Refugee Week: The Huguenots count among the most successful of Britain's immigrants

Fleeing oppression after 1685, tens of thousands of French Protestants came here to start again. Now, with Refugee Week on us, and a "Huguenot Summer" looming, Boyd Tonkin explains how much they contributed to British life

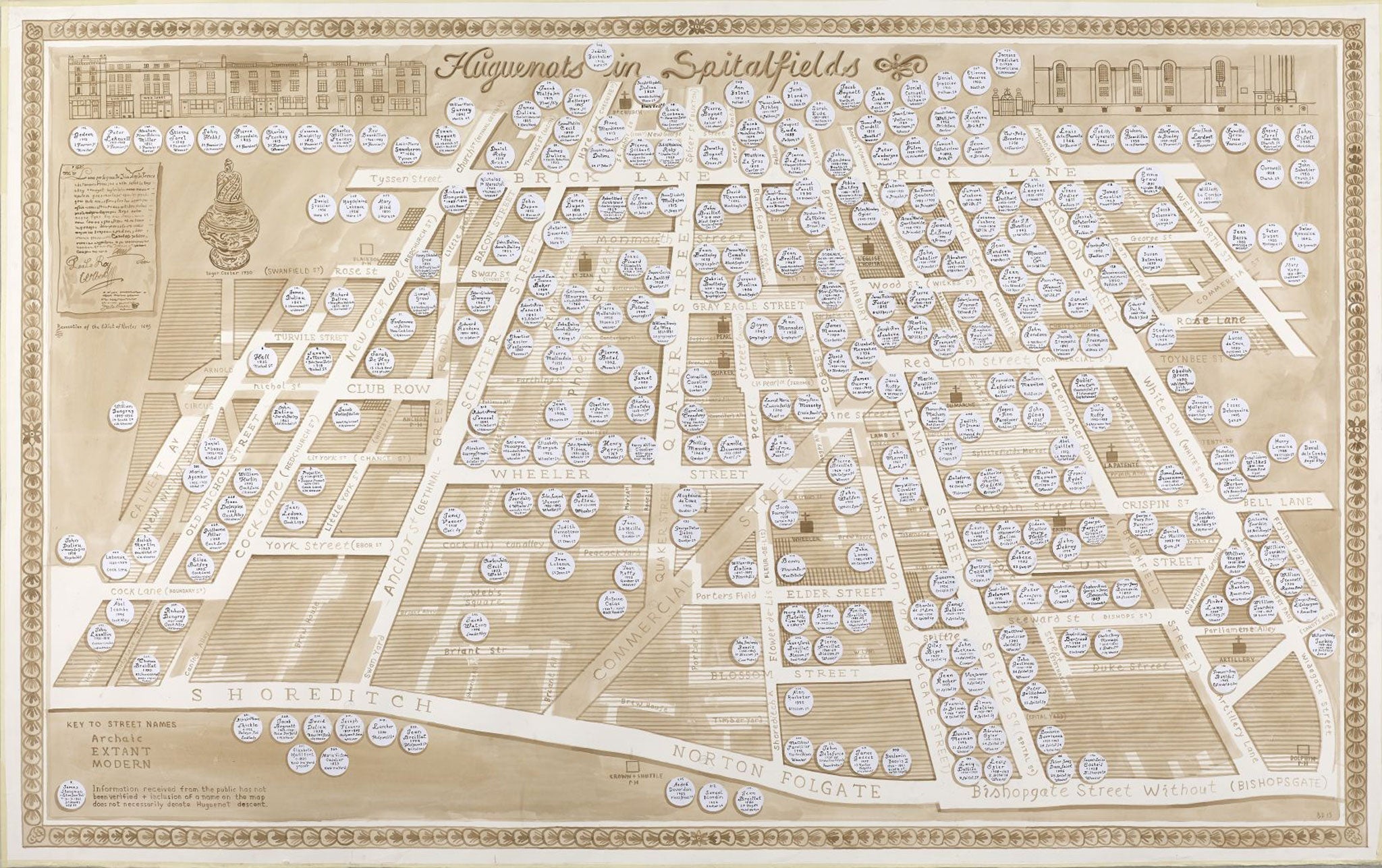

In the handsome 1720s house on Fournier Street where she runs an antique business and café, Fiona Atkins unrolls a large and beautifully detailed hand-drawn map. Created by the artist Adam Dant, it records the addresses of around 300 Huguenot families who lived in Spitalfields.

They were part of the great wave of French Protestant migration that transformed London, and England, after Louis XIV had in 1685 cancelled the civil rights granted them by the Edict of Nantes. At first, she had wondered whether many Huguenot descendants knew or cared where their ancestors had lived. Battalions of them did. "People were very engaged with the project," she reports. "I'm proud to have done it."

The map is just one of 100 or so events in this year's "Huguenot Summer" season. It remembers and celebrates their contribution, not only to London but 20 towns where the French settled – from Canterbury to Norwich, Plymouth to Rochester (where a Huguenot museum has opened and the "French Hospital" still reserves its almshouse accommodation for their descendants). Organiser and Spitalfields resident Charlie de Wet, who staged her first festival in 2013, has just returned from a talk in Plymouth. There, after the diaspora took root, "a third of the population were Huguenots, and nobody knows about it".

When she started to arrange Huguenot-themed events, she "began to realise that people didn't know the value of the Huguenots, or what their contribution was". With the Bishop of London Richard Chartres (another Londoner of Huguenot lineage) as its patron, and Spitalfields neighbour Dan Cruickshank as trustee, Huguenot Summer aims to spread their remarkable stories. "All we want to do," Charlie de Wet says, "is to give them credit for what they have done." That means engaging young people with the spirit of the weavers, joiners, smiths and merchants who set up shop in Soho or Spitalfields. At London Metropolitan University, textile and design students now study some of their crafts, such as silk-weaving, silversmithing and upholstery. "It's wonderful," she says, "to see 18-year-old international students learning the skills of the Huguenots."

This week is Refugee Week across the UK. As part of Huguenot Summer, a daily walk through Spitalfields will summon the ghosts both of the Huguenots and other migrants who followed in their East End footsteps. On Brick Lane, the walkers will pass the elegant temple that serves as the ultimate monument to London's diversity. Built in 1743 as the Nouvelle Eglise for Huguenots, in 1809 it became a Wesleyan chapel; in 1898 the Great Synagogue of Spitalfields, and in 1976 the Jamme Masjid for the district's more recent Bangladeshi incomers.

Still a lightning-rod for collective anxieties, the word "refugee" entered the English language when the Huguenots landed. Although migration had begun beforehand on a modest scale, around 50,000 French Protestants came to England after Louis XIV revoked the 1598 Edict of Nantes at Fontainebleau in October 1685. Another 10,000 fled to Ireland, part of an exodus of perhaps 200,000 people. Other large contingents went to Holland, Sweden and Prussia. That still left the bulk of a hard-pressed but robust population of 750,000 or so to weather hardship in France and wait for more tolerant times.

The Revocation capped an escalating assault on Huguenot liberties as the Sun King began to believe his own absolutist propaganda. Geoffrey Treasure, author of The Huguenots, calls it "the Versailles effect: the blinkered vision, the appeal of the grand gesture, the naivety in judgement that came with over-confidence". Particularly oppressive were the "dragonnades": the domestic terror whereby soldiers with a licence to bully, plunder and abuse were forcibly billeted on Protestant homes. With the Fontainebleau edict, Protestant ministers were given a fortnight to convert or leave. But it confirmed a strict ban on emigration for the laity, with harsh penalties: the galleys for men; the convent for women. So, pastors apart, the Huguenots were never "expelled". The legions who fled broke the law of the land that had rejected them. Hundreds of thousands left in haste and at risk, most of them no more secure of their future than the desperate human tide we see today in the southern Mediterranean. An early English account specifies that many refugees had "run great hazards at sea".

If you want hard evidence of the lasting trace that Huguenot migration has left on British life, glance at your purse or wallet. For 270 years after 1724, the Hampshire paper firm of Portal had – literally – a licence to print money; only in 1995 did the security-printing giant De La Rue take over the family business. Its founder Henry Portal opened his mill at Whitchurch in 1712. Within a decade he had found his fortune through the banknote paper contract. Yet in 1685, Henri de Portal and his brother, Pierre Guillaume, were terrified refugee children smuggled out of France in wine casks and sent on a perilous sea voyage. It took the young Portals from Bordeaux to Southampton.

Their father Jean Francois de Portal, a senior civil servant in Poitiers, had, like many Protestants, scented the looming danger. He planned escape, even before the Revocation.

If you were feeling flush, that wallet might until April 2014 – when the issue was discontinued – have contained a £50 note bearing the features of Sir John Houblon. Also the child of Huguenot refugees, Houblon served as the first governor of the Bank of England – set up in 1694, when Huguenots contributed around 10 per cent of its capital. And if the small print on banknotes defeats you, perhaps it's time for a trip to Dollond and Aitchison. Born into a family of Huguenot silk weavers, John Dollond founded his firm of opticians in 1750.

According to one estimate, one in every six Britons has some Huguenot ancestry. Names of obvious French origin tell only a fraction of this tale. Yes, it's easy enough to spot a Laurence Olivier, a Simon Le Bon, a Walter de la Mare, a Daphne du Maurier, a Samuel Courtauld, a Jon Pertwee, a Reginald Bosanquet, an Eddie Izzard, even – as the Ukip leader happily acknowledges – a Nigel Farage. Yet, just like Jewish incomers two centuries later, Huguenot migrants often changed their names or had them changed by impatient clerks.

As a Victorian history of London puts it, "the Lemaitres called themselves Masters; the Leroys, King; the Tonneliers, Coopers; the Lejeunes, Young; the LeBlancs, White; the Lenoirs, Black; the Loiseaux, Bird". By 1710, at least 5 per cent of the population of London – then around 500,000 – were French Protestants. In the French enclaves of Spitalfields and Soho, that proportion rose sharply. London soon boasted 23 French Protestant churches. Within a few years, a society totally unacquainted with mass migration had given a home to the equivalent – in terms of today's population – of 650,000 new arrivals.

In the rosy glow of hindsight, the Huguenots often look like the ideal refugees. "In sheer diversity and value," argues Geoffrey Treasure, "they must count among the most successful of immigrants." Jerry White, a leading social historian of London, confirms this: "What was striking about the Huguenots was the extraordinary diversity of their manufacturing, scientific and artistic specialisms. They were able to fill a huge vacuum, in a country where we didn't have much of that stuff."

From their famous forte of silk-weaving to hatmakers (a speciality in the community of Wandsworth), goldsmiths, printers, bookbinders, watchmakers, jewellers, paper-makers, gunsmiths and cabinet-makers, French expertise either kick-started or revitalised the entire gamut of high-skilled trades in England. Scientists and intellectuals also boosted innovation.

Denis Papin from Blois, for instance, invented the pressure cooker and designed an early piston-driven steam engine. Perhaps unwittingly, the migrants also incubated a certain kind of Francophile cultural cringe that continues to this day. "In Spitalfields," the historian of the Huguenot diaspora Robin Gwynn records, "it was noted that the refugee craftsmen decorated their houses with a taste rarely displayed by their English counterparts". Jerry White affirms that "almost all migrations bring something" to the hosts. But he agrees that "the very richness of the Huguenot gift to London and to Britain is difficult to mirror" in any later settlement. Charlie de Wet chooses the word "wonder" as a key to the response they elicit: "We wonder at their commitment, their faith, their bravery and their talent."

Yet all English arms did not stretch out to greet this sudden influx. Until the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 brought William III from Holland to the English throne, Charles II and the Catholic James II – both secret clients of Louis XIV – had hesitated to antagonise their patron across the Channel. Inevitably, the French migrants also ran into the usual complaints from home-grown tradesmen about unfair competition. As early as 1631, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers had objected that its members were "exceedingly oppressed by the intrusion of French clockmakers". However, a good many of the more specialised crafts that they practised scarcely had any pre-existing English workshops. As Jerry White points out, "Many of the luxury trades in London were the province of foreigners anyway. Look at painting."

Neither, for a long time, did the law do much to clear a path to integration. Only in 1708 did a "Foreign Protestants Naturalisation Act" offer most Huguenots citizenship rather than the halfway house of "denizen" status. For its part, the Church of England hierarchy looked with suspicion on their Calvinist worship and, at least until the 1690s, pressed hard for French conformity to Anglican rites. Over in bohemian Soho, the French easily slipped into the CofE; but "here in Spitalfields", says Charlie de Wet, "we were more Calvinist".

As co-religionists – more or less – to the English majority, the Huguenots did benefit from a fairer wind than most incomers. White reports that "the only experience of collective resentment I've come across is a little rioting around Spitalfields at the end of the 17th century". Nobles raised huge sums to succour the refugees and, in 1693, King William and Queen Mary gave them £39,000. The last Huguenot pensioner to draw on this royal bounty died only in 1876.

How much harm did the self-inflicted wound of the Revocation do to the French state – and how much did Britain benefit? At the time, not least in France, plenty of observers feared that Louis had committed economic suicide by driving away his most productive artisans and entrepreneurs. At Versailles, the Duc de Saint-Simon confided to his gossipy diary, with a degree of hyperbole, that the Revocation had for no good reason "depopulated a quarter of the kingdom, ruined its commerce and weakened it in all parts". Quite a few pragmatic Catholics agreed. Even Pope Innocent XI was unimpressed.

Certainly, the losses in resources to Protestant areas were drastic. "Towns like Dijon, Tours, Nimes and Rouen lost more than half of their workers," reports Treasure, "Lyons all but 3,000 of 12,000 silk workers". Meanwhile, from market-gardening to optics, almost every sector of the English skilled economy enjoyed a tonic injection of craft and capital.

For Jerry White, "Undoubtedly France was the poorer for it, and Britain the richer". Other historians downplay the impact of the diaspora and treat the more ambitious claims made for it as Protestant propaganda. Still, after decades of study, Robin Gwynn concluded that "the flight of the refugees damaged Louis XIV's government to a much greater extent than is now generally allowed". More broadly, the Revocation does look like the moment when the "Gloire" of the Sun King ceased to shine so brightly. France would spend much of the period from 1689 to 1714 locked in combat – often on the losing side – with the Protestant powers of Europe. They never lost an opportunity to invoke the fate of the Huguenots.

In England, beyond the windfall boom in arts and crafts, a long-lasting narrative took hold. It cast the nation as a safe haven; a welcoming refuge for peaceable and hard-working exiles from tyranny. To Jerry White, the Huguenot-enriched British could say: "We are open for business to people unjustly deprived of their birthright at home." He adds a caveat: "I think that's beginning to fade now."

'Huguenot Summer' is running until September: view the full programme at huguenotsofspitalfields.org. The Huguenots of Spitalfields map is available for viewing at the Town House, 5 Fournier Street, London E1 6QE, until 31 July: townhousewindow.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments