The controversial 'mega-dairies' that alarm campaigners and divide a struggling sector of British agriculture

Despite opposition, huge confinement units housing thousands of cows all year round are popping up across the UK

In a quiet corner of the English countryside lies a farm. It is almost completely hidden from public view - a private road leads up to the facility, dominated by several vast steel-framed buildings and conical feed silos.

It is a scene that has become typical in Britain’s modern farming landscape - a livestock factory dedicated to the production of animal products with the highest possible efficiency.

But these farms do not rear poultry or pigs. They are intensive dairy units. This one is home to at least 1,300 cows which, contrary to the popular image of milk production, do not graze in the fields which surround the farm. Instead, they are confined - in some cases all year round - inside a series of huge open-sided barns capable of holding up to 400 animals each.

Row upon row of cows are standing or sitting in one of the scores of metal cubicles that run the length of the barns, or wandering around the walkways in between. As there is little or no outdoor grazing permitted, feed and water and everything else the animals need is brought directly to them.

Three times a day, the herd is milked in a state-of-the-art automated milking parlour, capable of handling 380 cows per hour. The milk obtained is transferred into two large tanks - total capacity 50,000 litres - before beginning its onward journey into the food chain.

Outside, adjacent to the main barns, a row of white boxes, with straw bedding and a small wire enclosure for each, provide a temporary home to the latest additions - female calves - that will enter the main herd as replacements for those cows that have reached the end of their productive lives.

Nearby, two dedicated waste lagoons store the sizable volumes of slurry that the shed-bound cows generate. The waste will be deposited onto land surrounding the farm.

It is an industrial scene a world away from the popular perception of British dairy farming and the image portrayed on many cardboard cartons at the breakfast table where cows roam on green pasture and a milk churn stands at the farm gate.

An investigation by The Independent has revealed how an increasing number of UK dairy farmers, some struggling in the midst of the ongoing milk-price crisis, have begun operating highly-intensive US-style farms where cows are kept permanently indoors throughout the year.

Those behind these hyper-efficient dairies insist that what they have set up is a sustainable, economically-viable and welfare-friendly model for a struggling sector of British agriculture buffeted by the winds of global trade and the cut-throat nature of the competition between supermarkets.

Backers of these “mega-dairies” point to evidence showing how animal health can be improved with the constant surveillance and management of the units with round-the-clock monitoring by herdsmen and veterinary care.

But campaigners have warned that this new industrialised model of milk production could help bring about the end of traditional dairy farming, pointing to the experience in the United States where intensive dairy farms - known as confinement units - are increasingly common. Those housing 700 cows or more are classified as CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feedlot Operations) and the largest in America house up to 36,000 cows at a time.

The first attempt to bring CAFO-style farming to Britain ended in uproar five years ago. Plans for an intensive 8,100-cow "mega-dairy" at Nocton, Lincolnshire, had to be abandoned following a national outcry and objections that the facility could pollute drinking water supplies.

But campaigners are concerned that despite this setback, the industry has been intensifying “by stealth” - slowly building up larger farms which they fear will lead to environmental problems and change the face of British farming, even though there is nothing illegal about such intensive farming and nor any suggestion that the farmers are breaking the law.

Official figures on the number of dairy farms operating intensively are vague - estimates range between five and 10 per cent of the total. Neither the National Farmers Union nor the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) hold a definitive record of numbers.

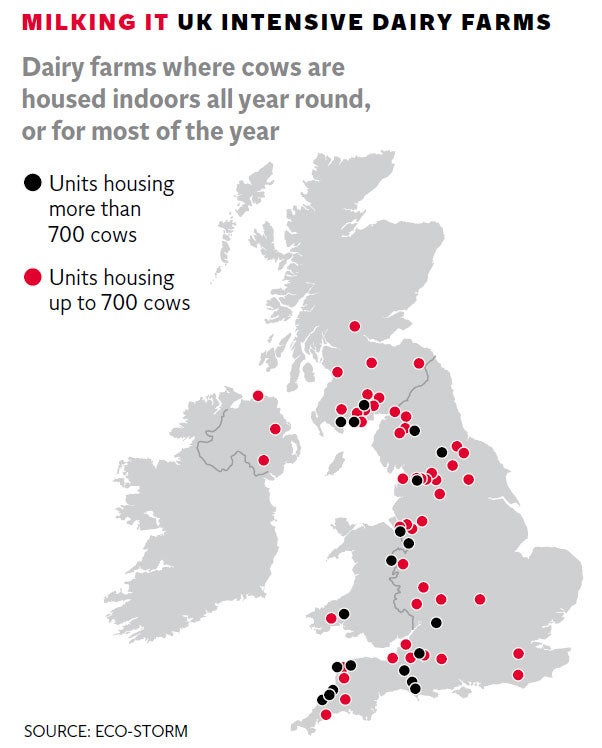

But an investigation by The Independent has identified dozens of such farms operating across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, pinpointing - for the first time - at least 50 confinement units, and 20 CAFO-style facilities. More are understood to be in the pipeline. The largest units hold over 2,000 cows, in comparison to the average UK herd size of around 125.

Although this new breed of intensive farms span the length and breadth of the UK, from Sussex to Lanarkshire to County Antrim, the majority have been established in traditional milk production hotspots - Devon and Cornwall, Cheshire, Lancashire.

All have been confirmed as housing some or all of their animals indoors year-round - or, in a few cases, for the majority of the year - in contrast to many conventional dairy farms which typically allow their animals to graze for up to half of the year.

Opponents of intensive dairies say the facilities risk polluting water and soil, compromise animal welfare and blight the lives of local people with extensive slurry spraying and a constant stream of farm traffic and tankers.

Ian Woodhurst, a campaigner with World Animal Protection, said: “There are a wide range of environmental impacts from any intensive livestock system. Our focus is on the welfare of cows in intensive dairy units, because of evidence that cows face an increased risk of udder infections and lameness, and because their natural behaviours are inhibited and restricted.”

British farmers themselves appear divided over the intensification issue - some are worried about the negative image that intensive farming can produce. Yet others believe that the current economics of milk production - with wafer-thin margins and fluctuating milk prices - make scaling up to more efficient, higher-yielding farms not just an attractive proposition but one of a rapidly-disappearing number of means of survival.

Television screens and newspapers have been filled with images of protesting farmers blockading milk depots, cows being paraded through supermarkets, and warnings from farming leaders about the consequences of the ongoing milk crisis, where farmers are being forced out of business because of the low price of milk.

The crisis is centred around the fact that many farmers are forced to sell milk for less than it costs them to produce it. Figures released earlier this year revealed that whilst many farmers were receiving 23.66 pence per litre of milk - and some as little as 19p - it was costing them between 28p and 32p per litre to produce.

The result has been incidences where milk is being sold in supermarkets for less per litre than mineral water and losses that many farmers cannot afford.

A complex combination of factors - supermarket price wars, global overproduction and a drop in demand from two key markets, China and Russia - has been blamed and the number of UK dairy farmers has continued to plummet. From more than 25,000 nationally in 2000, the number of dairy farmers now stands at less than 10,000 in England and Wales with an average of one leaving the sector every day over the last year.

The supermarkets, the UK Government and EU officials have scrambled to address the crisis with short term fixes - nearly all of the big retailers now pay a raised price per litre of milk; emergency financial packages; initiatives to open up (or re-establish) overseas markets. But for many the situation remains bleak, and each week more are forced to empty their farms and shut up shop.

In order to survive, farmers leaders say, stark choices must be made. Some borrow, some diversify, others expand or intensify in order to attempt to make production more profitable and efficient.

People love coming to the countryside and seeing the cows, seeing the lovely hedgerows, and what do they get? Smells, intensification, John Deere’s hammering down the road

The supporters of the CAFO-style units say that far from being environmentally damaging, they actually bring benefits, with waste slurry frequently being used for energy production. Anaerobic digesters, which turn waste into renewable energy, are becoming more common on large dairies.

Mike King, vice chairman of the Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers, said: “In many cases the larger dairies are able to employ their own animal health and husbandry specialists who enable the unit to achieve standards which would equate to those on any dairy farm, whatever the scale.”

But the arrival of the facilities has not been without problems.

In Wales, Cwrt Malle Farm, near the village of Llangain, Carmarthenshire, is home to around 2,000 dairy cows - making it one of the UK's largest dairies. The cows are housed permanently indoors all year round, with a 24 hour milking operation supplying around 68,000 litres of milk per day.

Local people have complained that the farm, which has expanded over a number of years, has made their lives a “misery”, with complaints about noise, odours and increased farm traffic - particularly tractors carrying slurry and milk tankers.

Gaynor Thomas, a Llangain resident, told the Carmarthen Journal: “The quality of life in some parts [of the village] has been so badly affected by the activities at Cwrt Malle. Mud all over the roads, foul smelling slurry all around and sometimes spilt in front of your property.”

The Independent has learnt that Cwrt Malle has been responsible for a number of pollution incidents in recent years.

Internal records from Natural Resources Wales (NRW), the Welsh equivalent of the Environment Agency, reveal officials have investigated - and verified - seven separate incidents involving waste from the farm since 2008, including one in which “serious farmyard slurry pollution” was reported.

In a Freedom of Information request, the NRW confirmed it had sent four official warning letters to the farm and prosecuted it for breaching environmental regulations. In 2013, Cwrt Malle Ltd was fined £5,000 and ordered to pay costs after admitting an offence under the Environmental Permitting Regulation 2010 in which silage effluent was discharged into a stream.

The farmer behind Cwrt Malle, Howell Richards - who has said that cows grazing in fields is an “almost nostalgic concept” - has defended his expansion, stating that large scale dairy farms have a key role to play in increasing UK dairy production, and in improving the fortunes of dairy farmers.

He told BBC News: “The backbone of British dairying will always be the family farms, as we are a family farm ourselves; the big difference will be that the family farm, where it used to be 40 or 50 cows today is 120 cows, maybe tomorrow [it will] be 150 cows. But it’s inevitable that people will milk more cows [and] become more efficient because like any other business you have to be efficient.”

Mr Richards did not respond to questions from The Independent. He has previously defended the operations of his farm, saying it offered higher welfare for cows with low rates of mastitis and better conditions for farmworkers, who work eight-hour shifts in an industry renowned for its long hours.

He told a conference last year: “In the past we’ve had people complaining about slurry spreading with splash plates, so now slurry isn’t spread anywhere near houses and we use an injection system.”

In north Devon, the Parkham Farms dairy, not far from the renowned holiday village of Clovelly, is an example of the way some producers have diversified to survive. It makes premium cheddar cheese for Tesco, amongst other customers.

Parkham Farms is run by Peter Willes, one of those behind the controversial Nocton “mega dairy” proposal in 2010. The company says it produces 4,000 tonnes of cheese a year, using milk from 6,000 cows.

Many of these animals are managed on 28 independent farms which sell their milk to Parkham but three large farms are operated by the company itself, including a CAFO-style unit of around 1,000 animals housed year-round at Beckland Farm, near Hartland.

Local residents claim the volumes of slurry being generated from the farms have at times turned fields where it is regularly disposed of into “open sewers”, and caused unacceptable odours and traffic in an area popular with tourists. It is, they say, Nocton “through the back door”.

One homeowner said: “People love coming to the countryside and seeing the cows, seeing the lovely hedgerows, and what do they get? Smells, intensification, John Deere’s hammering down the road.”

Members of a local campaign group, “Too Much Slurry”, accuse the farms of expanding “by stealth” and are currently objecting to a retrospective planning application for a waste lagoon at a facility built to house 1,000 cows.

Earlier this year, Mr Willes and the Parkham Farms Partnership were prosecuted in relation to a number of pollution incidents in 2014 and ordered to pay more than £30,000 in fines.

The farm strongly defended its operations, saying it was a responsible business employing 90 people that had acknowledged mistakes where they were made and worked with the Environment Agency (EA) to rectify faults. It said that it had admitted the breaches at the earliest opportunity and it had been acknowledged by the courts that no environmental damage had been caused by the incidents.

The company said it injected - rather than sprayed - waste into the soil in line with regulations, adding that the practice was a more sustainable way of fertilising land than using chemical fertilisers and the amount slurry was no greater than that from traditionally grazed cattle. It added that its planning application met the EA’s requirements.

In a statement, the farm said: “It is the case that the economics of the dairy industry, which are ultimately driven by consumer choice, necessitates larger herds and that keeping cows under cover - and in our case feeding them using grass cut from our own pastures - is often the most effective way of managing large herds. We pride ourselves on the quality of our products and the care of our herd.”

For the moment, the mega-dairies remain relatively small in number. But experts say British farmers should look to the experience in America, where CAFOs now account for a large chunk of dairy production, to see that intensive dairy production may become the norm.

The University of Wisconsin's Center for Dairy Profitability has found that, contrary to much conventional thinking, large farms are not necessarily more economically efficient than smaller farms.

John Ikerd, professor emeritus of Agricultural & Applied Economics at the University of Missouri, said: “Economically-speaking, the industrialisation of dairy operations in the UK will mean the end of dairy farming as you have known it, with the only long-run profits going to large investors and to the agribusiness corporations that ultimately will control animal agriculture if current trends are allowed to continue.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments