Road to Brexit: The real players that will keep EU talks going

In the first of a series of Road to Brexit features, The Independent reveals the powerful players in the UK and EU’s negotiating teams

Personal relationships will matter when the complex negotiations over the UK’s withdrawal from the EU get underway next month. In public, the battle of wills will be between Theresa May and the 27 EU leaders, and between David Davis, the pugnacious Brexit Secretary, and Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief negotiator.

Yet much of the spadework will be done behind the scenes by little-known officials. Their role could prove crucial, especially when relations between their political masters hit turbulence.

Two senior officials might keep just the show on the road and prevent the UK crashing out of the EU without a deal. One is Sabine Weyand, a European Commission trade expert who is Mr Barnier’s deputy and will handle much of the detailed negotiating while he acts as the front man. The other is Alex Ellis, who has returned from being UK ambassador in Brazil to become a director general in Davis’s Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU).

Ms Weyand and Mr Ellis worked closely together on a landmark EU policy on climate change under Jose Manuel Barroso, the former European Commission president, and have remained good friends. Ms Weyand is German but studied at Cambridge University for a year. “Her loyalty will be to the EU, but she knows the UK well and her friendships will help,” said one colleague.

To Ms May’s frustration, EU leaders stuck firmly to their “no pre-negotiations” rule before the UK triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty to start the two-year exit process. But UK officials and their counterparts in European capitals have not wasted the nine months since the referendum. Despite denials, there have been secret “scoping contacts”. They have involved Oliver Robbins, permanent secretary at DExEU who also acts as Ms May’s EU “sherpa” (preparing the ground before talks). These relationships could prove vital given the tight 18-month negotiating period. The talks are due to be completed by October 2018 to give the UK and European Parliament time to approve an agreement.

The private contacts helped to avoid a major row when the UK and the EU fired their opening shots last week. There were differences over Ms May playing the security card and Spain demanding a veto on how a long-term UK-EU deal would affect Gibraltar. But they could have been much deeper.

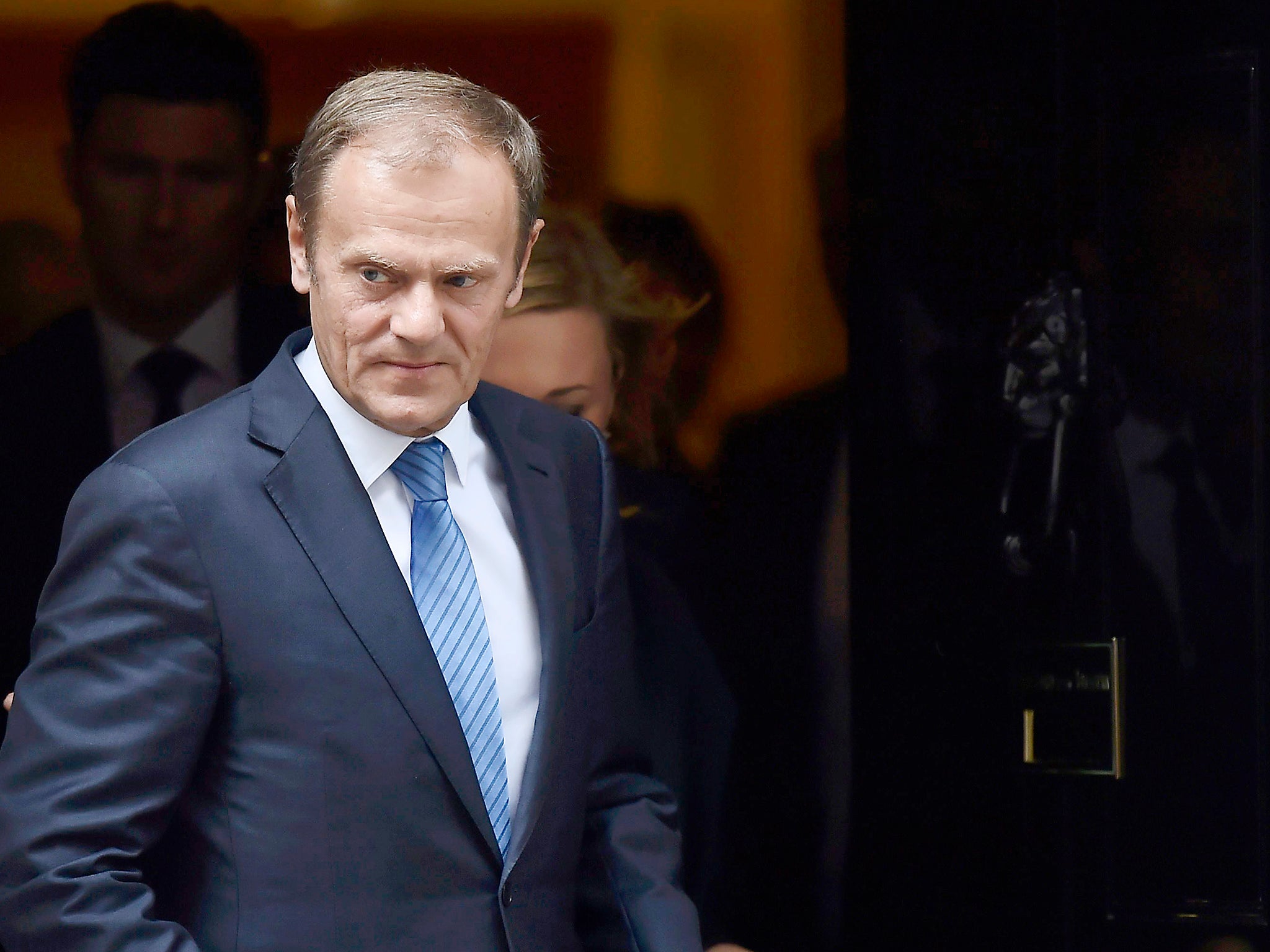

It is now clear that both sides want a deal. The Prime Minister dropped her January “no deal is better than a bad deal” mantra. That helped Donald Tusk, president of the European Council representing the 27 governments, to give a largely conciliatory response when he issued the EU’s draft negotiating guidelines.

Mr Tusk, a former Polish Prime Minister, is seen as a pragmatist, which is good news for the UK, but also as someone who will dance to the tune of Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor and most powerful player on the EU stage.

Others in the EU team may be less favourable towards the UK than Mr Tusk. Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, which is handling the talks, has little love for the UK. Martin Selmayr, his powerful German chief of staff, who will keep a very close eye on the negotiations, is even more hostile to the Brits.

One Brussels official describes him as a “super-Machiavellian figure who will put some obstacles in the road on several occasions.” He is so influential that some colleagues see him as the deal breaker or maker.Mr Selmayr is widely thought to be behind the emergence of a £50bn estimated “divorce demand” by Brussels, which could prove an early stumbling block. The actual request could be much lower, though Ms May might still have trouble selling it to hardline Brexiteers.

Mr Barnier reports to Mr Juncker, which in practise means Mr Selmayr. The former French foreign minister is seen as a bogey man by the pro-Brexit press but aides insist he is misunderstood. They say his talks timetable was not an attempt to outmanoevure the UK. He believed that dealing first with the divorce payment and the rights of the 3m EU nationals in the UK and 1m Brits in EU countries, would help rather than hinder the prospects of a long-term trade deal.

The 66-year-old Barnier is enjoying an unexpected Indian summer, and so is determined to secure a deal. But his top priority will be to keep the 27 EU governments on board: a deal must be approved by a “super qualified majority” representing 72 per cent of member states and 65 per cent of the EU’s population. Mr Barnier will regularly brief Didier Seeuws, Mr Tusk’s Brexit adviser and an old Brussels hand. So he has many masters to please, and will have less room for manoeuvre than his title suggests.

Where does the real power lie – with the Commission or the Council? There is always tension between the unelected bureaucracy and the elected leaders of national governments, and Brexit is no exception. The draft negotiating guidelines were Mr Tusk’s initiative, not the Commission’s, and will be finalised at a summit of the 27 national leaders on 29 April.

The Council intends to keep Mr Barnier on a tight leash, which is potentially good news for Ms May since the leaders may prove more flexible than the Commission. All roads lead to Ms Merkel. “When she puts her foot down, everyone else falls into line,” one Commission official conceded.

It is unlikely that the UK will be able to exploit any tensions on the EU side of the negotiating table in the Council’s new £275m Brussels HQ, dubbed the “space egg”.

Similarly, Brussels officials are fully aware that Ms May will try the “old Brits’ trick” of playing “divide and rule”. That is why Mr Tusk insisted the EU will act “as one,” meaning no side deals. In practice, bilateral discussions between the UK and the 27 will continue. Eastern European nations will be wooed, because they have many nationals in the UK and are worried about Russian aggression.

Whitehall has drawn up a list of each member state’s attacking goals (such as grabbing a bigger share of some markets) and defensive operations (such as preserving market share or needing UK co-operation on security). But with EU officials warning that such tactics could backfire, UK approaches will be kept largely under the radar.

In Brussels there is confidence that the EU can dictate terms now that Article 50 has been invoked. “Our biggest asset is the clock,” said one insider, referring to the March 2019 deadline when UK would depart with no deal if none has been reached.

The hope is that time pressure forces Britain into last-minute concessions; the EU will insist that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.” One EU diplomat said: “It is difficult to see what cards the UK has got. Theresa May tried security but no one believes the UK is going to stop co-operating on terrorism or leave Nato. Britain needs our co-operation."

While a trade deal would be in the EU’s interests, the view in Brussels is that the UK overestimates the importance of one to the bloc. The bottom line that unites all EU institutions is that the UK cannot enjoy the same or better terms than it does as an EU member.

They are prepared to take an economic hit to preserve the EU project and deter other states from leaving. An economic downside has already been factored in by the EU. As Mark Rutte, the Dutch Prime Minister, puts it privately: “This is going to be bad for both sides.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks