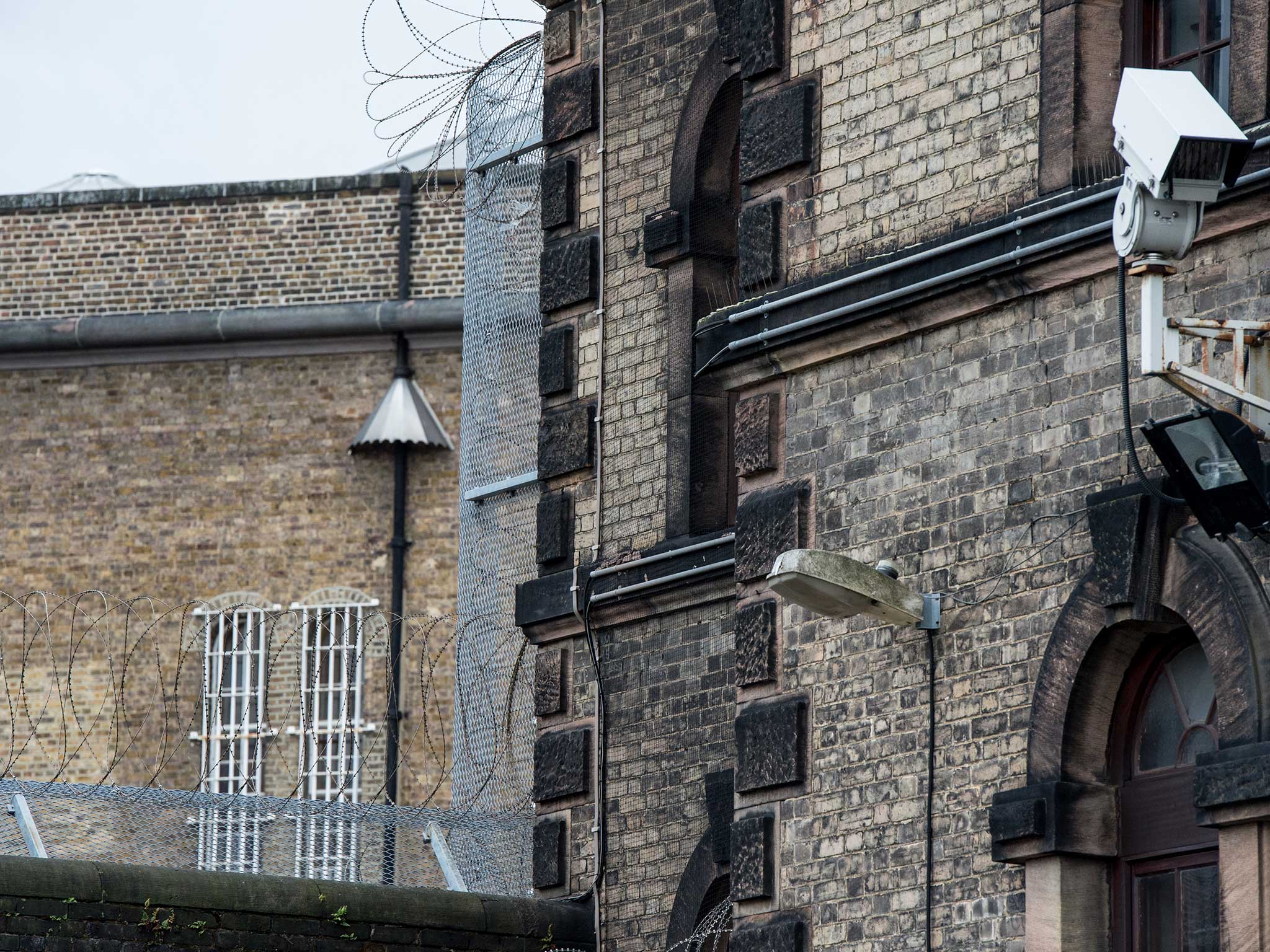

Government's privatisation of probation services 'putting public at risk' as offenders monitored by phone

Convicts committing murder and rape while under supervision in ‘two-tier’ system

The public is being put at risk by the Government’s failing privatisation of probation services as criminals commit murder and sexual offences while supposedly under supervision, a damning report has found.

HM Inspectorate of Probation said private companies commissioned in a 2014 overhaul of the service were failing to properly assess the risk of harm in half of cases, supervising thousands of convicts with phone calls every six weeks.

Some junior officers working for Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) are handling more than 200 cases each, despite officials warning that a maximum of 60 can be taken on safely.

HM Chief Inspector of Probation, Dame Glenys Stacey, questioned whether the current “two-tier” system could ever deliver the public protection and rehabilitation needed.

“If these services are delivered well, there will be fewer children in care, fewer adults and children living in fear of assault, fewer people sleeping on the streets and fewer people in prison,” she told a briefing in London.

“These services aren’t very visible but they really do matter…neglected prisoners are more likely to reoffend.”

In a damning assessment of the picture across England and Wales, Dame Glenys said the Government’s Transforming Rehabilitation programme had overestimated revenue for private companies taking on parts of the probation service, forcing them to make cuts to staff and services.

Probation trusts were replaced by the new National Probation Service (NPS) and 21 CRCs, owned by eight separate organisations with different constitutions.

They were intended to handle only low-risk offenders, alongside a programme preparing prisoners for release and community service, but are now handling a large number of “medium” risk convicts.

“Individuals assessed originally as presenting a medium or low risk to the public can go on to commit very serious further offences,” the report warned.

It found the NPS was protecting the public well but the work of CRCs was unsatisfactory in half of cases.

Since the reforms in 2014, the number of convicts committing a serious further offence while under probation supervision has risen by 20 per cent, from 429 to 517.

A significant proportion are convicted of murder, manslaughter or sexual offences, the report found.

Some convicts may only undergo one face-to-face meeting with CRCs before being assigned a risk category and pushed into “remote offender monitoring” by telephone.

Dame Glenys admitted there was no way of ensuring probation officers were speaking to the person they had been assigned, adding: “The risks are apparent.”

“I find it inexplicable that, under the banner of innovation, these developments were allowed,” the inspector continued.

“We should all be concerned, given the rehabilitation opportunities missed and the risks to the public.”

She said the inspectorate had uncovered a number of cases where “unsuitable” candidates were being supervised by phone – a method used for 40 per cent of people on probation under some CRCs.

In one case, a Class A drug dealer attacked a man with a crowbar while under telephone supervision.

Another convict was assessed as low-risk after a short prison sentence for driving while disqualified, despite having more than 30 previous convictions including domestic abuse and violent assaults.

The alarm was not raised when he moved back in with a former partner who he had abused – even after eight police call-outs – and contact was lost until he was charged with another attack on his partner.

The inspectorate concluded that rehabilitation efforts were failing in more than half of both CRC and NPS cases, seeing prisoners released without homes, jobs, rehabilitation programmes or education opportunities.

More than 260,000 people were under probation supervision last year, including 40,000 who served sentences under 12 months.

Many are handed community or suspended sentences, including unpaid work (60,000 cases a year) or Rehabilitation Activity Requirements (75,000 cases a year).

Dame Glenys said the programmes aim to “change people’s approach to life but the freedoms introduced are not being used in the manner intended”.

She said some people were being “stood up” by CRCs after attending at agreed times to carry out work, while companies were counting short meetings as a day of activity under a loophole in contracts.

The inspectorate found the agreements and resulting financial pressures to be the cause of most failures, alongside delayed IT system updates by the Ministry of Justice.

“The Government’s aspirations were not hardwired into contracts and CRCs have had to make some hard choices… between whether they keep staff or whether they keep paying other providers for services,” Dame Glenys said.

“In some CRCs, staff numbers have been pared down in repeated redundancy exercises, with those remaining carrying exceptional caseloads.”

The companies have been left struggling by a funding model that predicted revenue far greater than that being received, following unanticipated changes in sentencing towards less profitable options.

Some CRCs are suffering significant losses through the “financially unattractive” contract, the inspectorate found.

Dame Glenys said that although it would be “impractical to suggest pulling the plug” on the failing system, there must be “a sustainable model and for these services to improve”.

“It’s a matter for the Government to decide where it goes next,” she added.

Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, said campaigners had foreseen the emerging “public safety disaster” of privatisation.

Hoping the damning report was “a large and rusty nail in its coffin”, she added: “Breaking up the public probation service, with a large part of it handed to private companies, created a fragmented, two-tier system that was never going to work.

“The problems stretch far beyond worries about funding – this is a fatally flawed model.”

Richard Garside, director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, said many had warned against the “ill-conceived” privatisation effort.

“The Government now needs to be as determined in remedying the problems in the probation system as it was in creating them in the first place,” he added, calling for the establishment of a unified public sector service.

David Lidington, the Justice Secretary, said: “It is reassuring that the NPS - which supervises high-risk offenders - is doing a good job overall and we will use this incisive report to continue improving it.

“We have already changed CRCs contracts to better reflect their costs and are continuing to review them. We are clear that CRCs must deliver a higher standard of probation services.”

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “Our reforms to probation mean we are now monitoring 40,000 offenders who would previously have been released with no supervision at all.

“Probation officers use their professional judgement to assess the level of supervision an offender needs.

“In some cases, lower risk offenders can be supervised by telephone after a thorough, face-to-face risk assessment, and their continued suitability for this type of monitoring will be kept under review.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks