Korchnoi remains defiant, but a new foe looms

He has glowered across a chessboard at the savants of six different generations. In 1953 he played a grandmaster, Grigory Levenfish, who was born in 1889; more recent opponents include the current world No 1, Magnus Carlsen, born in 1990.

At 78, however, Viktor Korchnoi remains revered not just for past endeavours – which qualify him as one of the authentic chess giants – but also for his ageless appetite. In a game that nowadays identifies its prodigies earlier than ever, his must now be considered a more truly freakish genius. The old grandmaster’s horror of defeat remains undiminished, exactly half a century after his first international tournament success.

Korchnoi has been spending the past few days in London, as guest of honour at the London Chess Classic. He remains as spry and engaged as ever and – to any who remember only the cantankerous, suspicious demeanour of the years after his defection from the Soviet Union in 1976 – full of surprising warmth. But mellowness is a relative concept in a man who cherishes a withering revulsion for any upstart with the temerity to beat him.

“Sometimes I felt I had to stop,” he admits. “They say: ‘You have done so much in this life. You can relax.’ Then I play a game, and I lose to somebody. And I look at him. I look at who he is, as a chess player. And I look at who he is, in general. And when I do this, I know why I will never stop.”

He gives a deep, satisfied chuckle. Dapper, measured in speech and movement, Korchnoi registers the cadence of his conversation with heavy hands and eyelids. Here is the man who would be nobody’s pawn.

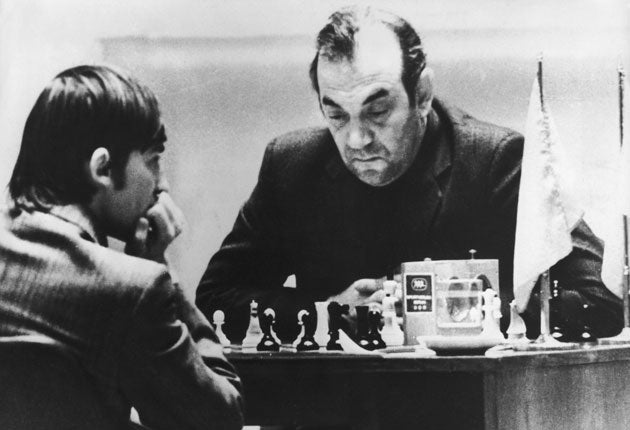

In his time, Korchnoi was a central character in the epic, deranged saga of East-West chess showdowns that engrossed millions around the world. The chessboard became no less a motif of the Cold War than Checkpoint Charlie. Korchnoi’s defection in Amsterdam saturated his world championship duels with Anatoly Karpov, the darling of the Soviet establishment, with political symbolism. It was also the era of the American maverick Bobby Fischer, and the Soviets were desperate to depict the West as intellectually bankrupt in a series of showdowns: first between Boris Spassky and Fischer, then between Karpov and this reviled apostate, Korchnoi. Incongruously, the most sedentary of pursuits had suddenly become the stuff of melodrama.

His first match with Karpov, in the Philippines, became an epic of paranoia and controversy. Korchnoi’s camp protested against the arrival of blueberry yoghurt for his opponent as a coded message; in his autobiography, Korchnoi instead concludes that Karpov was being drugged. He also felt that he was being targeted by a Soviet parapsychologist, gazing from the gallery; in turn Korchnoi summoned transcendental forces of his own, enlisting the help of yogis.

Fischer, who died last year, infamously lost all connection with the world after beating Spassky. But Korchnoi has never faded, in any sense. In a recent tournament he was asked how he proposed to beat a younger opponent. “I shall tire him out,” he said. And so he did, closing out the match by winning the last three games.

It is not difficult to trace the roots of this voracious hunger. As a boy, Korchnoi lost his father in the war, and then had to survive the grotesque privations of the Siege of Leningrad. “A youngster can live anywhere because it’s his life, he has not seen anything else,” he says. “But it did get into my blood that I have to be alert, have to fight – whether against difficult conditions in life, or against authority. From the very beginning, I was forced to become a fighter. A fighter in life, and so a fighter in chess.”

This refusal ever to submit meekly did not endear him to the Soviet authorities, who soon identified the emerging Karpov as their poster boy instead. Karpov was everything Korchnoi was not. He belonged to the working class, not the intelligentsia; he was a conformist; and he had no Jewish blood.

“In 1999, a former KGB worker came to live in England,” he says now. “He [wrote] that in order to ensure victory for Karpov, 17 KGB [agents] had been sent to the Philippines. Everything was clear. If I were to beat Karpov, I would be exterminated. It would have been the Marcos people who would have done it. We all felt it, in our skin.”

So he truly thought himself in mortal peril, yet fought to beat Karpov as though his life depended on it? “We have to believe in the presence of a higher being,” he says, shrugging expressively. “It was not deliberate that I lost the match.”

The ultimate irony is that the Soviet machine, in identifying chess as a political vehicle, arguably hastened its own breakdown. For Korchnoi acknowledges that this game of set patterns, confined by 64 squares, contains within it so many different possibilities that it emboldens the instincts of liberation. “The Soviets had forgotten that the game is played by an individual, who is fighting for himself,” he says. “And so it happened that, one after the other, strong, independent-thinking grandmasters appeared, and caused difficulties for the regime. When I defected it was because of chess, not politics. I wanted to be a free person. Freedom is my essential stance.”

Chess players, of course, are either tremendously clever – or plain crazy. Korchnoi invokes the Austrian novelist, Stefan Zweig, who held that the game is mastered either by the mind that can only flourish within the confines of the board – or by the genius that could prosper equally in any other field. He does not consider himself one, but he has encountered them. “And someone like this could be a writer, a composer, an actor, could bring fantastic benefits to mankind,” he says, before giving that delightful bark of laughter. “Then some fool teaches him to play chess!”

It is at this nexus between programming and intuition that Korchnoi contemplates the increasing sophistication of computer chess. Is there some kernel, beyond the reach of computers, where the human mind can only get something right because it also gets things wrong?

“I hope so,” he says. “But I am very pessimistic. I am afraid that in 100 years human chess may disappear. Only the mechanical chess will be there. That is my fear. When a computer produces everything it can be made to know, it can look like intuition. And the computer has no ego, no fear, never gets tired.”

But surely a man like Korchnoi can only discover the infinite possibilities of the 64 squares because of his uniquely quixotic, maddening, inspired spirit? Here, after all, is a man who extends his career to a seventh generation if you include Geza Maroczy, the Hungarian grandmaster who lived from 1870 to 1951. Korchnoi “beat” him, through a medium, in 1985.

“You can play a position slowly, without risk,” he muses. “Maybe you win, maybe not. But when you take risks, you check character. Some players are full of fantasy and fighting spirit. Others just imitate computers. They like to call me Viktor the Terrible. It’s true I don’t like chess players who are trying to catch fish – just sitting by the water for hours, hoping to catch something. I do prefer fighting people. I believe the two players should not be friendly to each other. Sometimes when I don’t have respect, it is dangerous. Many times have I lost silly games like this. But I learned to fight at the chessboard. And I am still fighting.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks