The Big Question: What are the new proposed rape laws, and why are they so contentious?

Why are we asking this now?

This week, Harriet Harman, Labour's deputy leader who is standing in for Gordon Brown while the Prime Minister is on holiday, vetoed a long-running review of rape laws at the eleventh hour, complaining that they failed to address the concerns of women.

Chief among those is the fact that, despite an estimated one in 20 women having been raped, only one in six of those reports the attack to police. And, of those, seven in 10 cases never make it to court. Conviction rates for rape remain stubbornly low at 6.6 per cent, which campaigners say increases the stigma attached to reporting sexually abusive incidents and relationships.

What's the problem with the present law?

Aides to Harman, the Equalities Minister, emphasise the fact that the laws in relation to rape are not the primary or sole worry; rather it is the post-rape experience of victims. Harman feels that not nearly enough is done to address their trauma, while the low conviction rates discourage women from coming forward.

There are four areas that Harman would like to see improved in particular: how complaints are made; how alleged victims are treated by police; what support services are available to victims; and the handling of convictions in court.

It is worth noting, however, that only five years ago, sex laws in Britain underwent the biggest reforms for a century – which is one of the reasons ministers are so anxious about persistently low conviction rates. The law on consent was hugely strengthened by creating a definition of it, while the defence that a person should avoid conviction if there was an honest but mistaken belief that consent had been given was removed altogether.

Largely welcomed as radical steps upon their introduction, these changes were designed to make grey areas less grey. Campaigners maintain that much more needs to be done.

What's the feeling across the rest of the Cabinet?

Harman wants so-called root-and-branch reform of the present laws, and in this enterprise she has the support of Vera Baird, the Solicitor General. But she appears to face opposition from the Justice Secretary, Jack Straw, and the Home Secretary, Alan Johnson.

The disagreement centres on the terms of reference: how far should the reforms go? Straw and Johnson, perhaps with one eye on the possibility that their time in government is approaching its conclusion, wish to limit the scope, so as to ensure changes can be made effectively before next year's general election. Harman, Labour's most senior female member, wants to be bolder.

Alleged splits within the Cabinet are often overstated, but the remarks of the Police Minister David Hanson yesterday are as clear an admission as could reasonably be expected of divisions at the top of government. "Sometimes government has discussions that the public are not aware of... We are looking at a whole range of issues. Government is sometimes about discussing issues. We have more work to do".

He spoke on a visit to a newly completed sexual assault referral centre at St Mary's hospital in Manchester, where Harman would have made an announcement, were it not for the split.

What will any new measures entail?

Among the more contentious of the new proposals were conviction targets for prosecutors and police, which immediately rubbed up against the obvious objection from those who would be subject to the targets that undue pressure could distort the law. Whether or not Harman really was interested in advancing these ideas is unclear; yesterday the Home Office suggested they were not her priority.

It does seem she was keen to re-examine the contentious area of consent. The Home Office has promised police that it will scrap all targets beyond the singular objective of increasing public confidence in their force. There is a wearily familiar sound to the promise of new training schemes for police unaware of how to respond to a rape incident, but yesterday Hanson did announce £3.2m extra funding for a network of eight sexual assault referral centres, similar to the Manchester model.

How does Britain fare in dealing with rape?

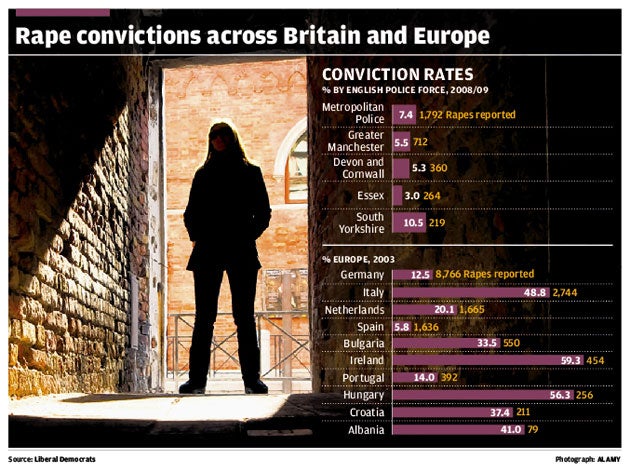

A huge amount of effort has been put into encouraging women to come forward if they feel they may have been sexually assaulted. This has worked considerably: in 1997, 6,281 women came forward, whereas last year 12,165 did. The contrast with the rate of convictions is stark. At the end of the 1980s, the conviction rate was 19 per cent, whereas it now hovers at 6.6 per cent.

In Scotland the rate is still lower, at 2.9 per cent. The first Europe-wide study of rates of convictions ranked Britain bottom of 33 countries, while finding the proportion of false allegations "extremely low" – ranging from between two and nine per cent. According to the charity Rape Crisis England and Wales, in 2003-04 the cost to our economy of sexual offences was £8.5bn, or an average of £76,000 per rape, made up of lost output and costs to the health service.

Campaigners say that women still cannot rely on a fair hearing from police, which they claim may be because most victims are women and most police are men. A culture of disbelief still prevails, they claim, and delays, or disinterest, among police officers can result in vital evidence being lost.

Why is Harman being so outspoken?

Much of the discussion surrounding this issue has focused on Gordon Brown's deputy. Over the weekend she suggested that the severity of the financial crisis in Britain would have been lessened if more women had been on the boards of leading banks. This followed colourful speculation that she and Lord Mandelson had emerged as the leading contenders to succeed Gordon Brown, and were now engaged in that curious thing, a "battle for Labour's soul". Certainly, by being vociferous in pursuit of her equalities agenda, Harman forges a connection with Labour's grassroots, a significant number of whom are northern and working class (whereas she is a privately educated southerner). But there is a less cynical interpretation of her enthusiasm for reform too: Harman is the most senior woman in a Labour Party whose leading female lights – Jacqui Smith, Ruth Kelly, and Hazel Blears – have left the Cabinet recently, and she has long championed women's rights. If ministers are agreed that there is a major problem with rape convictions, what is wrong with being radical to fix it?

So when can we actually expect some changes to rape laws?

Politics tends to slow down in August, when many ministers are on holiday. Yesterday, Hanson said that he hoped the Government would make an announcement in September or October. A low-key "implementation review" by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary, looking at guidance for police and prosecutors, will publish a report – but not until after the next general election.

Will new rape laws be introduced to improve conviction rates?

Yes...

* The conviction rate is so stubbornly low that ministers will have to improve it through tougher laws.

* Harriet Harman could use her influence at the top of Labour to push through her equalities agenda.

* Even the radical overhaul of rape laws introduced five years ago has not proved sufficient.

No...

* Jack Straw and Alan Johnson will not allow "root-and-branch" reform to take place.

* The most radical approach may be to change support services rather than update the letter of the law.

* Proposals to set targets for police and prosecutors put unacceptable pressure on them to bend the law.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks