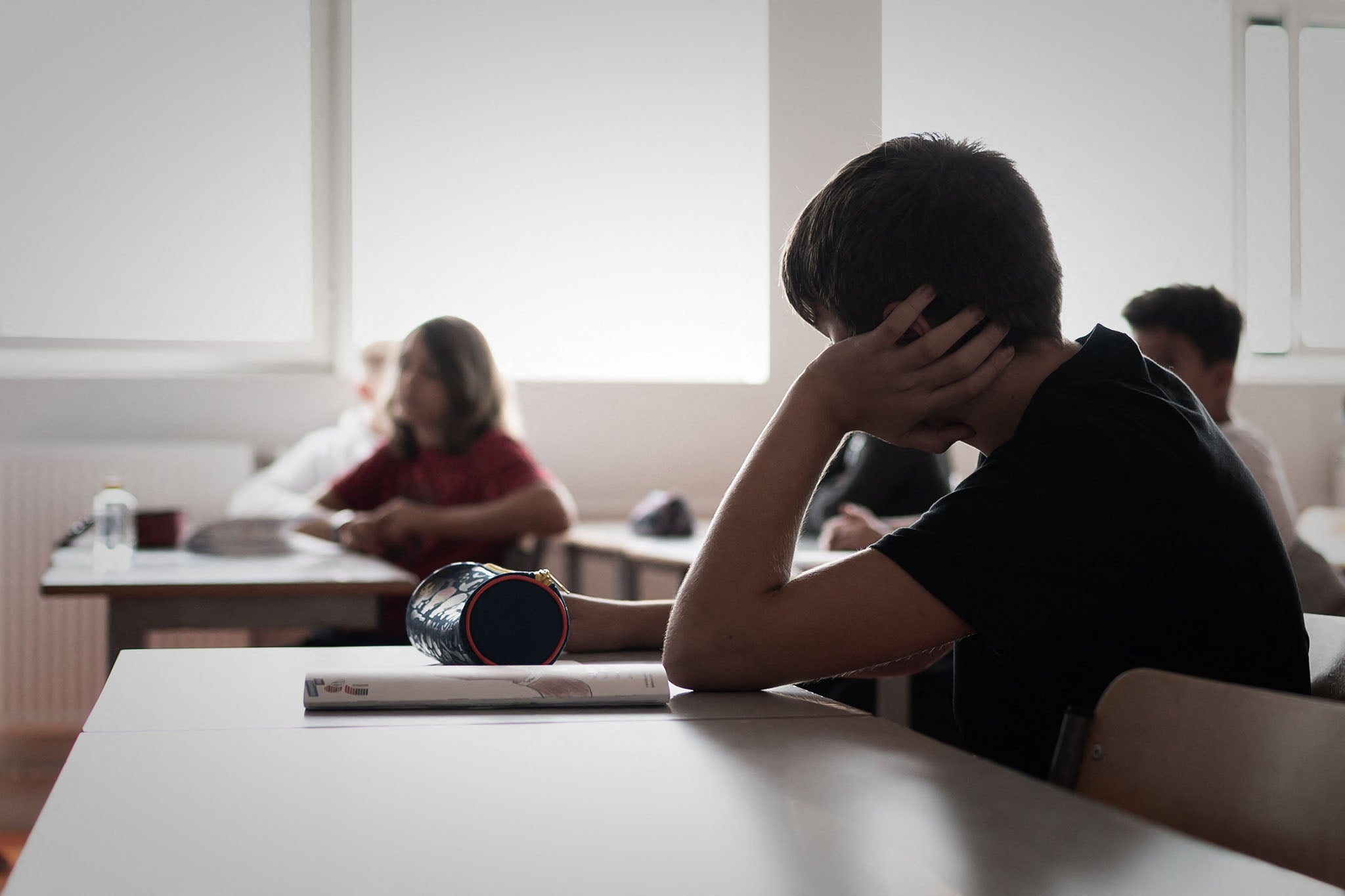

(Not going) back to school: Inside the UK’s epidemic of school refusers

Once, children who didn’t turn up at school were dubbed truants, their records were marked and parents were punished. But today, more than a million children and teens are persistently absent. Chloe Combi talks to them and their parents and asks how we got to a place where nearly 20 per cent of children don’t go to school

Reece* (13) hasn’t been to school for nearly 400 days. He should be starting year 9 on Thursday at his comprehensive school in northwest London, but he didn’t attend a single day of year 8 following year 7 when he began to “melt down every day before school”, according to his mother, Elaine. She has three other children, one of whom has special needs, and when I speak to her, she looks not just tired, but worn down.

She explains “I know people will say I’m a sh*t mum, people have actually said it to my face, and I know what’s said on social media, but I’ve tried everything with Reece – counsellors, talking to him, being nice, threatening him, I took away his PlayStation he screamed so much, the neighbours came round because they thought someone was being murdered. Even when the deputy head came round to try and get Reece, he screamed, spat and was so hysterical, it was impossible. I just don’t know what I’m going to do with him. I’m at my wits’ end.”

Reece is just one of the 1.28 million children and teens (roughly a staggering 17.9 per cent of the attending school population) who are persistently absent.

Persistent absence is when a pupil misses more than 10 per cent of their school sessions; severe absence is when a pupil misses more than 50 per cent. Reece would be counted as a school refuser, a pupil who doesn’t attend school due to complex behavioural reasons rather than disciplinary ones aka students who don’t attend because they just don’t want to or don’t perform well within the structure of school.

Fifteen-year-old Caleb should be starting year 11 at his comprehensive in Manchester, and thinks he attended “maybe one or two days” in the school week in year 10.

He explains, “I would go more, but I just get into trouble. I’d make myself a promise to be good, but then I get bored or didn’t understand what the teacher is going on about, start f***ing around, cause a riot, end up in isolation and my mum would cry or scream at me. Honestly, it wasn’t worth it, really. I think I learnt more by watching YouTube. I can’t get into trouble in my room.”

But the scale of the problem in the UK indicates there is a bigger issue at play than just school-shy kids who don’t fancy getting up with the alarm and adhering to the rules. Serial absenteeism has always been a problem, but it is impacting all kinds of children, for all kinds of reasons.

Reshma* attends an extremely competitive and over-subscribed girls’ grammar school in south London, is a high achiever and was on track to get all 8s and 9s at GCSE. She started suffering from acute anxiety and an undiagnosed eating disorder – she’ll only eat white and green food – and this has hugely impacted her school attendance. Her dad thinks she missed about half of every week in year 10 and has an arrangement with the school this term where she is allowed to take herself out of classes she finds stressful, go home for lunch and leave early on Thursday and Friday for private therapy.

I ask her dad what the therapy is going to cost and he wryly says, “about as much as a nice family car, but we’re lucky because we can afford it.” Not all families are so lucky and teenage mental health services like Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (Camhs) are so oversubscribed, there are waiting lists that can stretch to actual years, by which time symptoms and behaviours of suffering children and teens worsen.

The scale of anxiety being reported by schoolchildren is something we have never seen before. In the biggest ever survey of 16- and 17-year-olds for The Sunday Times, nearly 70 per cent of girls said they had skipped school because of mental health. Preparing for their return to education this week, the words they chose to describe their world were “difficult”, “challenging”, “stressful” and “scary”.

Anxiety was hugely exacerbated by Covid, when the nation’s kids were yanked out of school at a formative age under globally catastrophic conditions, when everyone was frightened, and tensions were running high both online and in the real world. Every parent I speak to pinpoints the Covid years as a trigger for either the starting point for school refusal or exacerbating existing behaviours that have made school more untenable for vulnerable kids. Making lessons accessible online during that time has also made it harder for schools to insist all pupils are physically present for lessons.

Reece’s mum squarely blames the pandemic. According to her, Reece “loved primary school, but became very anxious during the Covid lockdowns, thinking we were all going to die, and obsessively watching YouTube videos, and has never been the same since”. Caleb agrees with this and identifies the Covid-induced break in school in his formative years as highly destructive to his ability to cope with school. Remember, schools closed in March and many didn’t open again until September (theme parks opened before schools did) and, even then, classes were regularly disrupted due to mini-lockdowns and teacher absences. “Basically, getting a couple of years off school wrecked loads of us,” explains Reece. “It was so hard to go back. I was 10 when the pandemic hit, so by the time I got to high school, I was like, nope. Not going.”

Mental health is a major factor being identified by teachers, parents and students as a cause for the school absenteeism epidemic. Generation A and Generation Z are young generations fluent in the language of mental health and will openly discuss diagnoses and/or self-diagnose attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression and all kinds of disordered eating, behavioural and thinking patterns.

The fact that we treat mental health as seriously as physical health is a good thing, but it can present a new set of challenges for parents and schools, too. Reshma’s dad (who is very sympathetic to her challenges) believes that teenagers are very susceptible to suggestion and the excessive awareness of the mental health challenges of their friends and favourite influencers, and will mirror or self-diagnose similar behaviour – with real-world consequences

He explains, “Reshma was always quite an anxious kid, redoing already really good homework, obsessive tidying – which we never minded, actually! But when she got a phone, she started following these TikTok people who would all talk about their mental health diagnoses, one of whom was someone who was homeschooled because she couldn’t cope with school, and very quickly, Reshma started exhibiting similar behaviour. I don’t think it’s the whole reason for her struggles, but I think it’s part of it.”

And the consequences are being felt at a societal level, too. By the end of 2024, the number of Neets (16-24 year olds not in education or training) hit nearly 1 million – a 42 per cent increase over three years. Among these will be many school refusers who have missed so much of school that they weren’t able to sit exams or get the grades they would have been otherwise capable of. That is a lot of wasted potential of a group that the rest of us will be relying on in the future.

Ella Deanus is a family support manager at Southwest Partnership in Hertfordshire and works on the frontline of the teenage mental health crisis, going into schools in the borough and working one-on-one with students exhibiting a whole range of challenges – just one of which is school refusal.

They have real success in tackling the issue of serial absenteeism and school refusal and she explains, “you must have a triangulated approach – parents, school and the young person all working towards the goal of attendance. You need to look at the push and pull factors at home and school. For example, a love of art can push them to school; pull factors can be a friendship issue, so they hate lunchtime. An identified adult at school to support and liaise helps. Home life needs to be routine (visuals, written etc) and expectations clear – don’t give screen time if they’re supposed to be in school but if they go for an agreed time let them have their downtime.”

Huge numbers of kids aren’t coping within the traditional confines of the school system, but school budget cuts mean those critical needs aren’t being met

The national view of serial absenteeism tends to be dim with many believing a “just drag them to school” approach works, and the fact that it has festered as such a ubiquitous problem is a symptom of over-indulgent parenting – parents are largely identified as the culprits. But it’s usually so much more complex than parents who are too soft or just can’t be bothered.

Some are even of the view that school in the UK is an old-fashioned construct where hundreds, if not thousands, of young people are corralled for eight or so hours a day and are required to learn stuff many don’t understand, or genuinely struggle with – so it’s inevitable many don’t cope well with the system.

The Finnish school system, which is often held up as the gold standard, with the ability to view children as individuals with individual learning needs rather than a part of a monolithic system like ours. But even in Finland, there has been a small increase post-Covid with serial school absenteeism affecting about 2-3 per cent of the school population. This pattern is replicated across Europe with small increases in school absenteeism – but nothing like the scale of ours.

In the UK, it is clear we need to address the whole problem – but big problems require big solutions. Currently, we don’t have the resources to meet and support the scale of the child and teenage mental health crisis, and it goes without saying that there needs to be serious investment in more services for those young people and support for their families.

Huge numbers of kids aren’t coping within the traditional confines of the school system, but school budget cuts mean those critical needs aren’t being met and schools are in dire need of more special education teachers, classes and services like the ones Ella Deanus are her colleagues provide. Deanus also believes the early school years really need to be focused on as they form the foundation of good or bad school habits. She explains, “If it’s not caught early (as in really, really early), it’s really difficult to pull back, so schools and parents need to identify patterns early.”

As schools return this week after the summer break, the stress this puts on huge numbers of young people and their families shouldn’t be written off as “soft”, “woke” or “pathetic”. The distress of the parents and the kids dealing with serial absenteeism and school refusal is acute and we need to address it as part of the mental health crisis and a cracked and underfunded school system and not just kids who would rather play on the PlayStation than go to maths.

Elaine breaks down in tears when she tells me, “I’ve been told Camhs can’t even see Reece for an initial assessment for another five months, I know the start of term is going to be a non-starter for him, and I feel absolutely desperate and like a complete failure not being able to get him to something as basic as school.” There will be millions of parents who can relate.

https://www.southwesthertspartnership.org.uk

*Names have been changed

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks