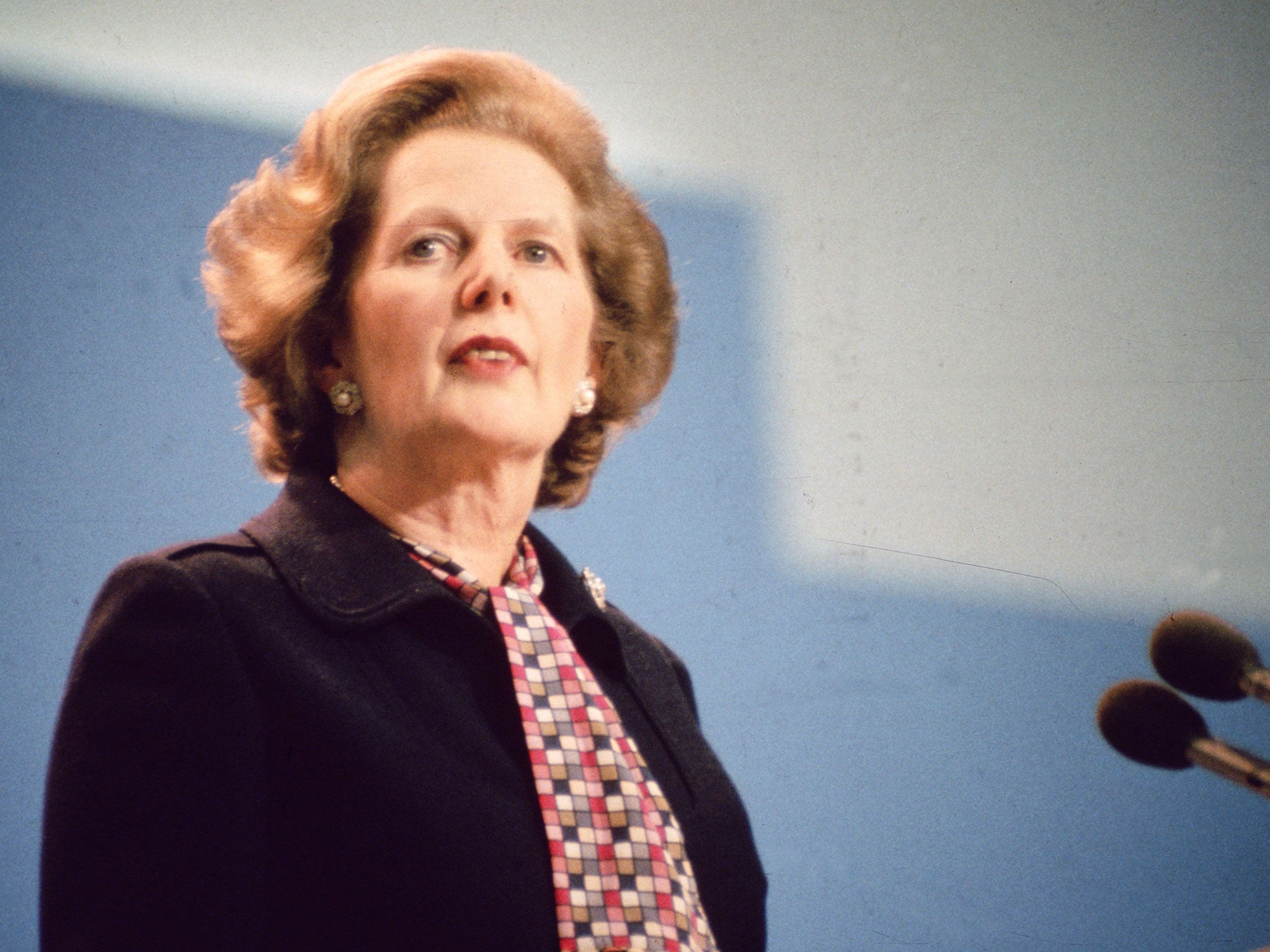

National Archives release: Margaret Thatcher nearly sent in the Army to crush miners, secret papers reveal

Files released under the 30-year rule reveal how the Thatcher government tried to stifle the National Union of Mineworkers’s funding from the Soviets

Union leaders suspected of smuggling “suitcases full of banknotes” from Moscow into Britain during the miners’ strike were placed under surveillance by MI5 as part of a plan hatched by Margaret Thatcher’s government to end the industrial unrest, according to secret papers.

Senior aides to Mrs Thatcher were so desperate to choke off the flow of money from the Soviet Union to the National Union of Mineworkers led by Arthur Scargill that they considered using MI5 to tip off Customs officers to search officials believed to be bringing cash into Britain after collecting it from Swiss bank accounts.

A “secret and personal” memo sent to Mrs Thatcher by Cabinet Secretary Sir Robert Armstrong at the height of the strike in 1984 suggests the discovery of the money “might well leak” and damage the reputation of the NUM or the consignments could be seized to pay a £200,000 fine outstanding against the union and Mr Scargill.

The close involvement on the Security Service in operations against the NUM is one of several files released under the 30-year rule by the National Archives in Kew, west London, which cast new light on the tactics deployed or contemplated by Mrs Thatcher’s government as it fought the defining industrial conflict in one of the most fraught years of her premiership.

A separate document reveals that the prime minister, who survived the Brighton bomb in the same year, secretly considered calling out troops and declaring a state of emergency amid mounting concerns that her government was facing defeat in the epic 12-month strike over plans to close 20 loss-making pits which sparked brutal picket line clashes such as the infamous “Battle of Orgreave”.

More freshly released information from the National archives:

Plans were drawn up in July 1984 for thousands of military personnel to be mobilised to commandeer trucks and move vital supplies of coal and food around the country after the outbreak of a docks strike while miners were still out.

Amid a warning from former Cabinet minister John Redwood, then the hawkish head of the Downing Street policy unit, that a victory for the unions would be “the end of effective government in Britain”, the papers reveal how Mrs Thatcher’s closest aides sought to counter what many in her circle considered to be little short of a left wing insurgency.

After being alerted by MI5 to the shipments via Switzerland of suspected Soviet cash to the NUM, Sir Robert warned Mrs Thatcher in November 1984 that there was nothing that could be done legally to prevent the money entering Britain.

The existence of a financial lifeline to the NUM in the closing months of the strike was acknowledged within the Soviet Union after the TASS news agency reported that £500,000 had been donated by Russian miners to their British brethren.

But in London there was no doubt that the funds came with Moscow’s approval and may indeed have come directly from the Kremlin’s coffers.

While noting that there were no powers to stop the money being brought into Britain, Sir Robert, who as Cabinet Secretary was Britain’s most senior civil servant, indicated there would be methods of making life difficult for the NUM.

He wrote: “If a representative of the NUM could be detected entering this country with a suitcase full of bank notes, it might be possible for him to be stopped and searched by Customs.”

With more than a hint of tongue in cheek, he added: “Such a discovery might well leak: the Customs can be a deplorably leaky organisation, and so can the police.”

The memo made it clear that MI5 was watching NUM staff to see if they travelled to “foreign destinations” to pick up cash consignments, adding that any attempt by the union to process the money through its bank accounts could be “discreetly” reported to the official in charge of enforcing the £200,000 fine against the NUM for contempt of court.

Sir Robert also hints at behind-the-scenes briefings to sympathetic journalists to ensure that Mr Scargill was asked uncomfortable questions about the cash.

He added: “I am afraid that this is not certain to yield results, but I am satisfied that it is the best we can do.”

A reply to the document from Robin Butler, Mrs Thatcher’s private secretary, makes it clear that she was fully aware of the cloak and dagger operation. Mr Butler replied: “The Prime Minister has read and noted your minute.”

Whether the proposed interception of cash-mule NUM officials ever took place goes unrecorded. But MI5 has previously acknowledged that it conducted surveillance of Mr Scargill, monitoring contacts between him and the Communist Party of Great Britain. On its website, the Security Service insists that it was “less fearful of subversion than the Prime Minister”.

Such concern that the strike was merely the backdrop to a wider ideological struggle (Mr Scargill described the strike as a “social and industrial Battle of Britain”) is revealed to have pervaded the government’s response to the strike.

In his memo to Mrs Thatcher, Mr Redwood said the purpose of Britain’s left wing was to “oppose and destroy” while officials drew up contingency plans to conserve coal stocks, including the possible imposition of a three-day week. In one briefing, Norman Tebbit, then trade and industry secretary, warned that coal stocks were beginning to run perilously low.

In the end, however, the government emerged victorious. The national docks strike soon petered out and by late November significant numbers of miners were returning to work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments