and explain that when you try to produce news, you sometimes end up with fake news.

Shortly after the so-called Hitler Diaries were exposed as a hoax 35 years ago this Sunday, The Sunday Times, the newspaper which had believed them genuine and published extracts, excused itself with the lofty observation: “Serious journalism is a high-risk enterprise.”

The newspaper’s Australian proprietor Rupert Murdoch was slightly more down-to-earth. “We’re in the entertainment business,” he is supposed to have shrugged.

Murdoch had allegedly been equally lowbrow when, at the 11th hour, he had overridden the concerns of eminent historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, aka Lord Dacre, about the diaries’ authenticity with the immortal words: “Fuck Dacre. Publish”.

And in the innocent world of 1983, before everyone got so worried about “fake news”, it has to be said that for all but the closest participants, the Hitler Diaries affair did seem rather jolly. Even the Germans made a comedy about it, the film Schtonk!. There was also a British TV mini-series, starring Alexei Sayle as faker Konrad Kujau.

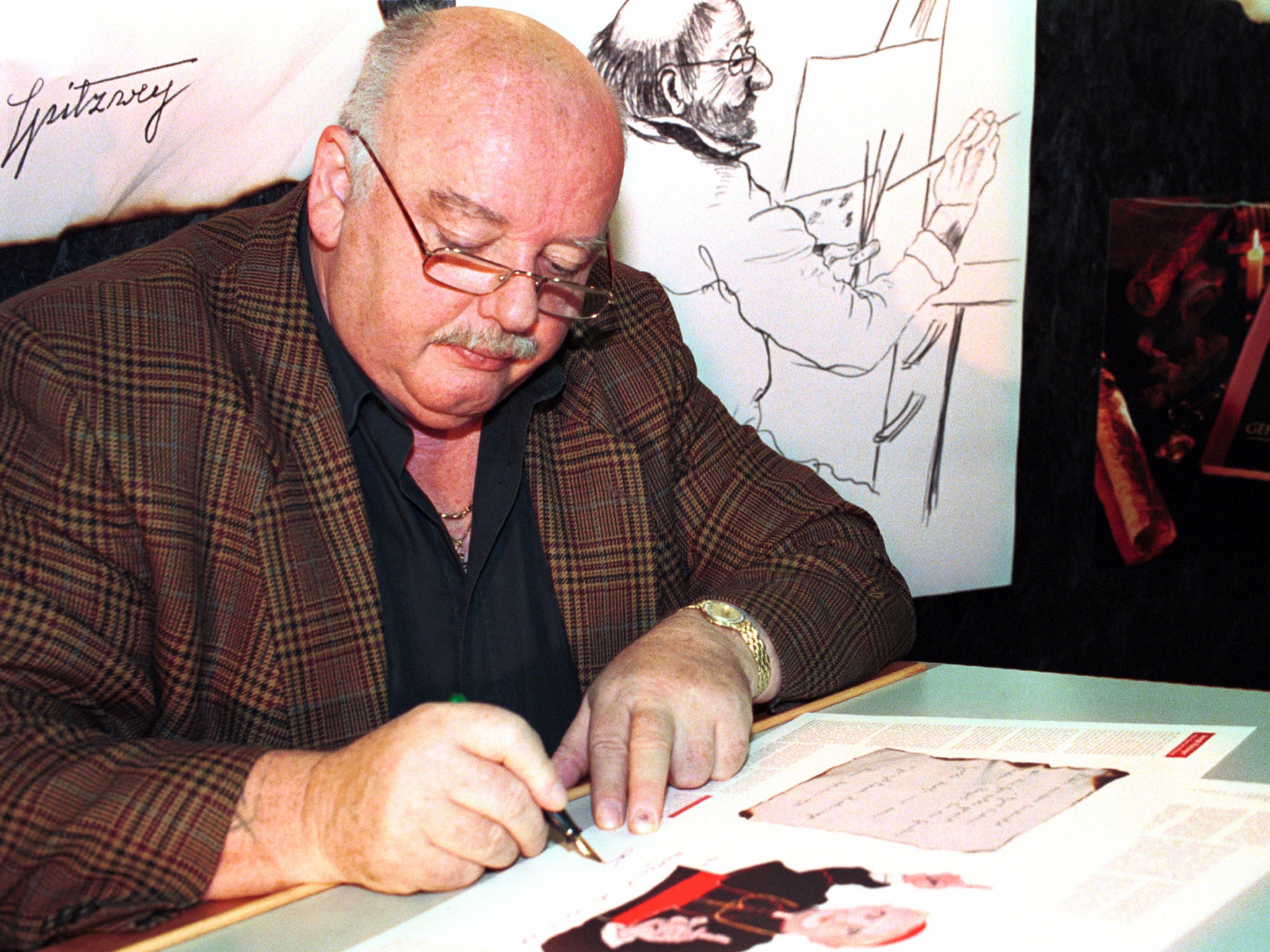

Sometimes known by the appropriate-sounding diminuitive Connie, as well as by at least eight aliases, Kujau had started his chosen career young: while in East Germany‘s Young Communist League he forged a recommendation for his own promotion. In 1957, aged 19, he found his way to the West.

As one obituary put it: “His biography is written in his police record, although there is no certainty that even this is correct.” It seems Kujau’s first conviction was for forging a small number of luncheon vouchers, but pretty soon he moved on to more substantial fare. In the 1970s, he started passing off his own paintings as those of failed artist-turned-dictator Adolf Hitler.

He even wrote authentication notes – “I painted this picture in memory of the comrades who fell in the field” – and took the trouble to pour tea over the paper to make it look old.

Kujau found forging Hitler’s paintings a profitable and relatively risk-free business. The customers didn’t want to draw attention to the fact they were collecting Nazi memorabilia, and were unlikely to seek authentication from an expert.

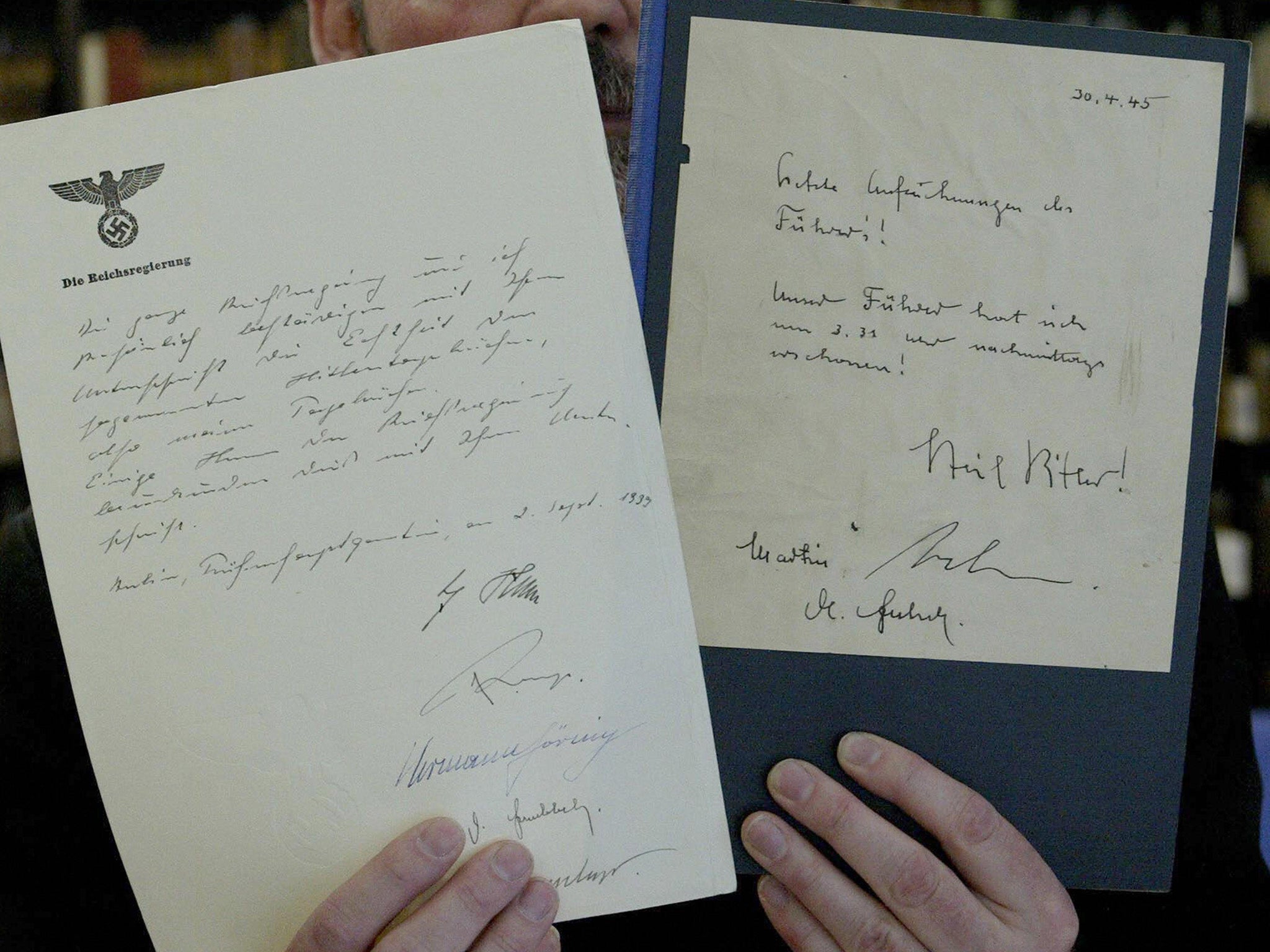

And so, Kujau seems to have wondered, why stop there? In 1978 the first Hitler Diaries were born, written on tea-aged modern paper, bound in an impressive cover with what looked like Hitler’s Gothic “AH” monogram – until you looked more closely and saw that in gluing on his cheaply acquired synthetic letters, Kujau had mistaken a Gothic F for an A, and given Adolf Hitler the initials FH. Fortunately, not many people looked closely. Until it was too late.

Kujau did do some research. He consulted an official Nazi party yearbook for 1935, and for the tricky 1945 bunker period he relied on an account of the last days of the Second World War published by Bild. “As Hitler, I had to know exactly what was happening,” he proudly explained to the subsequent trial.

But at times he ran out of inspiration. Which explains why in one entry the all-powerful Fuhrer supposedly confided to his diary: “Have to go to the post office, to send a few telegrams.”

But Kujau still managed to sell his first “diary” to a collector of Nazi memorabilia. And by the end of 1979 word had slowly filtered through to journalist Gerd Heidemann of Germany’s Stern magazine.

To his colleagues and rivals, Heidemann was a “bloodhound reporter”. Perhaps a little overinterested in the Nazi era – he had embarked on affair with with Hermann Göring’s daughter after being sent on assignment to buy the old Luftwaffe boss’s yacht – but a scoop machine nonetheless.

And so began a merry dance between the forger and the journalist, involving lengthy negotiations and large sums of money. Precisely what passed between the two remains contested.

When it came to court, Kujau, charged with receiving $549,000 from Heidemann, claimed the journalist was a partner in the scam and milking Stern for money.

Heidemann’s version was summed up in two statements. ‘’I have never known a person who lies so much,” he told his trial, indicating his co-defendant.

Years after he was given a four-year prison sentence, Heidemann complained bitterly about his former journalistic colleagues. “I was the big scapegoat for them,” he said. “They all ganged up on me. There was a lot of envy and schadenfreude involved.”

He has always insisted he was another innocent victim, fooled by Kujau like everyone else was.

But however it was achieved, Stern offered nearly nine million marks (around £2.35m in the early 1980s) for the diaries. There were now 61 volumes covering everything from 1932 to 1945, because Kujau had been working hard with the writing, the tea-staining and the consulting of Nazi yearbooks.

The explanation for how the diaries were discovered was relatively simple, but suitably romantic and mysterious.

In April 1945, it was said, a plane carrying some of Hitler’s belongings had crashed near Dresden.

Humble local farmers were then supposed to have hidden the diaries in a hayloft. Then a mysterious high-ranking East German army officer had got hold of them.

Now, it was claimed, he wanted to sell. Stern bought, and The Sunday Times gave Stern a down payment of $200,000 to secure British and Commonwealth publication rights.

But of course the newspaper wanted to do its own checks on the authenticity of the diaries.

And for this, The Sunday Times turned to one of the greatest historians of his generation: Professor Hugh Trevor-Roper, author of The Last Days of Hitler, and Hitler’s Table Talk, now elevated to the title of Lord Dacre of Glanton.

At first, Trevor-Roper declared the diaries “an archive of great historical importance”. Then he thought a little harder.

But on the morning of Saturday 23 April 1983, The Sunday Times’ sister paper The Times had run an article quoting Trevor-Roper as a teaser for the first instalment of the Hitler Diaries.

By that evening more than a million copies of The Sunday Times, with an eight-column “world exclusive” featuring the headline “Hitler’s Secret Diaries” in letters two inches high, were starting to come off the presses.

The editor Frank Giles was enjoying a celebratory drink in the office with senior colleagues. They decided to call Trevor-Roper to share their delight and to sound him out about the possibility of him doing a follow-up for next week’s paper.

What happened next has passed into Fleet Street legend. In his 1986 book Selling Hitler, the author Robert Harris described what the other newspaper executives heard of Giles’ side of the conversation.

“Well, naturally, Hugh, one has doubts. There are no certainties in this life. But these doubts aren’t strong enough to make you do a complete 180-degree turn on that? Oh. I see. You are doing a 180-degree turn...”

Senior news executives like this do not get to the top of their profession for nothing. It is said that they first decided to get Trevor-Roper to keep quiet about his doubts so that next weekend they could have another world exclusive: “Top Historian Says Hitler Diaries Fake”.

Then they phoned Murdoch. The boss said: “Fuck Dacre.” The presses kept rolling. And on 24 April The Sunday Times sold like hot cakes.

Unfortunately, however, Monday 25 April did not go as well. Stern called a press conference in Hamburg to trumpet their publication. Trevor-Roper was there. He did not keep quiet about his doubts.

“I regret that the normal method of historical verification has been sacrificed to the perhaps necessary requirements of a journalistic scoop,” he said.

The future Holocaust denier David Irving was there too. He demanded to know how Hitler could have written the entries immediately following the 20 July 1944 bomb plot, given that he had been wounded in the arm.

He further denounced the diaries as forgeries. He got no answer when he demanded to know whether the ink in the diaries had been tested.

He had to be forcibly ejected by security, yelling “Ink! Ink!” as he was dragged out. The rest of the press pack turned their attention from the worthies of Stern to Irving, and some threw punches in their determination to get the best view of the ejection.

To cap it all, German chancellor Helmut Kohl was by now also expressing doubts about the authenticity of the diaries.

Further forensic tests were ordered, and on 6 May the results were in. The ink was of modern, not wartime vintage. Measurements of how much chloride in the ink had evaporated proved that the tested volumes had been written in the previous two years.

The German government was informed, and made an official announcement.

Kujau fled with his wife and mistress to Austria, telling his wife that his mistress was his cleaner. After he returned to hand himself in, he made a confession that accused Heidemann of complicity.

But their trial was far from just a tedious slanging match between Heidemann and Kujau about who knew what. There was, for example, the moment when the prosecution showed the jury photos of Heidemann’s beautiful Hamburg apartment.

The prosecutor had no problem pointing out to the jury the Nazi-era beer mugs, military hats, and swastika banner that was supposed to have adorned Hitler’s opera box. But he had trouble identifying a rather voluminous item of clothing.

What is that, he demanded of the defendant Heidemann. “Those are Idi Amin’s underpants,’’ replied Heidemann. ’“I hung them up there for laughs.’’

No one disputed the authenticity of the former Uganda dictator’s Y-fronts, but The New York Times did observe: “The Hitler Diaries trial has turned into an amusing drama about greed and gullibility.”

But four editors in three countries effectively lost their jobs to the Hitler Diaries affair. Frank Giles stepped down from The Sunday Times editor’s chair.

In 1985 Heidemann and Kujau were both sentenced to four years and eight months in jail. When Kujau was released after three years, he became a celebrity. He opened a gallery of forgeries in Stuttgart, although he did get fined £2,000 for doing a little driving licence counterfeiting on the side.

When he relocated to Majorca, German tourists would seek him out to ask for demonstrations of the art of forgery. He died in 2000, although The Guardian‘s obituary did warn that “he might still be around somewhere, having pulled off his last grand sting”.

Heidemann fared less well. In 2008 reporters found him aged 76, living alone in a cramped Hamburg apartment on £280 a month, and still bitter about the way he had been treated.

The historian Trevor-Roper was also left badly damaged. For all his glorious academic achievements, it was the Hitler Diaries for which he was remembered. When he died in 2003, the headline on The Independent’s obituary called him “The Hitler Diaries historian”.

Rupert Murdoch, though, is still in “the entertainment business”. In respect of the Hitler Diaries, he has also been credited with the blithe statement: “Circulation went up and it stayed up. We didn’t lose money or anything like that.”

Robert Harris later wrote that the statement itself was accurate, even if Murdoch might not have been the one who made it. Harris wrote that Stern returned to News International all the money it had paid for the British rights, and The Sunday Times retained 20,000 of the 60,000 new readers it acquired when it published its “scoop”.

Mr Murdoch lost an editor, but in monetary terms, that particular bit of fake news cost the billionaire nothing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments