The Big Question: Has the congestion charge been effective in reducing London's traffic?

Why are we asking this now?

Ken Livingstone yesterday announced the most wide-ranging shake-up of the London congestion charge in its controversial history. The capital's Mayor is proposing that the daily fee, which next week marks its fifth anniversary, would more than triple to £25 for gas-guzzling vehicles. Meanwhile, the levy could be scrapped altogether for the most environment-friendly vehicles.

The scheme – a key pledge in Mr Livingstone's mayoral election manifesto in 2000 – has quickly become part of everyday life in central London and is much studied by other cities around the world desperate to tackle congestion. Opinion remains divided over its effectiveness, and the charge is rapidly developing into a major issue in the battle for the mayoralty in May.

How does the scheme work?

The revolution in London's transport system began at 7am on 17 February 2003, when a network of closed-circuit television cameras started capturing the registration numbers of motorists entering the City or the West End. Drivers have until the end of the day to pay the fee, which was originally set at £5 per day and rose to £8 in July 2005.

Last year, the charging zone was extended, despite strong opposition in local consultation exercises, to take in western Westminster, as well as Kensington and Chelsea.

Has it cut traffic?

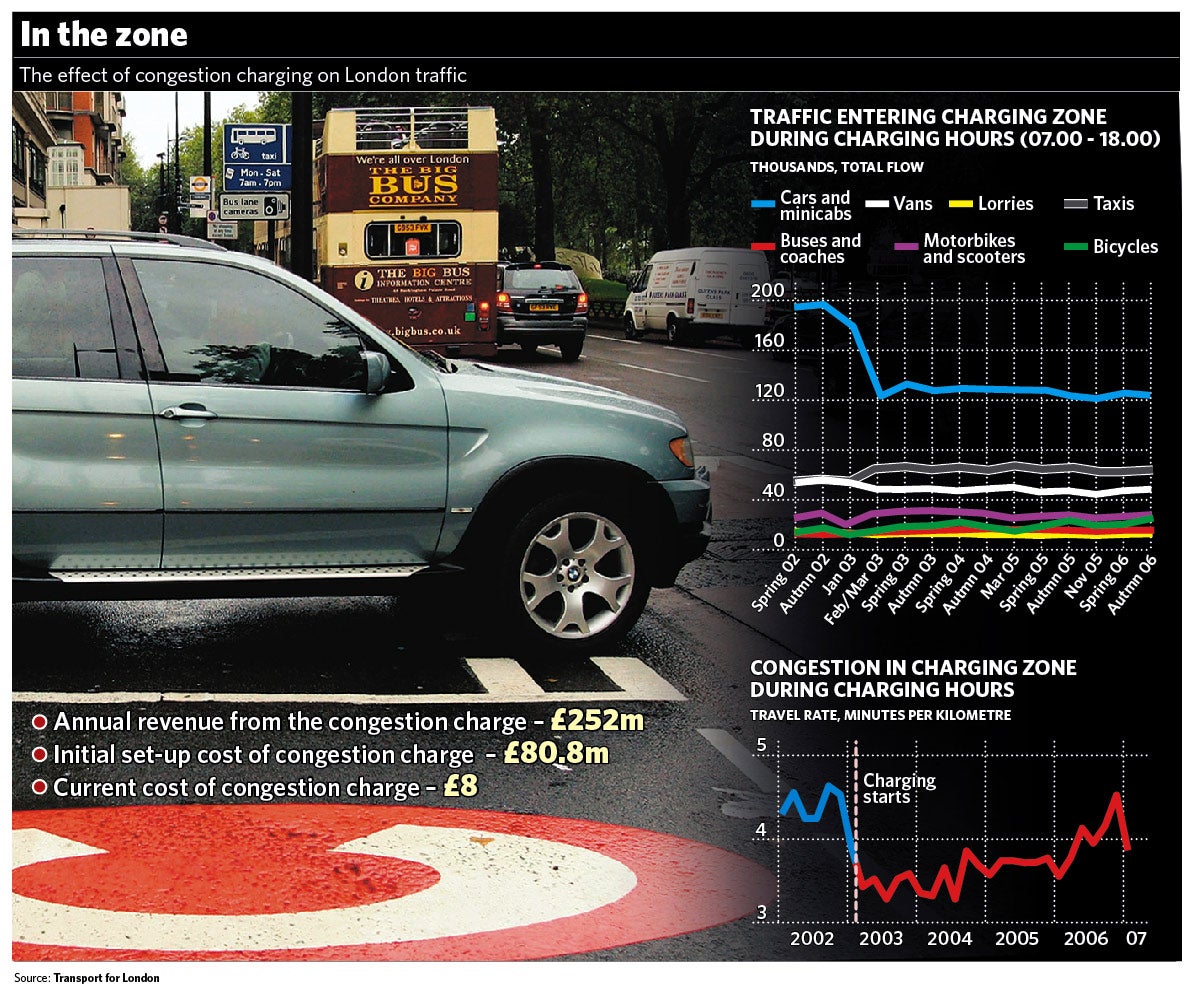

At the end of the last decade, London suffered some of the worst congestion levels in Europe. The introduction of the congestion charge had an immediate impact, reducing the amount of traffic in the heart of the capital by about 15 per cent.

About half the drivers who left their cars at home took public transport instead, with the rest getting a lift, using motorbikes or cycles to get to work or avoiding the area altogether. Transport for London (TfL), which administers the scheme, said the overall amount of traffic fell by 21 per cent between 2002 and 2006. The result is that 70,000 fewer vehicles are on the streets every day than before the charge began.

Meanwhile, the number of taxis has risen by 13 per cent, bus and coaches by 25 per cent and bicycles by 49 per cent, confirming significant changes to London's transport patterns over the past five years. TfL says the extension of the charging zone to the West has produced a fall in traffic in the area of between ten and 15 per cent.

So does this mean less congestion?

Not necessarily. There was a drop in congestion (defined as excess delays per kilometre) of 20 to 30 per cent after the introduction of charging. TfL also claims that average traffic speeds in central London would have fallen from 10.6 mph in 2003 to 7.1 mph in 2006 but for the scheme. But the reduction in congestion has not been sustained and, to the dismay of transport experts, traffic snarl-ups appear to be slowly returning to the capital.

Despite fewer cars being on the roads, congestion rose markedly between 2005 and 2006. TfL suggests the unwelcome increase has been caused by a surge in street works, including the replacement of water and gas mains and construction of bus lanes. Peter Hendy, the commissioner of Transport for London, said yesterday: "If we had the volumes of traffic that were there before the scheme started, we would be in serious trouble."

What is the revenue from the scheme used for?

Last year, drivers handed over £252.4m in congestion charge payments to TfL, a fractional fall on the previous 12 months and just under 10 per cent of its total income. Running the scheme cost £130.1m and, when other costs such as administration and depreciation were taken into account, TfL was left with a net income of £89.1 m from the charges.

The organisation is required by law to reinvest its "profit" into public transport in the hope it will help create a virtuous circle, tempting former drivers back on to buses. All in all, the money is a welcome fillip for the system, even if it is significantly below early claims that £130m a year could be raised.

Has business in London suffered?

Many retailers were hostile to the congestion charge from the start. John Lewis blamed the levy for a 7 per cent drop in takings at its flagship Oxford Street store in 2003, while the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry reported that 25 per cent of businesses were considering moving outside the zone.

Colin Stanbridge, the chamber's chief executive, said yesterday: "We are still of the view that the charge has had a really bad effect on retailers, particularly small retailers." He fears its long-term impact will be to change the mix of shops in central London as shoppers look to out-of-town retail parks for their larger purchases.

"If you are buying anything bigger than a toaster, you don't want to take it home on the Tube or bus," he said. TfL countered that it had no found evidence that businesses were suffering because of the charge.

So what is the future of the charge?

It will remain, in one form or another, whichever party wins the mayoral election in May. If Mr Livingstone gains a third term in office, drivers of the most polluting vehicles, such as 4x4 "Chelsea tractors", people carriers and high-performance sports cars, will have to fork out £25 a day from October. At the other end of the scale, vehicles with the lowest carbon dioxide (C02) emissions would be allowed to enter central London for free.

What is the mayor's case for raising the charge for some vehicles?

Mr Livingstone explained: "The C02 charge will encourage people to switch to cleaner vehicles or public transport and will ensure that those who choose to carry on driving the most polluting vehicles help to pay for the environmental damage they cause. This is the 'polluter pays' principle."

Boris Johnson, the Tory mayoral candidate, has dropped his party's opposition to the charge. But he wants it to undergo radical surgery, and has promised to scrap the western extension and introduce a "fairer" pricing structure. He said of Mr Livingstone's proposals: "Londoners use their cars because of the appalling state of the transport system. A big car tax won't change that. We need better alternatives to get out of our cars – especially those who live in the outer boroughs with bigger families, many of whom cannot afford to swap cars."

Brian Paddick, for the Lib-Dems, also wants to consider getting rid of the western extension, with a new focus on the central zone, where "traffic grinds to a halt on an almost daily basis".

So has the charge achieved its aims?

Yes...

* Levels of traffic in London have fallen sharply at a time when overall car ownership is rising

* More people are now using environmentally-friendly transport such as buses and Tube trains

* Traffic congestion in central London is not as bad as it was a decade ago

No...

* Business leaders say that the congestion charge has adversely affected the takings of retailers

* The capital's streets have not been transformed – despite the reduction in traffic jams

* Not as much as cash has been raised from the congestion charge as was originally hoped

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks