Campaign for Democracy: What can we learn from the rest of the world?

In the wake of the expenses scandal, Britain is debating how to reform politics to create a more accountable and fair system. We asked our writers around the globe to examine the relevant lessons from abroad

United States

The great virtues of America's version of democracy are its checks and balances and its direct connection with voters, qualities often conspicuous by their absence in Britain.

Britain has been described as an "elective dictatorship". In the US, Congress is a separate and equal branch of government perfectly capable of defying a president, even of the party that controls the House and Senate. Its committees in particular, backed by subpoena powers and far stronger than their counterparts at Westminster, are a check on the executive, and powerful investigative tools in their own right (Watergate being the best-known example).

Congress may share some of the clubbiness and inbred traditions of the Commons. But anyone can run for president; not just established politicians, but virtual unknowns (cf. a first-term senator named Barack Obama). Such jolts to the system are impossible in Britain, as impossible as the thought of a President being elected by his party's legislators (cf. Gordon Brown in 2007) without voters having a say.

US voters are involved in other ways their British counterparts are not. The most important difference is primary elections. Candidates are chosen not by constituency committees, but directly by party voters. This is a precious democratic safeguard in seats where the winner of the general election is a foregone conclusion. In exceptional cases, in a few states like California, voters can secure special elections to recall, i.e. dismiss, a sitting official.

But the American system has big weaknesses. It is vastly expensive – the 2008 presidential election cost $1.6bn (£1bn), and the total cost of national elections that year was close to $5bn. A US politician spends far too much of his time fundraising, and the process gives undue influence to rich lobbying and special interest groups.

Another drawback is the difficulty of changing leaders. Within a year of re-election in 2004, George Bush was desperately unpopular; the country wanted him gone. But the only means of ousting a president is impeachment. The process worked in getting rid of Richard Nixon, but turned into a partisan farce when the Republicans attempted to oust Bill Clinton in 1998 after the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

Rupert Cornwell

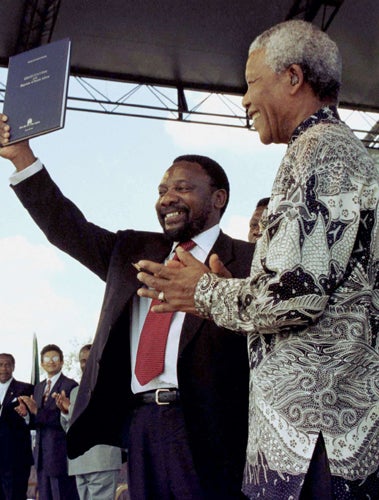

South Africa

The child of an extraordinary burst of optimism and idealism that accompanied the end of apartheid, South Africa has created a constitution that is one of the most progressive governing documents in the world.

Adopted in October 1996, it was created during inclusive negotiations that showed a remarkable awareness of the country's divisive history. The centrepiece of the constitution is a bill of rights that forbids discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, race or gender, while the "right to life" is also enshrined.

Human rights feature prominently throughout the document from the preamble which foresees "a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights".

In a reflection of its inclusiveness, the constitution also deals with the thorny issue of language, declaring 11 as official languages. It even protects the rights of foreign languages spoken among immigrant communities from German, to Greek and Urdu.

The result of all this is that all South Africans have immense pride in their system of law. The broad-based support for the constitution has meant that the accusation of riding roughshod over it has proved one of the most effective attacks during election campaigns.

The need for a written document outlining a separation of powers, independent judiciary and series of parliamentary checks and balances has been starkly apparent as South Africa's post-apartheid politics has been tumultuous. The titanic power struggle between the former president Thabo Mbeki and the current holder of the office, Jacob Zuma, was widely seen to have damaged the independence of the judiciary. Mr Zuma has publicly questioned the powers of constitutional court judges, comparing them to Gods who threaten democracy. However, the constitution has provided a rallying point for those determined not to see their democracy eroded or transformed into African politics as usual.

One thing to be said against it is that inclusiveness has overridden brevity, creating a lengthy tome in sharp contrast with a small booklet such as the frequently flourished US constitution.

Daniel Howden

Australia

The turn-out at the last Australian general election in 2007 was 95 per cent. However, it did not reflect Australians' enthusiastic political engagement so much as the fact that voting is compulsory, with those who fail to turn up at polling stations fined, albeit only $20 (£10).

Mandatory voting was introduced in Australia in 1924, prompted by a particularly low turn-out (about 59 per cent) at a federal election two years earlier. But it is not only at national polls where Australians are obliged to exercise their democratic rights: voting for state and territory governments and, in some cases, local councils is also compulsory.

Whether this enhances the democratic health of the nation is questionable. You still don't have to vote: all you have to do is turn up, have your name crossed off, then place a blank or defaced ballot paper in the box. This is known as "informal voting", and about five per cent of voters do it, although some are simply confused by the large ballot paper and mind-boggling task of listing numerous candidates in order of preference.

Some political scientists argue that compulsory voting leads to centrist (even bland) policies, because the parties focus on wooing swinging voters rather than appealing to core constituencies. Others say it favours the Australian Labor Party, since some of Labor's more traditional supporters – such as migrants and people from lower socio-economic backgrounds – might not vote were it not compulsory.

Although Australians grumble endlessly about having to vote, most accept it as a fact of life. Indeed, surveys suggest that compulsory voting is popular, with three-quarters of people supporting it. With federal elections held every three years, and numerous state and local elections in-between, voting is a commonplace activity. The most intriguing question is whether mandatory voting helps counter political apathy. As far as Australia is concerned, the answer is no.

Kathy Marks

Ireland

Despite much speculation to the contrary, neither of the major British parties has proved willing to abandon the first-past-the-post system that does so much to maintain their duopoly. But across the Irish Sea, both the political classes and the public in general are very comfortable with the Republic of Ireland's proportional representation system, which has been in use for almost a century.

Ironically, the system is, in effect, a relic of British rule, having been introduced by London to act as a safeguard for minorities.

Over the years the most common outcome of elections to the Irish parliament has been to produce coalition governments. Only twice since the 1920s has any party achieved an overall majority.

The present administration, for example, is headed by Ireland's largest party, Fianna Fail, governing with the support of the Green party and some independents.

In practice, such coalitions have often led to the instability that British critics fear. They regularly turn out to have deep divisions, which sometimes lead to their demise. At the moment the government's deep unpopularity has produced speculation that, at some stage, the Greens might pull out.

At other times, multi-party administrations have proved surprisingly stable. Bertie Ahern, who headed a number of them as leader of Fianna Fail, had a particular talent for ensuring they ran comparatively smoothly.

Fianna Fail's advantage is that it is a largely centrist but highly pragmatic party. This has made possible deals with parties of both the left and right. Such flexibility means that it has been in power for most of the Republic's existence.

David McKittrick

Germany

German voters have yet to see their MPs castigated for using taxpayers' money to buy pond ornaments, but that does not mean their politicians are any less corrupt. Angela Merkel, Germany's first woman Chancellor, got her job not least because Helmut Kohl, her conservative predecessor, was forced to step down as party leader after being involved in a political slush-fund scandal a decade ago.

That said, the Germans are proud of institutions such as their written constitution or Basic Law, and their Constitutional Court. Both were installed in West Germany after the Second World War and are seen as guarantees against a repeat of the Nazis' total abuse of power. The German electoral system of proportional representation has also enabled new parties such as the Greens to gain a place in the political spectrum.

German MPs are occasionally caught out for employing family members on expenses, but the practice is far from widespread. Political observers put this down to a tougher system of financial controls imposed on MPs by the German parliament's own administrative body.

However, Jan Techau of Germany's Council on Foreign Relations argues that while the German system of PR has allowed smaller parties such as the Greens to gain power, it does not help to get rid of sitting MPs who have lost voters' confidence. "Although they may not be first past the post during an election, they are still guaranteed their parliamentary seats by being rated high on a list system. The German method is not necessarily better than the British."

A similar view is held by Tilman Mayer, professor of politics at Bonn University: "To us, the British system is exemplary. In many ways, the 'first past the post' system is fairer and better, because it nearly always results in a clear majority. I wouldn't advocate dropping it because some MPs have misused their expenses."

Tony Paterson

France

Office and travel allowances are set at a fixed level for every deputy in the National Assembly, with no requirement to provide receipts: there is, therefore, very little to stop politicians spending the £61,000 they typically receive on top of basic pay on whatever they like. When salary and expenses are combined, French MPs receive more than £211,000 a year without any audit whatsoever.

Such generous arrangements reach their zenith in the office of the president. François Mitterrand housed a secret second family at state expense; more recently, Jacques Chirac faced corruption accusations dating back to his time as mayor of Paris, but could not be prosecuted because of his office. Nicolas Sarkozy has moved to reform the Byzantine system by which French presidents have long been paid – and in the process given himself a 150 per cent pay rise.

If the French public is relatively unruffled about such sharp practice, that may in part be because of a greater engagement in the wider political process. Turnout in general elections is relatively healthy in France, which is put down to the system whereby candidates receiving more than 15 per cent of the votes go into a second round in which the victor is finally chosen.

Since only two candidates usually make it to that final round, winners often have the stamp of legitimacy of the support of a simple majority of voters. Even when that doesn't happen, the system strengthens the chances of sensible third-party candidates to have their voices heard without risking the surge in the lunatic fringe that some forms of PR can encourage.

The practice whereby sitting deputies are also often town mayors arguably strengthens their connections with local communities, and a sense of accountability.

John Lichfield

Italy

Italy's parliament offers Britain's system a ghastly warning. If the culture of petty but pervasive corruption exposed by "Moatgate" were allowed to proceed indefinitely, this is what we could end up with: MPs chosen exclusively by party patronage and with no connection to local communities, legal immunity for those at the top, and a modest basic salary, but perks and expenses amounting to twice as much and including free train and air travel, free VIP seats at football matches and operas and much else besides.

Many Italian politicians also enjoy grace-and-favour housing around the capital. And "clientelismo" – corrupt relations between MPs and businessmen – brings bribery on a vast scale: a company created by David Mills for Silvio Berlusconi when Berlusconi was just a businessman paid Socialist Party leader Bettino Craxi bribes totalling 23bn lire (more than £10m).

As in Britain, Italian deputati belong to a self-perpetuating caste, and as in Britain, until the recent revelations were published, nobody has any detailed idea of what shenanigans they get up to.

The entrenched corruption of the caste was exposed in the early 1990s in a series of devastating bribery cases known collectively as "Tangentopoli" ("Bribesville"). Public indignation at the degree to which the politicians had their snouts in the trough led to the destruction of the Christian Democrat and Socialist parties and a rising clamour for non-professional politicians from outside the caste to take over.

Fifteen years on, the political landscape is dominated by new parties, but the changes have all been cosmetic. Italy offers a warning to those who would see in Esther Rantzen and Joanna Lumley a cure for our ills: while good and brave politicians have emerged from outside the narrow élite, most have wasted little time becoming insiders, including, of course, Mr Berlusconi himself.

Peter Popham

Scotland

It has been Scotland's fate to be treated by the English as a laboratory. Margaret Thatcher once put on her white coat and grew a petri dish culture there called the poll tax. Mind you, it didn't stop her from introducing the bacillus in England.

Then Tony Blair, denounced in some quarters as a meddling Frankenstein, completed Jim Callaghan's unfinished business of devolution. Who should emerge, blundering through the smoke after the experiment? The monster known as Alex Salmond, leader of the hated nationalists, whom devolution was supposed to drain of all life force. Now Scotland is again hailed as the test bed for a wider revolution. After the frenzy over MPs' expenses, Scottish politics offers several prototypes of reforms being urgently promoted at Westminster.

Fixed-term parliaments are the centrepiece of a people-power revolution vaguely advocated by David Cameron. It is the present reality north of the border. Salmond, the First Minister at Edinburgh, is experiencing the effect of a fixed term. He can threaten to resign, but it is hard for him to force an election as the parliament has a four-year fixed term. If he refused to serve, it would have 28 days to choose another first minister. If it were unable to, there would be an election, but the new parliament would serve only the remainder of its current four-year term.

The result, according to John Curtice, professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde, is that little legislative business is being done. The two-year-old minority Scottish National Party government is stable, "but weak in terms of the amount of legislation going through". Salmond is safe so long as the Conservatives prefer him in charge instead of Iain Gray, the Labour leader, but he cannot get much legislation through because, unless he deals with Labour, he needs at least two other parties' support.

Scotland is also a laboratory for PR, suddenly in vogue among Labour revolutionaries. It works well there. Unlike in Wales, resentment against the two-fifths of MSPs elected to "top up" party representation at a regional level is muted. But it is hardly transformative of turnout or trust in politicians.

The Scottish Parliament boasts other fashionable modernities. Committees may propose laws – as may backbenchers – and it pioneered e-petitions five years ago, before Tony Blair picked up the idea.

But what does it amount to? Cleaner government? If so, it is only in reaction to the allowances micro-scandals suffered by Henry McLeish (Lab) and David McLetchie (Tory) over the past decade. Better government? Perhaps, if less is good. But John McLaren, a Labour economist who helped draft the Scotland Act, recently said: "The policies put in place in Scotland have been different but have too often been about wanting to make Scotland stand out and wishing to be popular." On education and the health service, he wrote: "One can tentatively conclude that government being closer to the people has not led to improved relative performance in Scotland. In fact, it may have had the opposite effect."

John Rentoul

Readers' suggestions for reform

Local knowledge

Every candidate must have lived in the constituency for a minimum of five years. They will truly know it and their voters' interests. Their main home will also be clear. Every vote in the House to be a "free" vote, so members vote in accordance with their voters' wishes or interests, or their conscience, as appropriate. No member may vote after a debate unless they have been present for 90 per cent of the debate. What is the point of a debate if people vote without having heard a word of it? The debate should refine the final outcome.

Dux

Complaints panel

If my lawyer or my accountant are negligent or incompetent, I can complain to professional associations – and if upheld they can be sacked. There is no similar provision for an incompetent MP. There should be.

Anonymous

Hand back power

Power should be given back to local government. Planning enquiries by central government finish up by taking no notice of local views. Apathy follows. Do away with the House of Lords. Introduce proportional representation. Elect people to the EU Parliament who pledge to put right its failings. The EU has, in spite of its failings, been the best thing for Europeans – and that includes the UK.

Sam Deubert

Follow Ireland's lead

The single most important change would be to introduce proportional representation with the Single Transferable Vote as is used successfully in Ireland. The beauty of this system is that it gives full power to the voter instead of parties. MPs are elected for multi-member constituencies and the voter ranks candidates in order of preference, so the voter can chose between different party (or non-party) candidates and, crucially, between different candidates of the same party. In that way there can be no safe seats.

Martin Meredith

Spending curbs

Curb what parties are able to spend at elections. Most MPs owe allegiance to their party and vote the way they want them to is because the party provides the money to elect them. This would allow the MPs to vote the way they think is right for their constituents, not for the party.

revoultionnow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks