National archives: Shock at scale of Maze jailbreak, the laser weapon deployed to Falklands and other revelations

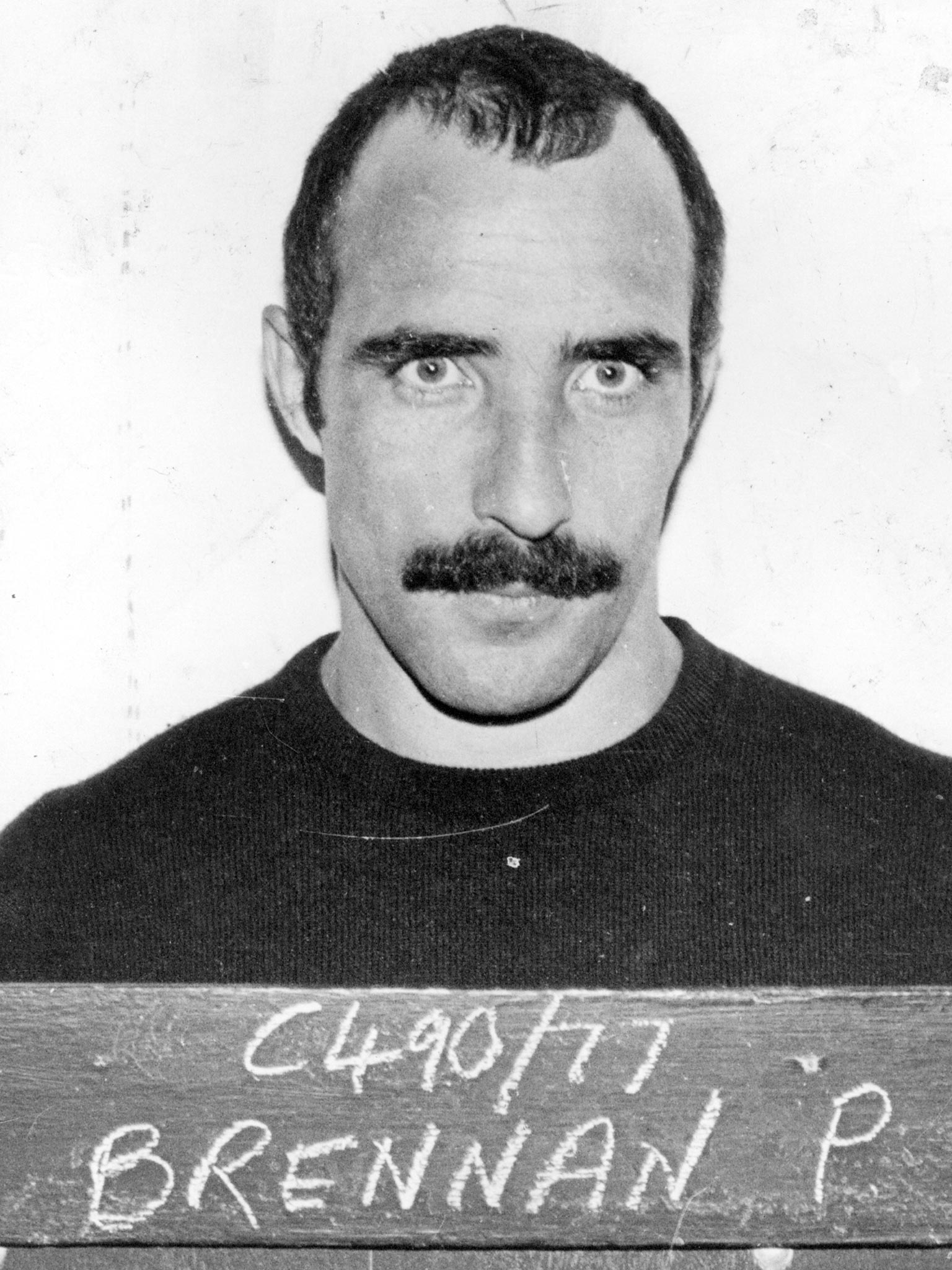

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared it was “even worse than we thought” after learning the details behind the top-security Maze prison breakout in which 38 IRA inmates went on the run on 25 September 1983. The mass escape from the Northern Ireland jail became the worst prison breakout in British history.

The Northern Ireland Office report details how the escape from the H-Block unfolded. Strongly worded advice sent from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to its mission read: “You should take every opportunity to limit the propaganda benefit the IRA will reap from the outbreak.”

One prison officer was killed and another seriously injured. The prisoners used smuggled guns and knives to overpower staff before hijacking a food lorry. Security forces mounted the biggest search operation Northern Ireland has ever seen within minutes of the escape from the prison near Lisburn. Ten prisoners were recaptured within the first few hours.

Northern Ireland Secretary James Prior had asked the Chief Inspector of Prisons Sir James Hennessy to carry out an inquiry. “It will be prompt, rigorous and searching,” the document states. “You should restrict comment to the above while not commenting on the details of the outbreak or on speculation about lax security.”

Prison officers were “overpowered” in a series of attacks at 2.45pm. A prison officer who was on duty in the H7 control room was shot twice in the head by a prisoner firing through the grille.

The document states: “The prison officer driver drove the van out of H7 with 37 prisoners concealed in the back and one prisoner kneeling on the floor of the cab with a gun pointed at the prison officer’s stomach. The van passed through two manned control gates without being searched despite the standard security rule at Maze that all vehicles are checked when passing through a control gate.”

Plan to break miners strike by force

Margaret Thatcher secretly considered using troops to break a strike by coal miners, according to newly released government papers. The Kew papers show the extent of the planning by Mrs Thatcher’s Conservative government for the decisive showdown with the miners which helped define her political legacy.

They reveal that ministers and officials repeatedly warned that a confrontation with the National Union of Mineworkers and its left-wing leader, Arthur Scargill, was inevitable.

Mrs Thatcher, who had been a minister in Edward Heath’s government in the 1970s when it was brought to its knees by a miners’ strike was well aware of the stakes.

In February 1981 – less than two years into her premiership – she had been forced to cave in to the NUM’s pay demands, aware that the Government was unprepared to withstand a prolonged conflict.

Behind the scenes, however, a secret Whitehall working group – codenamed MISC 57 – was established to lay the ground for the battle to come.

They began to buy land next to electricity power stations – which were nearly all coal-fired – so coal could be stockpiled to keep them running through a strike. They also started converting stations to dual-firing so they could run on oil if coal supplies were exhausted.

MISC 57 discussed using troops to move coal, although officials warned it would be a “formidable undertaking”.

In a memorandum dated October 27 1983, PL Gregson at the Cabinet Office noted: “A major risk might be that power station workers would refuse to handle coal brought in by servicemen in this way.”

The next day, however, a meeting of senior ministers chaired by Mrs Thatcher ruled that while they might be able to rely on existing coal stocks in the early stages of a strike, planning for the use of troops should continue.

“It was agreed that... it might be necessary at some stage to examine more radical options for extending endurance, including the use of servicemen to move pithead stocks to power stations,” the minutes noted.

As the Government moved towards the general election of 1983, preparations for an expected conflict over pit closures was stepped up.

In January 1983, Energy Secretary Nigel Lawson said while the National Coal Board (NCB) was still not yet confident of winning a strike, they needed to be ready for a decisive showdown once the election was out of the way.

“While the board are currently thinking a national strike would last for two months, I believe it could well be longer,” he wrote to Mrs Thatcher.

“If Scargill succeeds in bringing about such a strike we must do everything in our power to defeat him, including ensuring that the strike results in widespread closures.”

Invasion that tested the special relationship

It was the moment the fabled partnership between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan almost hit the rocks.

The US invasion of Grenada in 1983 came as a bitter shock to the Prime Minister, who was appalled at the military intervention in a Commonwealth state. .

The crisis erupted when what Reagan referred to as “leftist thugs” assassinated elected prime minister, Maurice Bishop and seized control.

At 7.15pm on October 24, Downing Street received a cable from Reagan saying he was giving “serious consideration” to an Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States request to intervene and asking for Thatcher’s “thoughts and advice”. She was composing a reply when, at 11pm, a second telegram appeared saying the President had decided to “respond positively”. Alarmed, she summoned Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe and Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine for consultations before expressing her “gravest concern”. Her telegram said: “This action will be seen as intervention by a western democratic country in the internal affairs of a small independent nation... I cannot conceal that I am deeply disturbed by your latest communication. You asked for my advice. I have set it out and hope that even at this late stage you will take it into account.”

She then made a brief call at 12.15am on a secure line urging Reagan to consider her telegram “very carefully indeed”. As news filtered through of the landings, Reagan sent a further telegram explaining a delegation from Cuba had been seen on the island.

Thatcher’s embarrassment was compounded as only the day before Sir Geoffrey had told the Commons the Government had no reason to think US intervention was likely.

That evening the President rang her to try to patch up their differences. He “very much regretted the embarrassment” but explained he had been forced to move quickly for fear news of the invasion would leak.

Mrs Thatcher appeared to have received his explanation with icy disdain, barely speaking during the 15-minute conversation.

The row cast something of a pall over their close relationship. Nevertheless, files suggest she still had the President’s ear at times of crisis. The day before the Grenada invasion, almost 300 US and French personnel were killed by suicide truck bombers in Lebanon.

The next month Thatcher was able to dissuade Reagan from “retaliatory action”. She wrote: “In such circumstances leaders find themselves in a lonely position and I want to let you have my frank views as someone who has been in a similar situation.”

‘Greenham women? They are all eccentric’

Margaret Thatcher dismissed the Greenham Common peace women as an “eccentricity”.

The women’s peace camp, which was set up outside the Berkshire air base following the decision to deploy US nuclear cruise missiles there, became an abiding feature of the 1980s.

But the Prime Minister was adamant she would not be deterred by their activities.

A No 10 note of a meeting with US Vice President George Bush Sr in June 1983, five months before the first missiles arrived, reported: “The Prime Minister said they had become an eccentricity. Their activities had been inflamed by the media. They were very unpopular in the area of Greenham Common because of the disruption caused to normal life.

“She had no doubt that when the time came to deploy cruise there would be further problems but these would have to be surmounted.”

Bring me back a fertile panda

A plea for a fertile female giant panda plus crib notes titled “A Hasty Guide To The History of China” were part of Margaret Thatcher’s preparations to visit China in 1982.

Cabinet Secretary Robert Armstrong jotted down a reminder that London Zoo would quite like to get a fertile female giant panda from her trip in September 1982.

He recalled that a pair of giant pandas had been presented to former Prime Minister Edward Heath during his visit eight years earlier. “Unfortunately, the female is highly unlikely ever to breed” but the male has “proved his fertility”, he noted.

“London Zoo would clearly like to have a fertile female and, in due course, a baby panda.”

To help her brush up on her Chinese knowledge there was a guide which provided a briefing of the country dating from “pre-history”, through the nation’s various dynasties. Official briefing notes, issued ahead of her talks with the Chinese government, show the Conservative leader was warned that politician Deng Xiaoping would be “older and deafer, though still alert”.

It is also noted that premier Zhao Ziyang had “gained in stature and confidence”.

The file covers Mrs Thatcher’s meeting with Deng and Zhao on the future of Hong Kong.

This was a “sensitive and immediate” situation needing official talks to reach an agreement on arrangements for the administration and control after 1997.

On a personal note, Britain’s only female head of government had wanted a thankyou letter to be sent to an embassy worker who had stopped her from having a bad hair day.

Among the letters of thanks, detailed in a 24 September 1982 letter from Downing Street, was a note stating: “A person in the embassy who made a special contribution to the visit is Miss Elaine Robertson, who kindly lent her Carmen rollers to Mrs Thatcher.”

Laser weapon deployed to Falklands

Britain deployed a laser weapon to the Falklands which was designed to “dazzle” Argentine pilots during battle – but despite being hurriedly and quietly developed, the weapon was never used in action.

Its existence is disclosed in a January 1983 letter, marked “Top Secret and UK Eyes A”, from the then newly appointed Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine to the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher.

Mr Heseltine wrote: “We developed and deployed with very great urgency a naval laser weapon, designed to dazzle low-flying Argentine pilots attacking ships, to the task force in the South Atlantic. This weapon was not used in action and knowledge of it has been kept to a very restricted level.”

His briefing on military capabilities also touches on the laser weapon research and development programmes called Raker and Shingle which were “proceeding at high priority”, according to the papers.

He claims the Soviet Union could field laser weapons by the mid-1980s but it was uncertain whether owning such offensive laser weapons was useful. By the end of 1979 British interests lay in using medium-power lasers directed against relatively softer targets such as eyes, optic and electro-optic sensors.

Mr Heseltine’s note claims “the Russians could be in a position to field such weapons by the mid-1980s (in fact, the Russians may already have deployed a laser weapon on the cruiser Kirov)”.

Labour unilateralism worried Whitehall

Officials feared the election of a Labour government committed to unilateral nuclear disarmament could wreck Britain’s alliance with the United States.

Labour leader Michael Foot fought the 1983 general election on a unilateralist manifesto – dubbed “the longest suicide note in history”. Civil servants working behind the scenes were desperate to steer an incoming Labour administration away from a clash with Britain’s major allies.

The Cabinet Secretary Sir Robert Armstrong drew up a list of issues for the new prime minister which would have to be addressed as a matter of urgency. “The most pressing are in the nuclear field where manifesto commitments to halt cruise missile deployment, cancel the Trident programme and include the British Polaris force in the current nuclear disarmament negotiations impinge directly on the interests of the United States and of Britain’s other Nato allies,” he wrote.

“You will wish to look for early advice from the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary and the Defence Secretary on how best to handle these issues so as to avoid or minimise damage to the cohesion of Nato.”

The Ministry of Defence was even blunter when it came to the prospect of Labour ending the presence of US military forces in the UK. “The jettisoning of an alliance commitment by a major European ally could give added impetus to the isolationist movement in the US and begin a process of decoupling US forces from the defence of Europe,” one official wrote.

The briefings were not needed. Labour was trounced, as Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives were returned to power in a landslide with a 144-seat majority.

PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments