Brexit: What should the question for a second referendum actually be?

There are genuine problems with all the possible questions

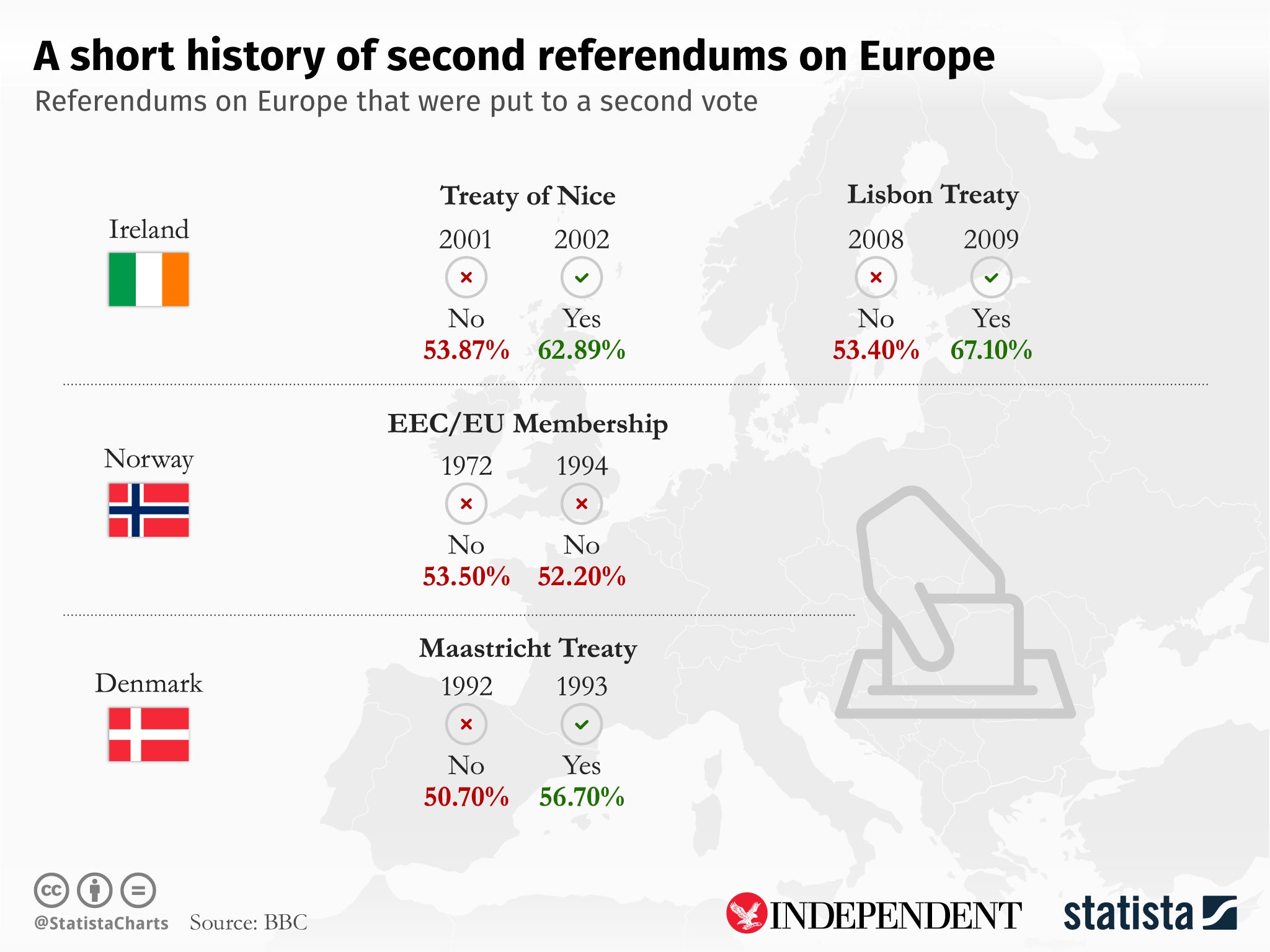

The idea of giving the public a Final Say on Brexit is gaining popular currency, with reports that allies of the prime minister are belatedly coming around to the idea of a second referendum.

But there is one problem: if a second vote is to be held, what would the question be?

This is more complicated than it sounds. There are a variety of options, but all have serious problems and would be unlikely to keep everyone happy.

Here are the main possibilities – and what’s wrong with them all.

Remain vs Leave

The most obvious option is to rerun the 2016 EU referendum question and simply ask people whether they want to remain in the European Union or leave it.

But this question repeats the same mistakes as the last vote: what does “leave” actually mean? The government is currently in deadlock and the referendum is supposed to let the people decide, but this question simply doesn’t solve the problem the government is facing. If Leave wins again, we’re back to square one. As a result, it’s unlikely to be asked.

Remain vs Theresa May’s deal vs no deal

Splitting out no deal and May’s deal seems to be a logical response to the problems with the last question. Voters would be able to choose between any of the three options.

But this would split the Leave vote, leaving Remain to almost certainly win. Most unsustainably, it could even produce a Remain win when the majority of people actually vote for Leave options. Democratically, this is a non-starter and would reasonably be seen as a stitch-up.

‘Do you approve of the Brexit deal negotiated by the government?’

The government could simply ask voters to approve or reject the Brexit deal. This suffers from similar problems as the first question: if the deal is rejected, what happens? Do we leave with no deal? Or remain?

It might prove attractive as a roll of the dice for a government trying to ram through the deal without its MPs – or then again it might not because the public would probably vote it down, according to current polls. This also has no ‘remain’ option so would surely disappoint the main people who want a second referendum – remain voters.

Two-round questions

One proposal is to ask the questions in two rounds: first, whether voters accept or reject the deal. Then, if it’s rejected, whether they want to remain or leave without a deal.

You could also ask the questions in a different order if you wanted – leave vs remain first, and then pick between no deal and Therea May’s deal if it’s a Leave vote. But whatever order you ask the questions in, there is a fundamental issue here.

Is it really a good idea to put no deal on the ballot paper, and risk giving the government an explicit binding mandate to create food and medicine shortages?

Currently, parliament can stop a no deal and credibly claim it isn’t what people voted for. But holding this referendum puts economic catastrophe back on the table and could make the situation infinitely worse – which raises the question of why you would want to hold it at all.

Polling suggests that no deal is more popular than May’s deal – it is not impossible that it could win, given voters chose Leave last time.

This no-deal problem is a thread that runs through many second referendum options. Explicitly putting it on the ballot paper is probably not a good idea. But not putting it on the ballot paper doesn’t solve the problem.

Three-way preferential voting

You could ask the three-way question and give voters the options of ranking the options, then tally them up using an alternative vote (AV). This is practically the same as two-round voting and has the same problem – no deal is on the ballot.

There are also extra problems, such as the fact that AV can produce some quite unintuitive results – and the fact that the system was explicitly rejected for parliamentary elections at a referendum in 2011, so its use would certainly be contested.

Theresa May’s deal vs Remain

This is the option favoured by the People’s Vote campaign. In some ways it is the least worst: it rules out no deal. Remainers will like it because it offers them the option of staying. It is also explicit about what each option means, so it solves the deadlock.

But it runs the risk of being seen as illegitimate: the fact remains that a not insignificant number of people are actively campaigning for leaving on World Trade Organisation terms without a deal. Many Brexiteers say they see Theresa May’s deal as “no Brexit at all”. They would consider this question a betrayal – forced to choose between two things they don’t want, despite having won the first vote.

There is also the question of political deliverability. The country has a Tory government, and if there are two things that the vast majority of Tory MPs don’t want to vote for, they are: Remain, and Theresa May’s deal. So why would they pass a referendum that forces them to choose between two options they hate?

Any question with ‘negotiate a different deal’ or ‘Norway’ as an option

The EU has said it will not renegotiate the withdrawal agreement, so putting it as an option in a referendum would be meaningless. If it was voted for the government would be stuck.

Similarly, suggestions that a soft Brexit like the Norway option (entry into the European Economic Area) or similar could be on the ballot papers misunderstand the situation. The government needs to pass the withdrawal agreement before April or extend or revoke Article 50. Having a referendum on the future relationship is fine, but it wouldn’t solve the problem and isn’t an alternative to working out what to do with the withdrawal agreement.

So in summary…

You either risk causing an economic catastrophe by putting no deal on the ballot paper, you exclude no deal as an option and risk the referendum being seen as illegitimate by the people who won last time, or you don’t solve the actual dilemma the government is currently facing.

That isn’t to take away from the compelling case for a Final Say referendum, which The Independent has campaigned for at length and collected more than a million signatures in favour of. Done right, another vote could solve the UK’s political deadlock, check whether the public still want to leave, and spell out what’s really on offer. But if one is called, the question will have to be chosen carefully, with an awareness of the tradeoffs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks